Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Sara Vazquez MelendezJune 14, 2021

Abandoned billboard signs overlooking the Caribbean Ocean are spray-painted with #yankeegohome as you drive west on Highway 2 in Puerto Rico. The stories of displacement have become increasingly common since 2019. Entire communities, including elders, must find new homes as millionaires from Silicon Valley, the rest of the United States, and Europe buy up property.

These super-rich individuals are taking advantage of a bill that was passed by the right-wing conservative party and signed into law by former Governor Ricky Rossello as Act 60, before he was ousted from office in the summer of 2019 by the most widespread protests in the history of Puerto Rico. The law exempts foreign businesses and individuals from paying federal income taxes on capital gains, including U.S. source capital gains, on condition that they have a bona fide residence in Puerto Rico.

Passing laws to disenfranchise and dispossess indigenous people of their land is not new. The Spanish empire and other Europeans engaged in this nefarious practice in the late 1800s in Puerto Rico. They emulated the U.S. Homestead Act of 1862, which enabled the U.S. government to dispossess Native Americans of their land. The current period in Puerto Rican history is no different.

In response to this new wave of settler colonialism, grassroots groups are waging nonviolent occupation campaigns to reclaim buildings and land, engaging in grassroots fundraising to empower peasants, utilizing social media platforms, and coordinating with the Puerto Rican diaspora to popularize their struggle. And the stakes are much higher than at first glance: less indigenous-owned agricultural land would mean more food dependency and environmentally unsustainable practices—with potentially major long-term consequences for Puerto Ricans.

From #AbolishAct60 to parallel institution-building—and beyond

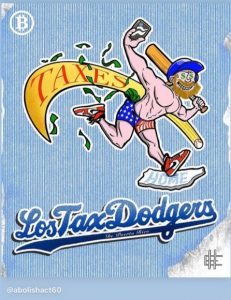

Source: Twitter user @abolishact60.

A grassroots group called #AbolishAct60 has been using social media platforms to educate the public about the act and its repercussions for Puerto Ricans. This has included networking with Puerto Ricans from the diaspora in the United States to call their senators and congresspeople, as well as using internet memes to amplify the injustices that Act 60 brings to the island. But the organizing goes well beyond raising awareness.

Grassroots organizers are nonviolently occupying buildings in urban areas, such as Caguas and Rio Piedras, to prevent these areas from being gentrified. The occupied spaces are being used for apoyo mutuo (mutual aid)—as epicenters for parallel institution-building, even—in the face of government negligence since Hurricane Maria in 2017. Some of the spaces initially served as shelters and community redistribution points for food and supplies sent from the diaspora. Mostly run by women, many of the spaces are also now used to run after-school programs for children, in the wake of a massive school closure campaign. (Former secretary of education Julia Keleher, who initiated the campaign, ended up facing federal charges in part for having granted school property to a developer for $1 in exchange for a luxury apartment).

Grassroots organizations are also raising funds for landless peasants to buy and own land. For example, the Fideicomiso de Tierras Comunitarias para la Agricultura Sostenible (Land and Community Trust for Sustainable Agriculture) has been raising money to buy agricultural land for farmers who are committed to using sustainable practices. I myself am part of a group that will soon launch another such fundraising campaign. Puerto Rico imports 85% of its food, making food sovereignty and sustainable agricultural practices dire needs. During the past decade there has been a resurgence of young farmers engaging in sustainable practices and building a movement towards food sovereignty.

Another form of resistance has included land seizure, where people nonviolently occupy farming property that has not been used for over 50 years, in hopes that it will be recognized by community members and produce a change in ownership—from private to collective ownership. This form of occupation is known as ocupación con conciencia, or conscientious occupying. Nonviolent occupiers meet with community members to share their vision for using the space and thus directly engage the community in their efforts. Their strategy is one of transparency, of creating sustainable communities through mutual support and community collaboration.

The future of Puerto Rico's decolonial struggle

In 2019, a chat was leaked in which Puerto Rican officials, including Rossello, stated that they were working toward a “Puerto Rico without Puerto Ricans.” In recent years, people have taken to the ballot box to push for change, but it hasn’t been enough.

Grassroots organizing and disruptive actions outside of the electoral process are helping to raise the heat on the current administration’s incompetence. Voiced grievances go beyond the housing and land crisis; they also include school damage from a 2020 earthquake, toll increases, privatization of the public energy company, disregard of environmental laws, ignoring femicide, and much more.

There is a common denominator between all of these demands, and that is transparency. This historical moment in Puerto Rico exemplifies the need to create a new path for the future we want. Decolonial struggles require collective rethinking, reimagining, and rewriting of narratives that our movement wants to see transcribed into the history books.

It is up to Puerto Ricans to build the future that we have been denied for so long: a just, sovereign, and sustainable Puerto Rico—and in particular, a future that allows us to preserve indigenous know-how to combat climate change. After more than 500 years of colonization, we have defended our land, our resources, our language, and our culture. Puerto Rico has a long history of civil resistance struggles that have been used to defend what we hold most dear to us: our connection to our land, our communities, and our ways of understanding and moving through this world.

We will continue to forge ahead with new and creative forms of resistance.

Sara Vazquez Melendez

Sara Vazquez Melendez is an anthropologist, farmer, activist and educator in Ponce, Puerto Rico. Through her school in civil resistance, and her agroecology farm, she provides a framework for decolonization, as well as methods for building an alternative future.

Read More