Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Maciej BartkowskiJuly 05, 2018

On the fourth of July, we in the United States of America observe the 242nd anniversary of the Declaration of Independence adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776.1 This is an opportune time to reflect on the nature and dynamics of the struggle for self-rule that our forebears waged.

The United States did not begin through the muzzle of a musket against British King George III. Our country was born through persistent nonviolent resistance of tens—if not hundreds—of thousands of residents of the American colonies. Men, women, and even children participated. Our Independence Day celebration is incomplete without recognizing the deep significance of mass collective civilian-led mobilization and nonviolent resistance campaigns between 1765-1775 that led to the de facto liberation of the American colonies before the Declaration of Independence.

Reflecting on this, Founding Father John Adams (who was also George Washington’s vice president and went on to become the second US President) stated:

"A history of military operations is not a history of the American Revolution. The revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people, and in the union of the colonies; both of which were substantially effected before hostilities commenced."

Resistance against the Stamp Act

In March 1765, the British government adopted the Stamp Act that imposed direct taxes on all legal documents and various other official papers (i.e. newspapers, and documents related to commerce) in the US colonies. The response by the colonists went beyond a simple petition to repel the act and included refusal to pay taxes, a consumer boycott, and non-importation and non-exportation of British goods.

The colonial media played an important role in defining what was regarded by the American patriots as an unjust law. Some newspapers declared they would rather cease publication than pay the stamp tax in order to continue publishing. Other newspapers continued publishing but did so illegally—using unofficial, unstamped, paper on which they paid no tax. Still others published anonymously, hiding the names of an editor or a printer. Local courts and legal professionals also joined the resistance. For example, lawyers refused to use stamps on their legal documents. This gave judges justification to close down the courts, which could not proceed legally with their work without stamped documents.

Businesses joined as well. Administrators in major colonial shipping ports refused to enact the stamps while merchants of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia made pacts of nonimportation of British goods until the tax was repealed. The intensified organized pressure by the Americans denied the vast majority of the revenue the British monarchy was expecting.

Finally, Americans engaged in a social boycott and ostracism and adopted general contempt toward those who were willing to execute the British Stamp Act on the local level. For example, in Essex, New Jersey, local residents declared they would:

“detest, abhor, and hold in utmost contempt, all and every person or persons who shall meanly accept of any employment or office relating to the said Stamp Act, or shall take any shelter or advantage from the same . . . and they will have no communication with any such persons, nor to speak to them on any occasion, unless it be to inform them of their vileness.”

By August 1765, the reports reached London that stamp officials across 13 colonies had left their posts.

Even though the Stamp Act was officially repealed in March 1766, nonviolently rebellious colonies turned it into an unenforceable law many months prior to its cancelation. This gave people a first taste of nonviolent victory, and showed they could indeed be powerful. As noted by Francis Bernard, the then-Governor of Massachusetts, people felt that “they have it in their power to choose whether they will submit to this act or not.”

Resistance against the Townshend Acts, and the American Economic Boycott

Less than a year later, the British parliament began enacted the Townshend Acts of 1767-68, which imposed duties on goods such as tea, paint, paper, and glass imported into American colonies. In response, Americans once again resorted to collective non-importation, boycotting levied imports. In addition to the formal petition, ordinary citizens led by merchants announced and joined the boycott pacts.

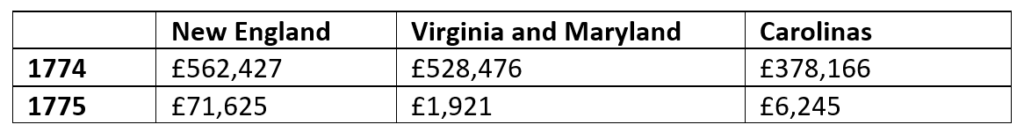

As a consequence of the colonial boycott, most of the Townshend Acts (except the duty on tea) were repealed by April 1770. Nevertheless, the campaign of non-importation, non-consumption, and nonexportation targeting the British continued. It was estimated that the nonimportation led to the collapse of British imports in 1774-75. The table below shows the impact of the economic boycott during these years:

Economic Boycotts during the US Independence Struggle and Collapse of the British Trade

Total British imports to selected American colonies between 1774-1775. See Walter H. Conser, Jr., “The United States: Reconsidering the Struggle for Independence, 1765-1775” in Maciej Bartkowski, eds., Recovering Nonviolent History: Civil Resistance in Liberation Struggles (Lynne Rienner, 2013), 300.

Creative Actions that Embodied and Popularized Nonviolent Resistance

Americans used visual symbols and vested them with deep political meaning to galvanize mobilization. One example was an elm tree in Boston, which became famously known as the Liberty Tree, under which the “Sons of Liberty” met regularly to plot resistance actions against the British.

In Wilmington, North Carolina, 500 residents joined a political theater in the form of a mock funeral where they paraded an effigy of Liberty and afterwards placed it into a coffin. Before the coffin was buried, the pulse of Liberty was checked, and people discovered she was still alive. The local newspaper reported that people “concluded the evening with great rejoicings, on finding that Liberty still had an existence in the colonies.”

