Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Markus Bayer, Felix S. Bethke and Matteo DresslerDecember 12, 2017

In July this year thousands of Polish citizens took to the streets to protest a judiciary reform they believed would threaten the democratic constitution of their country. During the protests, Solidarnosc leader and national hero Lech Walesa stated at a demonstration in Gdansk that it is now time to defend the democracy that they achieved through peaceful protests and civil disobedience in 1989. Consequently, President Duda felt compelled to use his veto and blocked the reform initiative put forward by the Polish conservative government: The Solidarnosc-Sheriff was back in town!

This picture shows a campaign poster by Tomasz Sarnecki to mobilize for the first free Polish elections in 1989 which brought to power Lech Walesa and the Solidarity movement. Source: Flickr user Lukas Plewnia (CC BY-SA 2.0, unedited).

Similarly, the people of Benin—who had initiated democratic change through civil resistance in 1990—acted as constitutional watchdogs in 2006 and 2016. Citizens rallied around the slogan of “don’t touch my constitution” when former presidents Kérékou and Boni tried to change the constitution to allow them to run for a third term in office.

In recent contributions to this blog, Maciej Bartkowski and Hardy Merriman discussed how nonviolent resistance (NVR) advances democratization and how it can assist to protect against democratic backsliding. This blog post, which offers a sneak preview of findings from a research project, focuses on if and how NVR campaigns can consolidate gains for civil society.

Civil Society Gains After Democratization

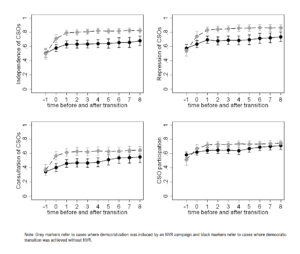

Our analysis, stemming from a research project on Nonviolent Resistance and Democratic Consolidation, is based on 101 democratic transitions that occurred within the time period of 1945 to 2006. Using data from the Varieties of Democracy Database we analyze improvements for civil society organizations (CSOs, i.e. interest groups, labor unions, religious organizations, social movements, and classic NGOs) after democratic transitions. We compare cases where democratization was induced by an NVR campaign (like Poland and Benin) with transition cases that did not feature an NVR campaign (i.e. violent or elite-led transitions). The four aspects of CSOs that we evaluate include: (1) independence from government, (2) freedom from repression, (3) consultation of CSOs for policymaking, and (4) participation in CSOs.

Click to enlarge. Figure 1: Four dimensions of prospects for civil society after democratic transitions.

Figure 1 describes the results. The graphs show average scores for the different indicators across the two groups of cases (i.e. with NVR-induced transition and without) from one year before the democratic transition occurred until eight years after the transition. The indicators were standardized so that higher values indicate better prospects for CSOs.

As shown in figure 1, NVR-induced democratic transitions clearly help to advance CSOs’ independence from governments and limit considerably the amount of repression that CSOs are confronted with. In cases of democratization without NVR, CSOs operate less independently and must deal with higher amounts of legal harassment and restrictions than in the situations when society was nonviolently mobilized.

Click on thumbnail for more information on the Nonviolent Resistance and Democratic Consolidation research project.

NVR also seems to improve aspects of CSO consultation, i.e. their degree of involvement in policymaking. However, only during the first four years after transition is there a substantial difference between NVR-induced democracies and those where democracy came about by other means. Afterwards, the gap between the two groups diminishes. Finally, the results reveal that regarding participation in CSOs, there appears to be no substantial difference between NVR-induced democracies and societies that achieved democracy without NVR.

These preliminary results indicate that NVR creates long-term gains for civil society, by institutionalizing rights for CSOs, which grant them independence and limit governments in their ability to repress CSOs. Three mechanisms may explain these results.

Nonviolent campaigns in defense of the constitution also took place in other West African countries, during the same period, including in Mali (pictured above). Source: Kassim Traoré/Wikipedia (public domain).

First, democracies with transitions driven by civic forces usually strongly value an active and engaged civil society. Second, as the examples of Poland and Benin in the introduction show, a public narrative reminiscing about past struggles for democracy can be a powerful symbol for people’s agency and a source to remobilize them in critical situations. Third, in cases of NVR-induced democratization, civic forces are powerful and well-organized and thus have the capacity to influence institutional reform, e.g. involvement in drafting a new constitution. At the same time, it is difficult for governments to exclude civic forces from transitional reforms, since they often rely on this constituency in upcoming elections.

One example illustrating these mechanisms is yet again Benin. Because of a mobilized society that pushed for a democratic opening, political elites opted for a démocratie intégrale—an integrative democracy that was reflected, among others, in active CSO participation in the drafting process of a new constitution. As a result, the constitution highly values personal freedoms and encompasses the right to resist any unconstitutional behavior—a right the people assertively exercised in 2006 and 2016. At the same time, many armed liberation movements, such as the Namibian South-West Africa People’s Organisation, forced independent CSOs and labor unions to join their ranks and subdue their goals under the higher goal of independence and liberation. This tight control is typically upheld after the transition to prevent the emergence of an organized opposition.

Takeaways for Activists and Policymakers

Our findings show that when democratic transition was achieved by NVR, civil society is usually well-equipped to institutionalize enduring rights for CSOs that help to defend democracy against future threats. But this also highlights that deposing a dictator is only a first step towards a better future — or in the words of Amilcar Cabral, one of Africa’s foremost anti-colonial leaders, we should not claim easy victories! If movements dissolve and their members return to their everyday lives after achieving democratization, this often has two consequences:

First, lacking a constructive program to transform the society, these movements tend to achieve short-term successes but leave structural problems untouched. To address this challenge, movements should develop long-term goals which, according to Bartkowski, must integrate a long-term strategy of constructive resistance.

Second, since these movements mostly establish liberal representative forms of democracy but seldom transform into political parties, they often leave a vacuum, which is frequently filled by former corrupt political or economic elites. Possible ways to address this problem include:

- Training activists to become effective policy makers in the transition process;

- Advising movements on how to become winning political parties;

- Encouraging and pressuring transitional governments to allow for more deliberative forms of governance (e.g. participatory budgeting, ombudsman institutions, referenda for constitutional changes, etc.).

We suggest that by using these tactics, civil society and nonviolent movements can serve as important watchdogs or ‘sheriffs’ for alerting the rest of society when democracy is in danger. Further, as a recent ICNC monograph suggests, these actors serve still greater purposes in the short- and long-term democracy project: They embody the democratic values they wish will reign in their country during the next chapter of history and beyond.

Markus Bayer

Markus Bayer is a Political Scientist and Ph.D. student at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany. His writings have been published in Peacebuilding and the Journal of Peace Research.

Read More

Felix S. Bethke

Felix S. Bethke is a researcher at the Cologne Centre for Comparative Politics and an Associate Fellow at the Institute for Development and Peace. His current research focuses on how civil resistance influences political developments.

Read More

Matteo Dressler

Matteo Dressler is a Programme Officer and researcher for the Conflict Transformation Research programme of the Berghof Foundation. His current research focuses include nonviolent resistance, inclusivity in peace processes and post-conflict armed social violence.

Read More