Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Amber French-GrietteFebruary 18, 2026

“Former members of the resistance asked him, ‘How did you know what we were doing, all those tricks we played on the Germans? We thought that it all was secret.’ Steinbeck’s reply was, “I guessed. I put myself in your place and thought what I would do.”

Alain Refalo shows us how two decades before strategic nonviolent conflict became an academic discipline, American literary figure John Steinbeck and Vercors penned human-sized fables about dignity and the collective power which derives from people’s desire to remain free. A close reading of Steinbeck's The Moon is Down 84 years after its publication reveals many hard lessons for everyone—from the defense establishment to pacifists and humanitarian actors.

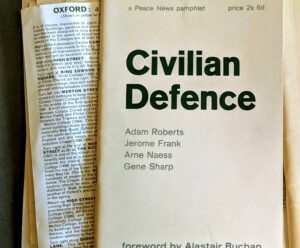

A 1964 conference was a thought experiment in developing civilian resistance as a national defense policy. World War II was fresh in the minds of its participants. Credit: Author (Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, King's College London).

The Moon is Down (1942) examines the human experience of occupation, focusing on both the occupied population and the invaders. The story set the stage for theorizing unarmed resistance two decades later, when those of age during World War II had had some distance from the experience of war.

Steinbeck began writing this novel in the last months of 1941, and it was published in March 1942, just three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He recounts the occupation of a fictional country resembling Norway. The population discovers within themselves "the greatest strength of a democracy: the strength of free individuals united under leaders […] who are merely upholders of common values”, writes Donald V. Coers in John Steinbeck Goes to War: The Moon Is Down as Propaganda (1991).

American literary critics, inexperienced with occupation, decried the book as naïve and demoralizing. History later confirmed the accuracy of Steinbeck's views on human behavior in such a context. Also confirmed was his idea to inspire through affirming and reflecting back Europeans’ real experiences under occupation: this is coherent with Jacques Semelin’s theory about resistance and East-West-East communication in Freedom Over the Airwaves. Machiavelli himself even would have approved of Steinbeck’s story, having noted that democracies are very difficult to conquer. Numerous post-war testimonies of retired German soldiers corroborate that unarmed resistance was a greater challenge for occupying forces than armed resistance.

How could an American novelist have understood occupation on such an intimate level without ever having set foot in 1940s Europe? And why does any of this matter in Europe’s security context today? This article seeks to shed light on these questions, drawing on participatory research, in-depth interviews, and archival research conducted from March 2025 to February 2026, and distilling important lessons for key European actors all along the armed/unarmed spectrum.

The human experience of occupation

Adam Roberts organized a conference on "Civilian Defence" at St. Hilda's college in 1964. Audio tapes of the proceedings reveal a scenario-building exercise led by Don Goodspeed exploring the "purely hypothetical case" of a large eastern European country (Blueland) being invaded and occupied by the Soviet Union (Redland). "There is a foretaste here of later events in Czechoslovakia, Poland & Ukraine", Prof. Adam Roberts affirms.

Writing as Nazi occupation was unfolding across Europe, Steinbeck was reflecting in real-time on a resistance that did not involve battlefield scenes. Instead, it involved daily micro-interactions between individuals in the occupied/occupier nexus. Far from good guy/bad guy dichotomies, villager women were sometimes prone to violence, while invaders’ evil deeds ultimately cost them their social acceptance, recreation, carnal desire, and other basic human needs. “People, for the most part, are the same wherever they live”, Steinbeck stated bluntly in a post-war interview.

The Moon is Down spread like wildfire across occupied countries, fueled by spontaneous clandestine translation, printing, and distribution. Steinbeck, who had many European friends, somehow sensed deeply how the populations felt about living under the Nazi heel—or perhaps it was just the novelty of getting that granular about something so macro like war.

"I needed the feeling that we tried to do something"

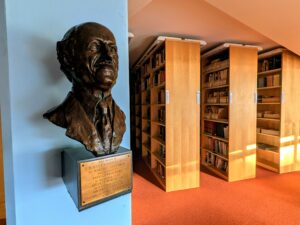

Adam Roberts, Emeritus Professor at Balliol College (UK), shows me names of fallen soldiers from World War II who had had an affiliation with Balliol. Credit: Author.

Steinbeck conceived of his tale while working for US governmental agencies specializing in wartime information and intelligence. He came into contact with resistance members who had escaped occupation, making friends with Norwegians, Danish, French, and Dutch people. “Our resistance was not so very important, but it was a good thing that it existed. We needed it, and I needed the feeling that something was… well, that we tried to do something, and I always said, if only you pick into [the Nazis] with pins, [even that] has its effect,” one such escapee told Steinbeck.

Steinbeck also came into contact with William J. Donovan, the “father of American intelligence”, who would go on to found the Central Intelligence Agency. Donovan was known for surrounding himself with artists and literary figures to help outside-the-box thinking on how to boost the morale of anti-Nazi resistance movements. Together they conceived of the idea of a propaganda novel to inspire and validate the underground resistance.

