Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Amber FrenchJuly 27, 2023

Mohsen Sazegara has been a social media influencer since before it became a thing.

Having started his YouTube channel in June 2009 to share knowledge and resources on nonviolent action in Farsi, he pre-dates nearly every pioneer of the influencer phenomenon. But Mohsen's influence has nothing to do with the fashion or fitness industries. The only "brand" he represents is nonviolent revolution for rights, freedom and democracy.

Credit: Mohsen Sazegara's Facebook page.

Since 2009, Mohsen Sazegara—an Iranian mechanical engineer by trade, ex-regime politician, and now prominent journalist, dissident and activist educator—has regularly broadcast videos in Farsi, each of 10 to 15 minutes in length. The videos each propose a news round-up about Iran, as well as a mini-lesson about the dynamics of strategic nonviolent resistance. At over 4,300 videos today, he broadcasts these videos via YouTube (27,500 followers), Facebook (189,000 followers), Twitter (20,900 followers) and Telegram from his home studio in Virginia (USA), where he lives in exile.

As a politically engaged “influencer”—though at the age of 68, he absolutely does not consider himself as such—, he engages in a form of mass education for activists in Iran.

I had the chance to catch up with Mohsen virtually last month. As a result of his activist education work, he has become a major diaspora actor in Iran’s nonviolent movement for human rights, democracy and secularism. Having last interviewed him in August 2017 and again in December 2019, I wanted to ask him about the evolution of the movement since Mahsa Amini, a young Iranian woman, died last September while being held in custody by the “morality police” for allegedly breaking the hijab dress code for women. I was also curious to probe further into how Mohsen’s work has evolved since this tragedy unfolded and triggered another mass uprising in his origin country.

An unexpected turn in early career trajectory

Mohsen has been in politics since the age of 16. He was one of the founders of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the main repression mechanism of the Islamic regime. For a decade, he was the Deputy Prime Minister and then head of the biggest industrial complex of Iran, among other top positions in the country’s politics.

Mohsen Sazegara supported the establishment of the Islamic Republic back then. He later turned against the Islamic Republic and has been one of Iran’s leading dissidents ever since. His regular webcasts have bypassed Iran’s censors and firewall and served to educate hundreds of thousands of people on the use of nonviolent civil resistance to achieve democracy and human rights.

1979 Iranian Women Day protests the compulsory hijab. Credit: Mohammad Sayyad (public domain, unedited).

His crossover didn’t happen easily. “Changes like that don’t happen spontaneously when you believe something for 30 years of your life”, he tells me. In the 1980s, the Iran-Iraq war broke out, and he found out about brutality and prison torture at the hands of the Islamic regime. He had a gut feeling that “something was wrong.”

In 1986, he resigned from his position as Vice Minister for IT affairs. He had more time on his hands, so he started to re-read books and articles of the founders of the Islamic Revolution, including Khomeini himself. He had read them when he was in his 20s, but at the time of re-reading them, he was 32 or 33 years old. He was no longer an overexcited young adult, to use his own words.

What he found was that what was happening in Iranian society—the succession of uprisings, many of which were nonviolent—was not accidental. It was "essential". He found out that other countries had similar historical trajectories—moving from theories of maximal religious ideology to secular democratic government.

In 1989, he resigned from the government completely and started to write for magazines and newspapers. They were all shut down by the regime and he was imprisoned four times by the Islamic Republic. He went to universities to teach this knowledge to younger generations. His field of study was mechanical engineering, but by then he had become well-versed in history and political science.

Revolution vs. evolution

His first actions as a dissident were to try to reform the regime. “We were defeated, it didn’t succeed. We were banned by the second ruler after Khomeini,” Mohsen says. Gradually he became more active in opposing the regime. He went on hunger strike during his final imprisonment in June 2003, when 800 students at 50 different universities in Iran had been arrested alongside him for dissident activities. The student movement, along with his son who was a student at the University of Iran at the time, found itself behind bars.

Mohsen met Peter Ackerman, founding chair of ICNC and civil resistance scholar, during a trip to London in 2004. He had traveled there for a medical operation—a safe pretext for him to leave Iran. A few months later, in 2005, he travelled to the United States for the first time and participated in an ICNC educational workshop for activists. The workshop participants were “all studying and practicing nonviolent tactics to think about strategic planning of nonviolent movements”, he recalls during our interview. “All together, gradually I converted into what I’m doing today to educate this generation.”

A paradigm shift

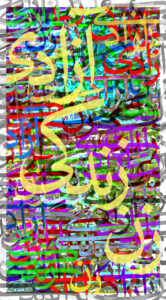

Click to enlarge. "Woman, life, freedom", typography of the main slogan of the 2022 protesters following Mahsa Amini's wrongful death under police custody. Credit: Farzan44 (CC BY-SA 4.0, unedited).

Over the course of Mohsen’s career, Iran has seen its share of trigger events like Mahsa’s death, but these events are never spontaneous, he tells me. They are rooted in decades of nonviolent organizing in Iran against the Islamic Republic.