Spearheaded by women, fashioning and wearing homespun clothes spread across the colonies. “Daughters of Liberty”, as they were known, promoted economic self-reliance by spinning clothes for themselves and others in public spaces such as churches while drinking “liberty tea” from raspberry leaves, basil, and mint. At the same time, they supported and motivated others to participate in the total boycott of the British goods.

Building Parallel Institutions

A critically important resistance activity between 1770 and 1774 involved building alternative political and economic institutions as a powerful instrument of nonviolent conflict. This form of resistance entailed creating new organizations and institutions that replaced the functions of “official” institutions of the British crown widely regarded by the local population as illegitimate.

By 1773, numerous Committees of Correspondence to coordinate actions between the colonies sprung out. In response to a famous disobedience act of dumping imported tea into Boston harbor, the British introduced the Coercive Acts in 1774 to punish the people of Massachusetts and set an example for other colonies about the costs of disobedience. However, this British repression backfired, and prompted colonies to issue a call for intercolonial unity and the establishment of an intercolonial congress. Every colony except Georgia elected their delegates to the new congress, and the First Continental Congress—an excellent example of an extra-institutional parallel governing body—met in Philadelphia between September 5 and October 22, 1774. It adopted the Continental Association to implement total non-importation of British goods until colonial grievances were addressed. Non-exportation of tobacco, lumber, and other raw materials would follow in the event of British intransigence—a powerful noncooperation weapon clearly designed to escalate the nonviolent conflict if needed.

Between 1774 and 1775, numerous extralegal congresses on local, county, and provincial levels across the colonies were set up to enforce the Continental Association provisions. The British considered them illegal but these local councils often assumed de facto legislative and judicial powers to enforce Continental Congress decisions.

Thus, the established parallel institutions built self-reliance, enabled self-governance, and created networks through which the colonial resistance could coordinate, expand solidarity, instill unity across colonies and reinforce common identity among their residents. This was the last straw for the British. These entities revealed strikingly what the British official rule over the American colonies had become: an empty shell of formal titles and imperial institutions, without any governance substance—or obedience of the people, for that matter.

The Nonviolent Stance and Violence in the Struggle for American Independence

The British responded with a level of violence that was hardly sufficient or effective at halting what has been put in motion by a decade of nonviolent resistance. The American colonies’ Declaration of Independence formally recognized what nonviolent civil resistance had already achieved by then: colonists’ own self-rule, forged through years of civilian-led organizing.

Throughout the civil resistance years, nonviolent discipline among the colonists remained relatively strong despite sporadic acts of violence. Anecdotal evidence suggested that a nonviolent approach to challenging the British was seen as strategic and effective. Defending a British loyalist from violence at the hands of Boston protesters, the Sons of Liberty in 1769 shouted, “No violence, or you’ll hurt the cause.” Samuel Adams, seen as an advocate of violent resistance, in 1774 warned, “Nothing can ruin us but our violence.”

The ensuing war of independence from 1775 to 1783, seen by colonists as a necessary response to the British military campaign, exposed internal divisions. The rate of desertion from the colonial army was estimated at around 20% while, according to Robert Calhoon, more than half of colonists with European ancestry avoided involvement in violence altogether or sided with the British.

The turn to arms shut out women and others in American society, limiting participation in resistance to predominantly fit adult men. Any sympathizers of the American colonies from within British society were also quick to abandon their views for fear of reprisal for sedition in times of war. In contrast to civil resistance, which had resulted in no known deaths, war led to 4,500 American military casualties (excluding civilians). As historian Walter J. Conser noted, the war achieved little that had not already been gained by civil resistance.

What would have happened if the colonists had not responded with violence? The worst-case scenario, in which the British would have nothing to shoot at, would have been a protracted British occupation of the colonies. But even then, the occupation would have become extremely costly and impossible in the long run.

A Civic Republic in the Making

After the Declaration of Independence and the end of armed hostilities, a new Republic emerged, full of fundamental democratic flaws. Deep injustice continued as the Black population lived in slavery; Native Americans had land stolen and were killed in large numbers; women did not have equal rights to men. Yet, the Constitutional system of the United States had broken from monarchy, and reflected a distinct opening toward a more democratic political system, with promise that it could be improved by future generations.

Over the centuries, we have achieved incredible wins for women’s rights, minority rights, and so many other rights and liberties, primarily during periods of popular nonviolent resistance campaigns.

On the fourth of July, we celebrate the birth of our nation. That birth came about through struggle, and much of the power in that struggle was harnessed and exercised by popular nonviolent resistance against unjust laws and practices. This was essential to the establishment of our Republic, and has been crucial to its well-being ever since. We must never give up on it.

The content of this blog post relies on and is informed by the chapter in my edited book, Recovering Nonviolent History: Civil Resistance in Liberation Struggles, “The United States: Reconsidering the Struggle for Independence, 1765-1775”, written by Walter H. Conser, Jr. The chapter is freely downloadable online.

Maciej Bartkowski

Dr. Maciej Bartkowski is a Senior Advisor to ICNC. He works on academic programs to support teaching, research and study on civil resistance. He is a series editor of the ICNC Monographs and ICNC Special Reports, and book editor of Recovering Nonviolent History. You can follow him @macbartkow