Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Deborah MathisJanuary 15, 2018

Note: This article refers to an in-depth video interview that the author conducted with the Rev. Dr. James Lawson, which will be released soon exclusively on Minds of the Movement.

There was a time when his name was tied to the headlines. Now, you have to burrow through the history books to find it. Just as well. It was always the mission, never the fame that drove Rev. James Lawson.

The Rev. Dr. James Lawson during the 2016 ICNC Summer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts. Source: ICNC.

It’s why he was more than content to work behind the scenes with Martin Luther King, Jr. in the heyday of the Civil Rights Movement. From the 1950s on, James Lawson taught the principles and strategies of nonviolent civil resistance to hundreds of people at the request of Dr. King. Some of these people went on to lead the Nashville lunch-counter sit-ins in 1960, to form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and to complete the Freedom Rides at a time when the risk of violence nearly brought them to a halt. King went on to refer to Lawson as “the mind of the movement” and “the greatest teacher of nonviolence in America.”

Even so, addressing the Reverend Dr. James Lawson as a civil rights “legend” or “icon,” as I did when I interviewed him in October, leaves you feeling a little silly and superficial afterward, despite the attempt at deference. Lawson is too serious-minded for such flattery. He brushes it off and turns the conversation to the work—not only that which has been done but also that which remains.

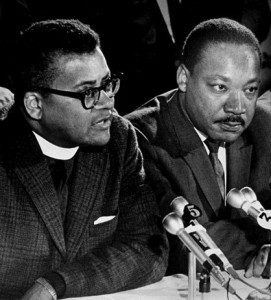

Lawson alongside King at a Memphis press conference in March 1968. Archival image.

“Too much activism in the United States is ... focused on how you bring about dismantling of the old stuff so that you can make real space for the new access, the new present moment,” he said when we met in Los Angeles, occasioned by the revival of the James Lawson Institute for movement leaders and organizers. “We have to have some people who get a grasp and get a picture of some of the strategies that people have used in campaigns of civil resistance. And then … update or reapply it.”

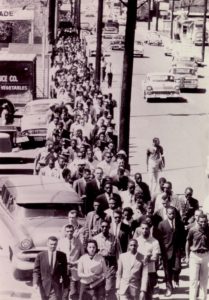

Click to expand. African-Americans and others protesting segregation march to Nashville City Hall to confront the mayor, Tennessee, USA, 1960. Archival image.

A case in point: During the student sit-ins that led to the desegregation of Nashville’s lunch counters in 1960, Lawson prescribed a tactic to confound the opposition. As one group would sit at the counter only to be arrested, another set of activists would move in, take their seats and get hauled off to jail, followed by the next group. The ongoing waves of demonstrators exhausted and overwhelmed authorities and their resources. Moreover, it signaled that the activists were organized, unbowed by fear, immovably determined—and could overwhelm the opposition’s endurance and capacity. And that’s how a system crumbles.

For all its brilliance and effectiveness, the method was a borrowed gem, Lawson said. He had learned the tactic from Mahatma Gandhi’s historic march on the Dharasana saltworks in 1930, whereby rows of volunteers would step forth and approach armed guards, who beat them mercilessly.

“Volunteers would go up to the gate and remove the bodies and the injured people,” Lawson explained. “They would clear them away from the gate and then the next 200 would come forward and systematically march up to the gate. I remembered that from my reading and said, ‘Well, that’s the strategy for this’” (watch the short video segment below, taken from ICNC's forthcoming interview with Lawson).

Over the years, Lawson has amassed a treasury of nonviolent civil resistance methodologies, which, ever the teacher, he is eager to share, provided the listener appreciates the value of know-how. After all, he says, it takes more than a riled up spirit to build and sustain a movement; it takes study and planning too.

“Every student that’s going to become a doctor is going to be taught and trained through patient care at a university hospital the last two years,” he noted. “Well, if medicine requires that, why isn’t that a model for what’s required for other kinds of human endeavors for hope and change and for carrying out the noblest sides of our humanity?”

Accordingly, Lawson still sponges up new ideas while delighting in the increasing popularity of civil resistance scholarship and study. Because the field is evolving, he says, continuing education is fundamental to serious activism.

So, what do you call a man who has studied with Gandhi’s disciples, walked with Martin Luther King, Jr., and helped mentor a movement?

If you want to honor him, you go with the label he prefers—the one he gives himself.

You call him a “learner.”

Featured image: College students sit in at a downtown lunch counter to defy racial segregation, Nashville, Tennessee, 1960. Archival image.

Deborah Mathis

Deborah Mathis is a senior journalist. Previously as ICNC’s Director of Communications, Deborah developed, executed and coordinated ICNC’s communications, marketing, and media relations, working in collaboration with the organization’s staff and advisors. She helped develop the Minds of the Movement blog and served as co-editor.

Read More