Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by James L. VanHiseAugust 03, 2021

In the spring of 2013, Turkish police made a public announcement at a metro station in Ankara warning passengers to “act in accordance with moral rules” after having spotted a couple engaging in a public display of affection. The admonishment backfired, and the next day, dozens of couples staged a “kissing protest” at the metro station. The incident went viral on social media, and a flood of photos and videos of couples kissing further flustered city police.

As eyewitnesses to the mass smootch-in, the police had to make a choice: do they risk looking silly by arresting the protesting couples, even though they weren't breaking the law? Or do they let the demonstration continue under their noses, which would raise the ire of the pious municipal authorities? The police faced a dilemma.

The book is part of the Brown Democracy Medal series. It is available via Cornell University Press and a free Kindle download is available via Amazon.

So goes the opening anecdote in Pranksters vs Autocrats: Why Dilemma Actions Advance Nonviolent Activism (Cornell University Press, 2020), by Serbian activist Srdja Popovic and Pennsylvania State University (USA) professor Sophia McClennen.

The kissing protest was spontaneous, but the authors contend that carefully planned “dilemma actions” can be extremely effective at getting media attention, attracting supporters, and fostering other important measures of tactical success in nonviolent campaigns. Such actions are intentionally designed to challenge an opponent in such a way as to leave them with no ideal response options.

“Dilemma actions are strategically framed to put your opponent between a rock and a hard place,” Popovic tells me in an interview. “No matter how your opponent responds, it comes with a price tag.”

Popovic was one of the leaders of Optor!, the Serbian youth movement instrumental in ousting dictator Slobodan Milosevic in 2000. He is now Executive Director of CANVAS, an organization that trains activists around the world in civil resistance strategies and tactics.

From his work with Optor! and CANVAS, Popovic knew that creative tactics like dilemma actions could have amplifying effects in the fight against authoritarian regimes or agitating for human rights. But to quantify the success rate of such actions, co-author McClennen suggested they do an evidence-based study.

As a social scientist, McClennen recognized the value of collecting hard data. “Srdja tells a ton of stories,” McClennen tells me on the phone in June, “but we should line them up with something else besides a lot of anecdotes. Let’s get some meat on the bones here.”

Although McClennen’s pilot study (the results of which were published in Pranksters vs. Autocrats) only looked at a small set of dilemma actions, the results were promising. For example, 98% of the cases drew media attention, 80% reduced fear and apathy among activists, and 81% attracted more supporters. When the actions incorporated a humorous twist—what the authors call "laughtivism"—the study shows they were even more effective at achieving beneficial outcomes for civil resistance campaigns.

McClennen stresses the research is incomplete. Along with CANVAS, she is working on a more comprehensive study involving about 300 historical cases where activists have attempted to create dilemma situations for their opponents.

“I do think we will be able to show that a group can have an outsized impact, in terms of the numbers in the movement, if they use dilemma actions,” says McClennen. “We think this is what is happening, but we want to prove it.”

