Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Araceli ArguetaMay 23, 2023

Esta entrada de blog también está disponible en español (enlace).

"Cantamos sin miedo, pedimos justicia

Gritamos por cada desaparecida

Que retumbe fuerte: nos queremos vivas

Que caiga con fuerza el feminicida” (Canciòn de Vivir Quintana)

We sing without fear, we ask for justice

We shout for each disappeared woman

Let it resound loudly: we want us alive

Let the femicide fall with force (Song by Vivir Quintana)

Whenever I listen to Quintana's Cancion Sin Miedo, I feel the urge for change. As pointed out by Marshall Ganz, narratives are the art of creating emotions that translate values into actions. When I began participating in movements in El Salvador, every march and action was accompanied by songs from Torogoces de Morazan, Violeta Parra, Residente, and many others. I noticed that the idea of another world in Latin America has always been accompanied by music and creative languages of resistance that create new meanings, make the invisible visible, and invite us to dream, fight, feel, and change.

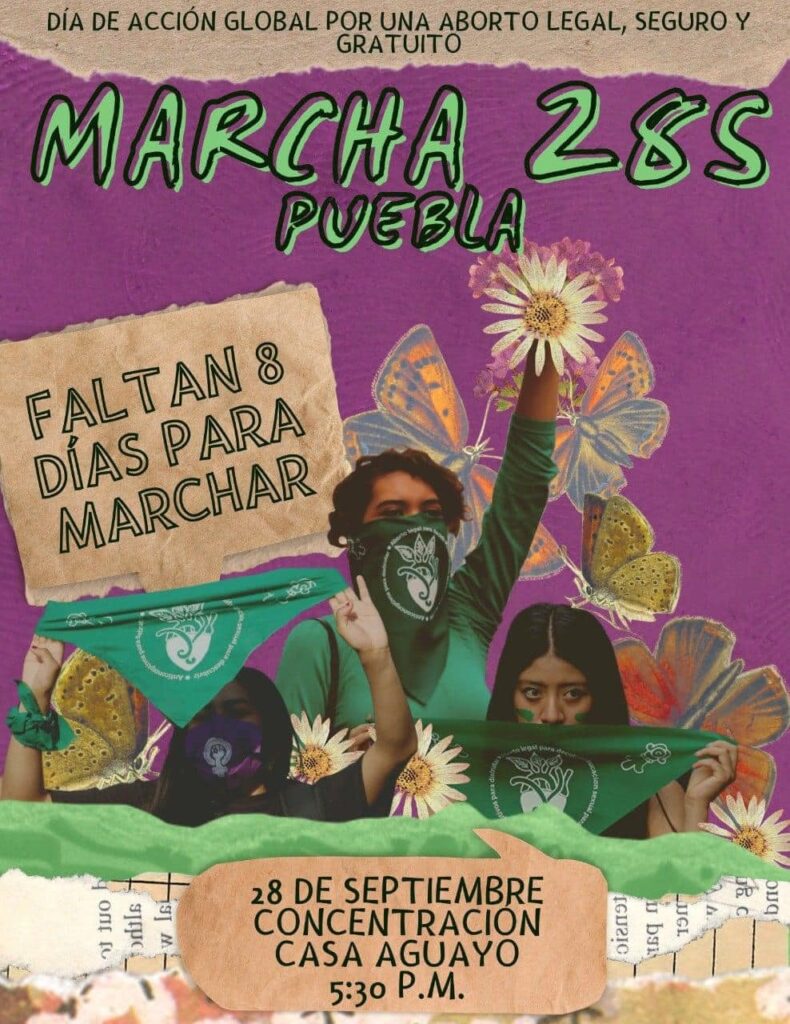

Marea Verde originated in Argentina, but new groups have emerged all over Latin America, including in Mexico (featured above). Credit: Marea Verde Mexico's Facebook page.

Between chants, green bandanas, graffiti and flags saying "Sí a la vida, no a la minería", (yes to life, no to mining), narrative resistance is built. Nonviolent movements in Latin America have a long history of using narrative resistance to mobilize people, influence public narratives and, ultimately, change policy development. Narrative resistance can be defined as a category of nonviolent actions that:

-

- Repurpose everyday objects as symbols of struggle against injustice;

- Use art (music, photography, street art, etc.) to interpret everyday life through the lens of injustice and articulate a movement's vision of tomorrow; and/or

- Reappropriate words that traditionally have a negative connotation (such as “abortion” and “Barrios”, notably through the production of music or poetry.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve begun curating a mini-series for the REACT collaboration that will explore cases of narrative resistance told by people engaged in specific movements across Latin America. This post previews some of those cases, highlighting the power of symbolism to challenge unjust systems, embody culture and history in society, and take back narratives in ways that strengthen their struggles for rights and justice.

Credit: Facebook page of Marea Verde's Mexico chapter.

Argentina and region-wide: Green Tide Power

Marea Verde ("Green Tide") is a powerful example of how symbols can create a sense of community and solidarity among diverse people who share a common goal—in a word, how symbols are vectors for unity in the face of injustice. In the wake of the Senate abortion vote in Argentina, in 2018, Marea Verde started organizing mass protests and other nonviolent actions. In an impressive display of constructive resistance, it has also created a collective that helps secure abortion access for women.

Marea Verde uses a green handkerchief as their symbol, and it has become an iconic representation of the fight for abortion rights across Latin America. The symbol of a green handkerchief was adopted because it is easily replicable and filled with cultural and historical meaning from Las Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo. Las Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo was a women’s nonviolent movement in Argentina that sought justice for families whose children were disappeared by the Jorge Rafael Videla dictatorship (1976-1983).

One impact Marea Verde’s work has had is subverting the term abortion, using it as a positive term to influence public narratives and pressure decision-makers to support better rights for women. They stopped discussing abortion as a biological life discussion and placed women's stories into it. Names, dreams and loved ones were at the center.