“If I define a revolution as when distant groups within a society who have been marginalized from politics and social affairs come to the scene together and demand to remove the ruling class and the rulers, then… this is a revolution”, he says. Revolutions can be violent or nonviolent, can succeed very quickly or slowly, but revolutions don’t happen by the will of one person or one group. It’s an important social affair that shapes gradually over the years.

Iran has seen a paradigm shift from a revolutionary ideological version of Islam to one of human rights, democracy and secularism. “Sometimes I say people my age are lucky because we’ve seen two paradigms. Every intellectual and activist in Iran today produces in the latter paradigm”, he assures me.

The young generation was born under this new paradigm. They have a different lifestyle than the regime, which tries to impose a certain lifestyle on Iranians, what they wear, what they read. Today’s revolt against the regime naturally sees a distinction between the regime’s lifestyle and their own.

Mohsen, a natural-born educator with a penchant for history, gives me the full background of why Iran is different today, a convergence of factors ranging from urbanism and the decline of communism to advancements in communications technology.

But the development that stuck out for me was the cyclical effect that growing literacy and college education rates put into motion in Iran: “When more women come to the political and social scene, it changes relationships within the family, and that, in turn, serves as a model for gender relationships in other aspects of society. Women are at the center of the struggle fighting for people’s rights”, Mohsen pinpoints, promptly bringing the conversation right back to its point of departure.

Impacts of civil resistance mass education

Police during the 2017–18 Iranian protests against a hike in gas prices. Credit: Fars Media Corporation (CC BY 4.0, unedited).

Since the uprising in 2019, triggered by a hike in gas prices and brutally repressed, many young people have been exposed to civil resistance via Mohsen’s YouTube channel. Mohsen recorded the use of more than 50 new tactics that have been used in Iran (knowing of my involvement in the early stages of the publication, he assures me that he had sent his list of tactics to Michael Beer, the author of Civil Resistance Tactics in the 21st Century, ICNC Press, 2021).

What’s new on the innovation frontier in Iran? Activists plan decentralized tactics and organize in individual neighborhoods before coming together physically, for example. This hybrid dispersed/concentrated approach to organizing has the advantage of stretching forces of repression thin. The regime used to successfully repress any protest in the space of about four of five days, but young activists’ innovation is helping their actions continue for more than 100 days.

Mohsen noticed big differences in terms of his audience in the weeks that followed Mahsa’s wrongful death. “News got hot and the movement rose up”, he comments. His videos usually amass around 20,000 views, but that figure jumped to above 68,000 the day after the news of Mahsa’s death broke. He also received a significant number of messages via his various accounts, asking for him to share more books, articles and other training resources in nonviolent civil resistance. The video he shared on November 16, 2022 even amassed 230,000 views, when the Iranian regime announced that Ali Khamenei, the leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran since 1988, was replaced for security reasons. The regime feared that the Iranian people would attack his palace and to try to take him hostage.

"Change is on its way"

As our conversation shifts to prospects for change in Iran, Mohsen’s tone becomes a shade more serious: “There are some dangerous alternatives to a peaceful transition, like if we were to have a civil war in Iran. Or a failed state for some time and every type of dangerous animal in the swamp comes out, like what happened in other countries in that region. Or we may have a military coup and military dictatorship. And when that comes down, Islamists take over again.”

In evoking these possible paths, Mohsen, true to form, was sending a message to the few groups in Iran who do not embrace nonviolent resistance as an effective political strategy for change. Mohsen reiterates that what is happening is deeply rooted and change is on its way in Iran. How the movement manages the transition “may well rest on doing everything we can to avoid these less peaceful alternatives.” He says that most Iranians believe in nonviolent civil resistance as the only hopeful path.

It's a summer of preparation for the movement, but for the regime as well. Mohsen seemed sure of this. For its part, the movement is considering big strategy questions of how to usher in transition peacefully but also planning campaigns to unite disparate groups in Iranian society under the secular democracy cause.

As for the regime, it is innovating how it does repression to curb this innovative and under-the-radar organizing. The regime has had to rebuild because “it got damaged too”, explains Mohsen, referring to the fallout after the repression of the 2019 uprising and the ongoing uprising since Mahsa's death. Very deep cracks happened within the regime, and the repression machine, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, is having to rebuild and train new teams.

What will follow this "summer of preparation" for both sides? Mohsen hesitates before he shares his conjecture, nourished by five decades of political engagement, revolutions and a paradigm shift:

“This fall, we will wait and see what happens. Maybe there will be a showdown... a new stage in the revolution.”

Amber French

Amber French is Senior Editorial Advisor at ICNC, Managing Editor of the Minds of the Movement blog (est. June 2017) and Project Co-Lead of REACT (Research-in-Action) focusing on the power of activist writing. Currently based in Paris, France, she continues to develop thought leadership on civil resistance in French.

Read More