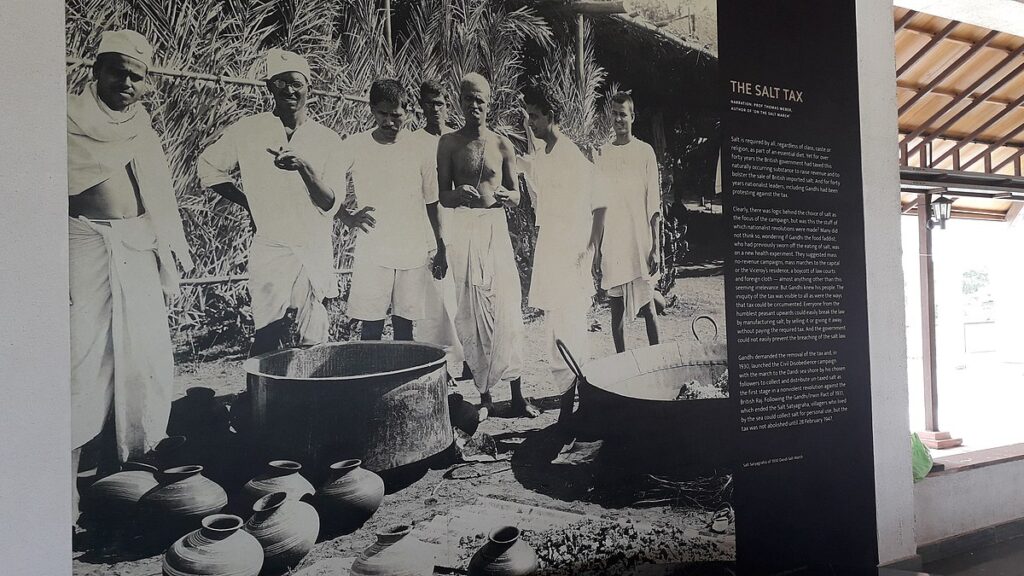

National Salt Satyagraha Memorial. Gandhi's salt march is a wel1l-known example of a successful dilemma action. Source: Sushant savla, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Lessons from Gandhi’s Salt March

The book refers to Gandhi’s 1930 salt march as an example of one of the earliest documented dilemma actions. Protesting the British tax and monopoly on salt production as part of his independence campaign, Gandhi organized a slow trek through India to the sea, where his announced intention was to gather salt as an act of civil disobedience.

This put the British viceroy in a quandary. Allowing the Indians to defy the Salt Act with impunity would not only show weakness on the part of the colonial government, it would also dramatize how ludicrous the law was. On the other hand, arresting Gandhi for defying the salt law would show that the mighty British empire is afraid of even a simple act such as the boiling of seawater, which could lead to more resistance among Indians. When Gandhi was eventually arrested, that’s exactly what happened.

The salt march illustrates a couple of key aspects to consider when planning a dilemma action. First, choosing issues that impact people’s personal lives will draw greater support from the public—and put more pressure on the opponent.

“When you are making a dilemma action, you actually don't start from the action,” says Popovic. “You start from widely-held beliefs.” That's what Gandhi did when he challenged the salt law, because the vast majority of Indians felt it was gravely unjust.

McClennen says dramatizing the issue in a way that gets the public on board is key: “You've got to frame the issue…in a way where an average person who is not part of your movement would say, 'yeah, this thing you're trying to do is totally fine.’”

The second lesson from Gandhi’s march is the importance of having a specific target and a concrete objective. If the goal is too broad or symbolic, it won’t create hard choices for your opponent. By challenging a particular law, Gandhi was creating a situation the viceroy could hardly ignore. In contrast, a protest against a broadly defined (or undefined) objective such as fighting climate change or patriarchy—while perhaps contributing to some long-term movement goal—doesn’t create a dilemma for an opponent.

Thinking about your adversary's default response is always a useful exercise when planning a nonviolent resistance campaign. You can take this one step further by designing the action to make that opponent’s preferred response less advantageous. This can limit their options and open up possibilities for creative responses on the activists’ side. Faced with an unfamiliar situation, an adversary may overreact and look foolish, or do nothing and look weak. Either option could result in a loss of face with the public and a net gain for the civil resistance campaign.

Preliminary data and anecdotal evidence suggest that creating a dilemma by limiting an opponent’s response choices can help get media coverage, recruit new members to a campaign, shift public perception, and ultimately change the narrative about a campaign issue.

With human rights and freedoms under attack globally from increasingly sophisticated autocrats, activists need to continually invent smarter resistance methods. Future research promises to provide further evidence that incorporating creative tactics like dilemma actions and laughtivism can increase a campaign's odds for success.

James L. VanHise

James L. VanHise is a writer who lives in Raleigh, North Carolina (USA). He has written about Gene Sharp and civil resistance in The Progressive, Peace Magazine, Waging Nonviolence and elsewhere. James blogs about nonviolent strategy and tactics at nonviolence3.com.

Read More