As we will see in a forthcoming post in this series, Marea Verde’s journey also offers important lessons about narrative production and storytelling, specifically how to frame issues for external allies and unite fragmented groups into a joint movement.

Credit: Marea Verde Mexico's Facebook page.

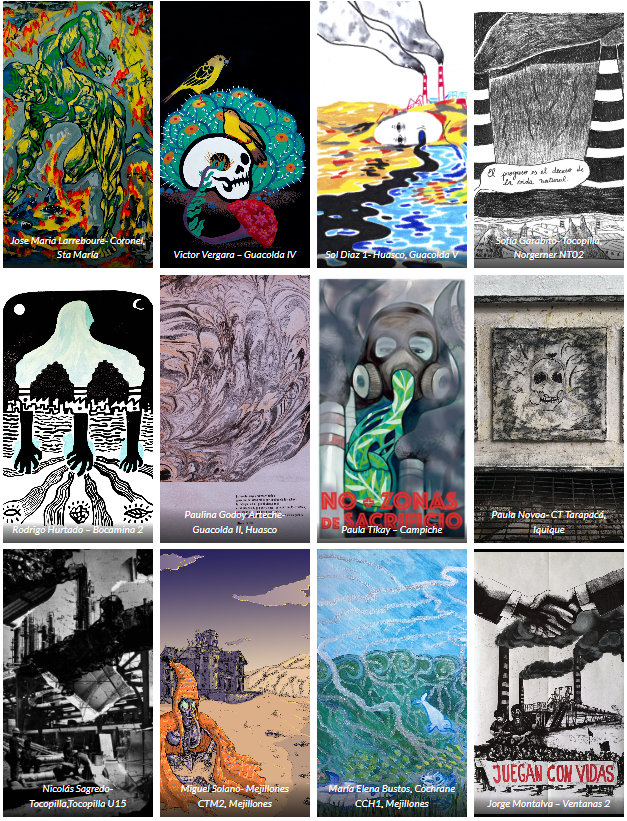

Chile: Culture at the heart of strategy

From Chile, Chao Pescao’s participation in the Chao Carbon coalition provides a compelling case study of how presenting an alternative narrative can shape public perception and influence policy outcomes. The Chilean government boasts they're the Latin American leader on climate action; the campaign underscores that Chile has established five "sacrifice zones" for waste. Communities live in those zones and are being contaminated.

The campaign started in 2018 and will run till 2030, demanding a transition to clean forms of energy and the elimination of coal-fired plants. It draws on a range of symbolic and narrative techniques to build support for political change. Of 28 coal-fired power plants, 23 are still operating in the country, so they have their work cut out for them.

They produce artistic representations of the society they live in and the effects of coal-fired plants on nearby populations. Their impact has been far-reaching; Chao Pescao has mobilized ‘unusual suspects,’ such as Borris Chamorro, a Mayor of the sacrifice zone, to their cause and even gained support from international organizations like Greenpeace.

Some of Chao Pescao's artistic representations of injustice and a vision for tomorrow. Credit: Chao Pescao's website.

Unfortunately, we won’t have the chance to hear more about Chao Pescao in this series, but you can check out their work here. They certainly deserve a mention though, because they successfully targeted big international companies with a grassroots art and narrative-based strategy, providing important learnings on the implications of target selection and sequencing of nonviolent actions against multinational corporations.

El Salvador: Hip-hop and memory

The Water Movement in El Salvador is an example of how movements can create a new narrative drawing on history and memory. This struggle uses symbols of the street and the city and notably involves hip-hop artists in producing content on water rights, as 80% of El Salvador’s territory is under water stress. It has strong participation among young people who want to break the silence about their living conditions in the “Barrios.” The music they produce (see one example here), like Marea Verde’s goals, aspires to give new meaning to the traditionally pejorative term “Barrios,” the ghetto. At the same time, a whole history of grassroots resistance creating locally based water systems came together to win the right to water in Suchitoto.

Hip-Hop en Defensa - Nam x Queen Mc - DABÚ - Ras-Hop (official video). Credit: El Lab PG YouTube.

A vision for tomorrow

Through narrative resistance, movements like these and others in the forthcoming series reappropriate everyday symbols and produce artistic representations to capture injustice, but they do not stop there. Narrative resistance is, above all, constructive resistance: it fashions new collective imaginaries–the building blocks of society–along with movements' vision for tomorrow. These groups’ transformations are local, related to specific issues and regional processes, or even individual civil resistance stories, as we will see with the forthcoming contribution of Marina, an Afro-Indigenous defender in the Isthmus (Istmo) of Tehuantepec.

Yet, what all of these movements have in common is how they challenge dominant structures and embody cultural and historical traits of the surrounding society, to take symbols and narratives back and strengthen their struggles.

Further resources

If you are interested in exploring how to apply the tactics described in this blog post, Beautiful Trouble offers a comprehensive toolbox for activists, including one-pagers and concrete examples of "Thinking narratively" and "Using your cultural assets".

Araceli Argueta

Araceli Argueta is a guest editor of the REACT series, powered by ActionAid Denmark. She is an organizer and anthropologist from El Salvador. She has organized with women, youth, and indigenous people, protecting human rights, and supporting biocultural defense. Araceli is the Advocacy and Organizing Director at the Immigrants Rights Program with the American Friends Service Committee.

Araceli Argueta es una organizadora y antropóloga de El Salvador. Ha organizado con mujeres, jóvenes y pueblos indígenas, protegiendo los derechos humanos y apoyando la defensa biocultural. Araceli es la Directora de Incidencia y Organización del Programa de Derechos de los Inmigrantes de American Friends Service Committee.

Read More