Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Laurence CoxApril 11, 2022

If activists are resisting an incinerator in one town and the neighboring town is resisting a megadump, how can they get beyond just fighting their own battles in isolation? How can they link up those different struggles and push for environmental justice? And how can they work together with other groups to challenge the underlying economics and incentives that produce waste in the first place?

When activists talk about issues like climate collapse or the rise of the far right, global inequalities or femicide, they don’t expect the issues to solve themselves. But the kind of agency that activists need to tackle these kinds of problems is far bigger than any individual organization or campaign.

If we share each other’s outrage or critiques of the status quo, we might feel like part of a movement, but without shared action and strategy towards systemic change, there isn’t a movement. Learning to work together across difference is a major milestone. The skills to make this happen are part of what I call the “ABC of activism” in my book Why Social Movements Matter (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018).

The ABC includes connecting up campaigns in different places and countries. It embraces intersectional work tackling inequalities of class, gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, ability/disability, etc. within our organizations. It also comprises forging both immediate coalitions and strategic alliances between movements around different issues and between different communities in struggle. This means thinking more deeply, about the structural and systemic problems we are facing, and more strategically, about how to build the power we need for the change we want.

Beyond organizational patriotism

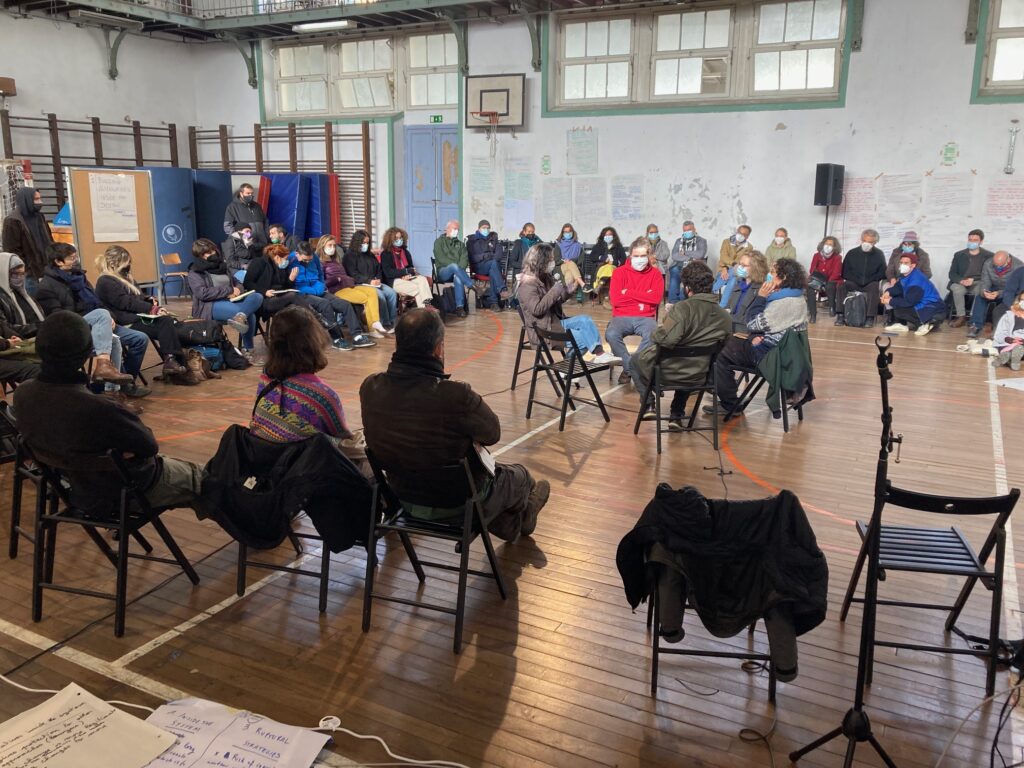

Ecosocialist Encounter, Ecology of Social Movements session (Ulex), Lisbon, 2022. Credit: Erasmus+ Programme partners.

In order to go from an organization to a movement, activists have to overcome what German speakers call “organizational patriotism” (Organisationspatriotismus, a generic term that has been applied to everything from strategic planning to business theory). Organizational patriotism includes narrowly prioritizing your own organization’s interests over all others. It means siloed social media work (not signal-boosting related organizations) and training programs that fail to mention other organizations working on the same issues. Organizational patriotism happens when organizations neglect networking and alliance-building. There are many other organizational forms and practices that keep us acting and thinking in separate boxes—as if our organization alone could do it all.

If we are serious about overcoming the problems we face, what we ultimately need—as frameworks running from intersectionality to climate justice acknowledge—is very broad alliances of movements, or far larger, more diverse and internally complex movements. Becoming able to act as “the peace movement”, “the Black community”, “the climate movement”, “labor” and so on is a huge achievement, but not a resting point.

What can we do?

Regenerative Activism Conference, Ulex Project, London, 2019. Credit: Erasmus+ Programme partners.

Some movements have long-standing cultures of alliance-building and networking across organizations, social groups and countries. Organizations may start with experienced activists with good connections to other movements, communities and civil society actors, or stand in a tradition that values making connections. Yet many organizations don’t start from such an ideal place, and the forces of entropy and fragmentation are very powerful.

It is easy enough today to learn the technical skills of mobilizing for a campaign, building an organization, carrying out nonviolent direct action or using social media effectively. But there are fewer spaces to address the problems of organizational patriotism. And of course, organizations that aren’t having conversations about this problem are less likely to see the need to address it. So what can we do?

In earlier research about movement development, my colleagues and I asked activists how movements can build the strategic capacity to think about large-scale change over time. Two strategies that came up were:

- Building alliances across organizations, communities and movements;

- Creating the spaces and skills for movements to become learning agents.

A manageable way to start alliance-building is simply to hold a 90-minute meeting with a small group of people involved in your organization, your movement or your community. Name other communities, movements or organizations that are near enough—geographically, in terms of issues—that you could easily reach out to them; identify the benefits and challenges of doing so; and think about the wider basis for an alliance (geographical, thematic, in terms of which social groups are involved, etc.) And then set a realistic goal—concrete and doable—that could mark a first step towards a more strategic alliance.

Learning from and for movements

How do movements become learning agents? Three activist training networks already run pan-European projects geared to supporting activists learning to grow the movements we need for a better world. The Ulex Project’s Ecology of Social Movements course; the European Community Organizing Network’s Citizen Participation University and European Alternatives’ School of Transnational Activism already tackle this fragmentation in different ways.

Together with two researchers who helped run the National University of Ireland Maynooth’s masters in activism course (2009-2015) we are working on a year-long training program for activists and adult educators across the continent. The program includes two-week residentials framing an online course and local support networks. It is geared to supporting “transnational and transversal (across social groups and movement issues) active citizenship” and highlighting the skills and knowledge needed for this.

Like the various trainings mentioned above, the idea is to make this financially accessible on a solidarity economy basis and to ensure the workload is manageable. At the same time we expect that participants will welcome the opportunity to create some space in their work to go beyond “fire-fighting” and reflect on questions of strategic effectiveness. There is a time cost for doing this—but it is nothing compared to the costs of being permanently trapped in the endless cycle of simply reacting to crises.

Editor’s note: In addition to the above, organizations like Rhize and ICNC offer activist learning and leadership development opportunities throughout the year.

![]()

Laurence Cox

Laurence Cox is co-author of The Irish Buddhist: the Forgotten Monk who Faced Down the British Empire (Oxford University Press, 2020) and co-editor of the activist/academic journal Interface. He is Associate Professor of Sociology at the National University of Ireland Maynooth and has been involved in many different movements since the 1980s.

Read More