A bust of British Captain Basil Liddell Hart (1895-1970) sits in King's College military archives. Correspondence and writings of Liddell Hart, a highly respected military strategist who experienced World War II, reveal an astute scholar and advocate of unarmed resistance in defense policy. Credit: Author.

Within months of its release, The Moon is Down became popular in Europe, particularly in occupied countries, it was later proven. People took it upon themselves to translate their own versions, sometimes resulting in multiple language translations popping up simultaneously. Underground printing and distribution went unnoticed by German soldiers for some time. In Denmark, soldiers even unknowingly helped transport the book before later realizing its contents and getting the book banished. The novel spread across Europe, resulting in some 30 editions published during the war. Copies were eventually found in many areas of China and Russia. In total, more than 210 editions have been published to date.

Testimonies from resistance members, collected by Donald V. Coers in the 1980s, showed how Steinbeck validated people’s experiences and instilled hope instead of using fear or stereotypes.

Modern victory and defeat

The Moon is Down presents far-reaching questions for Europe today. How much of victory and defeat is psychological? Should we make room for the psychological in our theory of victory? If so, what are the limitations of this? Militaries know of cognitive warfare, but can populations be trained in this too? If so, how can that be done most effectively? What ethical issues must we work out?

In the past, victory and defeat were clear from body counts and material damage. However, those measures are outdated today. As Bohdan Krotevych, Ukrainian veteran officer and security/intel professional, argues, Russia can absorb high casualties and continue to fight. He suggests that the Western view that loss of manpower will stop Russia reflects a misunderstanding of its military strategy. “This is how wars are lost,” Krotevych concludes.

This strategic miscalculation means virtually no investment today in preparing populations for unarmed resistance—that is, learning how to act, together, not just about media literacy and how to get out of the way in the event of a crisis. Although the resistance in The Moon is Down received some outside help near the end, it was primarily self-reliant. Can unarmed resistance strengthen Europe’s security autonomy? Without a doubt, it can at least reduce costs, enhance sustainability in defense, take effect before 2030, and help mobilize populations in a highly inclusive fashion. What's more, although lacking, we still have far more educational resources on unarmed resistance at our disposal than people did 84 years ago.

Hard lessons for the defense establishment and pacifists alike

No two occupation styles are alike. Credit: NAKO.

Few today have heard of this book, yet its ideas shifted the course of history. Although it is a very different world today, asymmetrical conflict dynamics are overall constant, and the desire for freedom is both universal and timeless.

The history of Steinbeck's book and findings from my independent research in the past year point to many hard lessens for those in defense, civil society, and humanitarian work alike.

For the defense establishment, they are:

- In the words of General Jean-Pierre Meyer, stop preparing for yesterday’s war. Humans are born with more than one “fighting” capability. While unarmed resistance is not a panacea, it still does not hurt to further examine it.

- The term "civilian" means a lot of things. Involve also grassroots civilians, civil society, and other local actors in defense efforts, not just the private sector and elites.

- Revisit theory of victory to take into account the particularities of Russian-style warfare and occupation, instead of operating on outdated or Western ideas.

For civil society, civil resistance educators, and those driven by pacifism:

- Fighting for freedom is close to the heart. People resist as employees, mothers, neighbors, teachers... Contextual learning is necessary to inspire and instruct populations in the methods of unarmed resistance.

- Any education and training efforts of a population should strive to connect people to their country’s nonviolent histories. Familiarity and commonality, not generality, are key.

- Unarmed resistance education and training is an opportunity to connect Ukrainians and Europeans on a human level. Co-creation is key.

- Moralizing in times of crisis is a cop-out. The real work happens when you are working endlessly to be relevant and to defend a world that does exist, not a world that you think ought to exist. The true leaders of people are "upholders of common values", not ideologies.

For international actors (humanitarian, civil/military relations):

- We urgently need an international definition and international norms of unarmed resistance or civilian-based offense. Nevertheless, know that people will resist even without these, not in a bid for martyrdom but because they simply wish to be free. This makes recognizing and codifying the phenomenon all the more urgent.

Hindsight, foresight

Unarmed resistance is “a narrow, dangerous, uncertain but very real path towards a better world”, in the words of French graphic novelist Xavier Dorison in Le Château des animaux. What Steinbeck describes in his book is not as a panacea. It was, in fact, Ukraine’s only course of action in the first days of the full-scale invasion.

Despite the imperfections of unarmed resistance, I believe humanity has still not discovered a better alternative.

Despite the crushing obstacles to calling attention to this topic, I still believe it is possible to discover your collective power before an aggressor has reached your doorstep.

Despite the darkness of the hour in Ukraine and across Europe today, freedom and decency will return. Our memory of our ancient liberty will not let us rest.

Amber French-Griette

As a nonprofit leader and subject matter expert on wartime civic resistance, Amber French-Griette is leading work to fix a blind spot: unarmed civilian-based defense readiness to enhance autonomy and sustainability in European defense. Her work more broadly promotes a better understanding of strategic nonviolent conflict, an Anglo-saxon interdisciplinary field of study dating back to the 1960s. In 2025, she co-founded the Organization for Nonviolent Movements (ONM), a French think tank, and serves as ONM President.

Read More