Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Julius OkothAugust 02, 2022

Nonviolent actions like naming and shaming corrupt politicians can be just as effective as advocacy campaigns at placing integrity and accountability at the center of election debate. And while organizations can help uproot corruption, what it really comes down to is forging a united front against corruption across the ordinary people that form the voter base itself.

High-octane politics have emerged in the lead-up to the August 9 general election in Kenya. Emotions run high around such events, and voters usually support candidates based not on their merit but their ethnic affiliation. Politics reverts to its factory settings—tribalism; a battle of ideas between reformists and the status quo; new hustlers versus old dynasties; integrity versus impunity; battles of gender; and debates on which economic model is revolutionary (bottom-up, trickle-down, or otherwise). Political parties are regrouping into tribal alliances, readily opting for betrayal, back-stabbing, plotting and political corruption in order to find their way into Parliament and Country Assemblies.

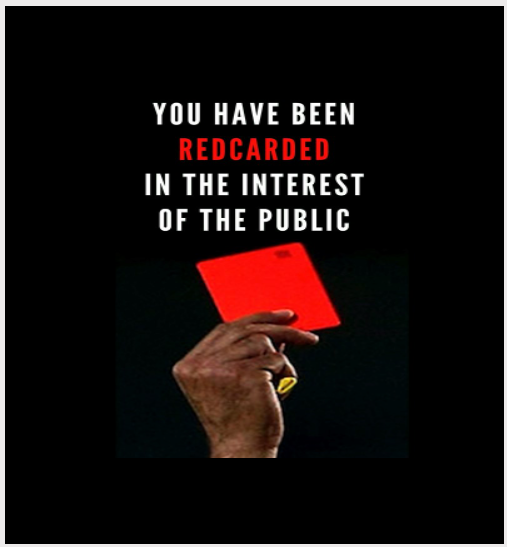

To combat such deeply rooted political problems—in particular, corruption—nonviolent movements, faith-based groups, and other community actors have emerged as a last line of defense, with noticeable participation of media actors, to boot. Primarily through naming and shaming, petitions, and “scrutiny debates”, Kenyans’ anti-corruption campaigns have aimed to promote ethical leadership anchored in integrity, whether locally or nationally. Below, I provide an overview of one such campaign, the Red Card Campaign, with the goal of highlighting effective anti-corruption organizing during an election season.

The National Integrity Alliance's #RedCardCampaign2022.

The Red Card Campaign

Click to enlarge. Communiqué of a red-carded candidate. Credit: Red Card Campaign Kenya Twitter account.

Using the popular concept of a football (soccer) penalty, the red card, the umbrella coalition National Integrity Alliance last May launched the 70-day-long #RedCardCampaign2022 as a public integrity drive to stop candidates who have been impeached or indicted from vying for various positions in the upcoming election (a similar campaign was also used in South Korea in 2000). Red Card Campaigners typically post revealing information about a candidate’s past actions on social media, or literally flashing a red card to disrupt candidates’ rallies to identify them as having a track record of crime or corruption. The National Integrity Alliance comprises a number of anti-corruption organizations such as Transparency International Kenya and the Kenya Human Rights Commission. It also encompasses grassroots movements, including Ni Sisi!, which organizes across faith traditions in Kenya for social justice and to combat corruption.

One Red Card Campaign action took place during a May 23 meeting between Kenya’s Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) and a number of presidential contenders. An activist shouted and held up a placard in protest of present candidates’ poor integrity until he was arrested. As part of the Red Card Campaign, the National Integrity Alliance also announced in a press release in May a list of 25 red-flagged contenders for political office… sadly, enough names to have to alphabetize them.

Impacts of anti-corruption organizing

Sheila Masinde, director of Transparency International Kenya, delivering a communiqué about the importance of vetting candidates for corruption in Kenya. Credit: Transparency International Kenya Twitter account.

Has the Red Card Campaign had any real influence on Kenyan politics this election season? For one, it has led the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) to submit to the IEBC a list of 241 aspirants with unresolved integrity questions. In addition, it has compelled the IEBC to bar former Nairobi Governor Mike Sonko, who was seeking the same seat in Mombasa County, and set in motion petitions for barring red-carded candidates from running in the election (one example here).

Perhaps most important, the Red Card Campaign has inspired citizens to start talking about ethical leadership in public fora. Kenyans have seen the importance of voting for competent, ethical and incorruptible leaders capable of championing good governance. The people of Kenya see themselves as holders of sovereign power to elect honest leaders, taking into account that it’s the people themselves who ultimately bear the consequences of poor governance.

How do I know this?

I have come to these conclusions not only from discussing politics with people around me, but also from attending or watching debates in the lead-up to the election. Debate moderators openly scrutinize moral and ethical integrity of candidates; they sometimes even make a mockery of sub-par candidates’ résumés, unethical actions they committed, or immoral comments they made on social media. These “scrutiny debates” are being organized both national and locally, usually by community-based organizations and grassroots movements. “Integrity” and “corruption” have found their way into these public discussions about politics, indicating broader awakening of the Kenyan conscience.

Indeed, in a political system intended to reflect the will of the people, consciousness—identifying corruption as a cross-cutting issue affecting people regardless of political affiliation—is the first step toward real change.

Takeaways for election day and beyond

Election observer badges for Kenya 2022 presidential election. Credit: County Governance Watch Kenya Twitter account.

Based on the experience of previous elections, it is rare to witness violence on election day in Kenya. Still, heightened tension will surely come to the fore as results begin to stream in on August 9. Civil society and faith-based organizations who engage in peacebuilding and violence prevention are organizing to observe at the polls and diffuse any threat of violence or voter intimidation. Should any protests break out on election day, it is incumbent upon pro-democracy activists in Kenya to maintain nonviolent discipline and encourage those around them to do so as well. This is one thing we have learned from fellow pro-democracy activists worldwide who hit the streets on election day.

On the same note, perhaps activists in other parts of the world might appreciate a few takeaways from the Kenyan context. First, building resilience to corruption is key. This means keeping the spirit of active citizenship alive across all levels of society—not just through advocacy campaigns, but also direct actions targeting corrupt politicians. Activists can establish community-led vetting committees and even implement their own Red Card Campaign. Direct actions like this can be just as powerful as pure advocacy campaigns at placing integrity and accountability at the center of political debate.

On an individual level, people who want to get involved in combating political corruption can volunteer for anti-corruption organizations, especially local grassroots groups that work across faith and religious divides. Because above all, while many institutions do help uproot corruption, what it really comes down to is forging a united front across the ordinary people that form the voter base itself.

Julius Okoth

Julius Okoth is a social justice crusader based in Nairobi, Kenya, and currently serves as coordinator of the Kenyans for Tax Justice movement. Julius is an alum of ICNC’s Learning Initiatives Network Fellowship (2016).

Read More