Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Liza López and Eduardo BurgerApril 20, 2018

In early May 2017, in a small bookstore in Caracas, people from all walks of life and ages gathered to talk about protesting the Venezuelan government’s undemocratic and oppressive policies and actions. Outside the store’s large rectangular window, in the middle of the street, a few meters from Plaza Altamira, youngsters wearing t-shirt masks began pleading for money and food, also in the name of the resistance movement.

Both parties—inside and outside of the bookstore—were in the midst of what would become a four-month cycle of protest, from April to July last year, in which nonviolent and violent actions shook the city.

During this time, the masked youngsters, nicknamed “escuderos” (squires), showed up week after week around barricades, on the highways, at the edge of police picket lines—an auxiliary corps to those nonviolently marching against Venezuelan government officials kidnapping human rights and democracy.

Yet not all escuderos demonstrated commitment to nonviolent discipline: some of them engaged in, were complacent to, or promoted violent actions. And this is why many people coalesced around the bookstore group to found the Civic Laboratory for Active Nonviolence—a space in which they could express their rejection to the government, not through violence and destruction but through creative, innovative, nonviolent civil resistance.

Piloneras (@Piloneras) singing at the Los Palos Grandes Market in February 2018. They engaged in a symbolic act of respect to clean the Venezuelan flag in the Los Palos Grandes square fountain. Source: Authors.

The “Labo”: Daily Operation, Challenges

Without a meeting place of its own, the Civic Laboratory (or the “Labo”, as we call it) and its many volunteers moved from street plazas to basements in cultural centers to co-working spaces in office buildings. Communicating via email and WhatsApp, they gathered on a weekly basis, but acted upon their ideas almost daily.

Due to its mix of business start-up spirit, street actions, technology, and the arts, the Labo became a factory of newborn ideas and initiatives. People felt at ease with its diversity and horizontality, as well as its fresh and innovative approach to nonviolent action against undemocratic rule. Throughout the 2017 protest cycle, volunteers designed prototypes for actions that were tested, tweaked, and re-tested. Consultations with specialists from various fields and a steady stream of newcomers allowed innovation to flourish.

In its first year, the Labo experienced some setbacks. Early on, it tried to replicate its initiative in a nearby borough but failed to help residents there close the gap between emotional engagement and effective nonviolent resistance methods.

The Labo also did not manage to create a constructive link with the escuderos whom the Labo wished to influence through nonviolent doctrine and strategies. By July 2017, the youngsters found themselves at a dead end when waves of repression grew and violence from both sides of the picket-line ensued. Spoilers in street actions were unarmed or poorly armed with homemade masks, shields, and molotov cocktails, fighting against a police force heavily equipped with firearms to repress protests. Many protesters were still killed or seriously wounded that month. Infiltrators in the groups of escuderos were identified. All of this made it very difficult for the escuderos to struggle effectively and maintain unity.

Also, by end of that month, the right to protest was partially suspended. The Labo, for its part, struggled to recruit new participants. By August, massive protests had died down.

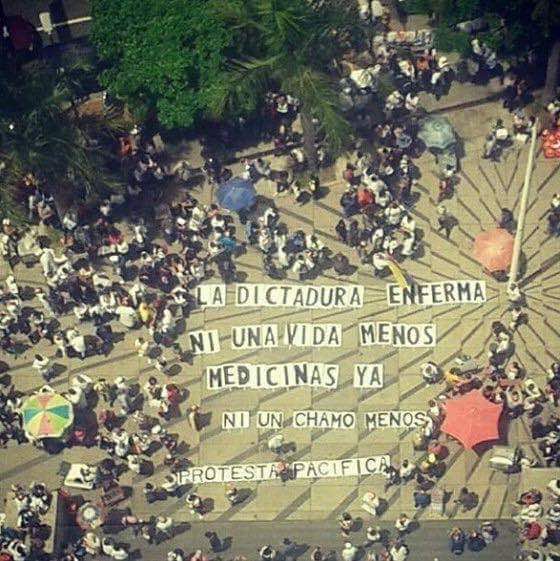

In the midst of these challenges, the Labo did manage to help organize a Peaceful Protest Alliance to march in tribute to the victims of repression since 2014. It was one of the few great protests summoned by nonviolent action groups rather than opposition political parties.

Protesters prepare to march with Dale Letra (@Dale_Letra) letters, making up the phrase "Democracia Ya" (Democracy Now) and En Protesta Pacífica (In Peaceful Protest). Source: @Dale_Letra/Twitter.

Nonviolent Methods and Tactical Innovation

Despite the setbacks, the Labo has continued growing, in large part thanks to its tactical innovation and commitment to nonviolent discipline. Another key element has been the emergence of the Labo as a meeting place where a wide range of people, organizations, and initiatives have connected and enhanced their networks.

One example of nonviolent methods to which the Labo has contributed is called Piloneras, in which women sing traditional Venezuelan songs and play instruments made with recycled materials. Months after Piloneras began, some 15 volunteers involved remain active today.

Another example is called Dale Letra, which balances its rebellious, almost aggressive chants with respectful and thoughtful language. Dale Letra also developed a mobile alphabet that allows citizens to recognize each other and carry giant posters together through the streets of Caracas. Dale Letra’s social media accounts have more than 8,000 followers today.

Source: @Dale_Letra/Twitter.

A third example of innovative actions linked to the Labo is El Bus TV. This newscasting vehicle is designed to disrupt government censorship by keeping passengers on public transportation up-to-date on news about protests and what is happening in their neighborhoods. Thanks to passenger feedback, El Bus TV has evolved into a small business centered in developing live, face-to-face newscasts in public transportation systems across the country.

El Bus TV (@elbusTV) requires only two people to function: a journalist to announce the news in a professional yet attention-grabbing way, and someone to handle the logistics (like holding the handmade "TV"). Source: @elbusTV/Twitter.

These actions have helped the Labo understand that if repression succeeds by treating people like mere objects, then it is critical to design actions where participants preserve their individuality and capability of interacting as human beings—not as mere numbers in a street action.

Different Paths, Different Fates?

Almost one year after the protest cycle, some escuderos have created a political movement after having disbanded. Yet political parties are struggling to keep their grip on the increasingly dire political, social, and economic situation of the country. Small protests take place here and there amid spreading hunger, deprivation, and displacement.

The Labo, for its part, continues to design new methods of nonviolent action, building on lessons learned. It now knows, better than ever, that in a country where oppression thrives on humanitarian emergency, civic protest must remain in permanent innovation mode to achieve sustainability and solidarity.

This is why it has decided to focus on connection, organization, and the development of a constructive vision of the future, transforming what began as a space for discussing nonviolent tactics, into a citizen hub centered on enabling solutions—and putting forth new questions—in our humble yet innovative search for democracy.

This article received further editing to clarify authorship of the initiatives described in the article. The Labo does not claim the authorship of the initiatives to which it contributes.

Liza López

Liza López is a seasoned Venezuelan journalist and media coordinator for Venezuelan newspapers El Universal, El Nacional, and Últimas Noticias. She is also Director and Editor in Chief of Marcapasos, a chronicles magazine that she founded 10 years ago, which focuses on ordinary peoples’ stories that are little explored in the mainstream media.

Read MoreEduardo Burger

Eduardo Burger is a long-time screenwriter and dramatic arts teacher. He creates educational projects and develops media content on human rights, mostly through community engagement, visual arts workshops, and other innovative approaches.

Read More