Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Hardy MerrimanMarch 25, 2021

This is the second blog post in a two-part series.

The first blog post is here.

For over a century, movement organizers have recognized the importance of developing knowledge and skills in civil resistance. Scholarship increasingly validates this view by showing the importance of training and strategy in movement success.

Reflecting this convergence of research and practice, activist training is now widely considered a foundational movement activity. But how do you implement this insight? If you don’t yet have a movement, or your movement lacks the capacity to hold workshops, where and how do you start?

My previous blog post offered a "knowledge management" framework to help activists think through information sharing and skill development activities among different supporters. The framework starts by guiding people to identify what groups they feel are needed for their movement to win, and then ensuring that each of those groups has adequate training, information, and educational resources. The needs of each group will vary significantly depending on the role that they will play in the movement.

Using this knowledge management framework can lead to additional questions, and I address four common ones below:

ICNC workshop on strategic planning in civil resistance. Credit: Mariam Azeem.

1. We don’t have any funding, so how can we organize trainings and other knowledge management activities?

If you have little or no funding available to support your efforts, a common impulse is to appeal to a well-resourced individual or organization (which may be outside your community) to provide a significant amount of funds. Such an approach may (or may not) be what’s needed, but it’s important to recognize that this seemingly “simple” solution entails some risk. For example, appealing to wealthy donors can divert your energies, skew your activities, create dependency, and foster divisions as allies disagree about how funding should be managed, or who should benefit from it. These dynamics are complicated—much depends on how funding is secured, from where funding originates, the terms under which it’s provided, who ultimately receives it, and how it is managed. Because of these potential downsides, it can be helpful to do an internal evaluation and consider your other options first, before you decide whether or not to seek assistance from relatively wealthy funders.

A first step in internal evaluation is taking stock of all the resources that you currently do have. What are your and your community’s assets and strengths? You may want to brainstorm this with your friends. As a general rule, the most valuable aspects of a movement, and key factors in its success, are its people, skills, knowledge, relationships, strategy, and creativity. You may not have the capacity to organize a multi-day training (yet), but if you have time and ability to read, write, speak, or otherwise communicate and receive information, you already have the fundamentals to start advancing a knowledge management strategy. If you know sympathetic people as well or have networks you can tap into, that’s even better.

Second, it can be important to broaden the question from seeking “funding” to seeking “material resources.” The term “material resources” includes funding, but also includes “in-kind” contributions of meeting space, food, services, technology, and other resources that a movement may need. Consider that sometimes in-kind contributions can be more valuable to a movement than direct funding (which can be difficult for a movement to manage). In-kind contributions also may be more likely to come directly from grassroots supporters than direct funding, and likely with fewer conditions.

Third, consider the advantages to your movement of relying on your community’s existing material resources to advance your strategy. For starters, this approach will foster self-reliance, and prevent your agenda and activities from being influenced by external interests (although there may be strong interests within your community that you want to steer clear of as well). In addition, generating material resources from within your community involves organizing, which means the process itself can strengthen your movement. Lastly, as stated, identifying your own grassroots support base can help you avoid some pitfalls and misguided incentives of seeking external funds. As a specific example of this, organizers that seek external funds may find they need to visibly mobilize before they can gain attention and secure material support. Ironically, this drive to quickly mobilize and get noticed (including by funders) can siphon resources away from critical but lower-visibility knowledge management efforts for core organizers (as I mentioned in my previous blog post).

Don’t necessarily assume you’ll need a lot of material support in order to succeed. In fact, civil resistance often requires far fewer material resources than other forms of political struggle. If resources reach the right people, even relatively small amounts can have a significant impact. For example, modest, targeted material support to core organizers can be highly effective if it enables them to dedicate more of their time to the movement. Powerful campaigns have sometimes started with a single talented core organizer who could commit their time fully to their cause.

Orienting towards the assets of your people and community, thinking creatively about the amount and kind of resources that are needed, and considering the advantages of building a self-reliant material resource base can help you think through the question of funding. Appealing for external support may then become a last resort rather than a first option.

2. We want to train people or create an organizing manual. How do we know what content to include?

ICNC workshop in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire, December 2018. Credit: Amber French.

A first step in finding out how to help people is to ask them and listen. What are their aspirations and grievances? How do they see their problems being solved? What skills and capacities do they and their communities have? What lessons have they learned from their own past efforts? What kinds of skills, knowledge, and help do they feel they need? Raising these kinds of questions and carefully listening to responses will help you develop workshops and knowledge resources that resonate.

In addition, after listening and building rapport, you can share your ideas and see how people react. For example, people you talk to may mention nothing about civil resistance training on their own, but will respond enthusiastically if you raise it as a possibility (in fact, this reaction is not uncommon). Then you can consider how people’s concerns, words, and feelings fit with what you are trying to do.

Once you get to planning actual workshop content, you can also check out a number of resources (for example, here, here, here, and here) on workshop design and exercises that can help you.

3. We're not sure who to work with. We don’t know any movement organizers. How do we find them?

If you know you want to start a movement and are looking for fellow organizers, first, I’d like to congratulate you. It may feel lonely right now, but it sounds like you may be a core organizer that can play a key role in any movement you develop. Whatever brought you to this point, it’s important to feel the power of your own choice and to believe in yourself.

On the question of finding others who feel similarly to you, here’s a method. Try to create a series of short educational opportunities, such micro-trainings that last for an hour, or half-day trainings if you have the capacity to lead them. Then see who shows up and distinguishes themselves as being highly motivated (note: credit to the organization Rhize for developing an organizing model using this technique and documenting it in a great downloadable resource). If you hold three micro-trainings and 20 people come to each, you will reach 60 people in total. If 10-20% of those people show strong engagement, that’s success. Those people could be potential core or local organizers. They also have their own talents, networks, and experiences they can contribute. Call them to a follow up meeting.

As a group of core organizers emerges, it can be strategically smart (if you have the capacity) to create significant opportunity and support for them (here's an example of how ICNC did this). When people distinguish themselves based on their own interest and motivation, try to give them the resources they need in taking their next steps.

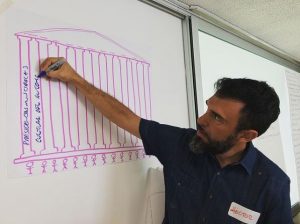

Understanding the pillars of support that uphold the status quo can be a critical tool in strategy development. Image source: RhizeUp Instagram account.

4. We don’t know any trainers, so who can lead our trainings?

This is a common question, which reflects a broader structural deficit. Demand for civil resistance trainers is high around the world. Unfortunately, there simply aren’t enough of them.

This scarcity is partly a result of a lack of educational infrastructure in the field—we don’t have enough institutions, resources, and learning opportunities available to develop a significant number of trainers. This state of affairs creates a self-reinforcing cycle, because without a significant number of trainers, it’s difficult to develop the infrastructure to produce more. By analogy, you need doctors to produce medical schools, and you need medical schools to produce doctors. It’s hard to build a medical system when you don’t have a lot of either.

Furthermore, the above circumstance is just one of several factors contributing to this deficit. Funding incentives, powerholder agendas, and misconceptions about civil resistance (i.e. thinking it’s just about protest, so how much is there to really know about it?) also contribute to this problem.

This lack of trainers is, in my opinion, one of the main challenges facing the field of civil resistance as a whole. However, solving this is a longer-term problem and in the meantime you have to start where you are. In fact, that’s exactly what many trainers chose to do at one point or another. Most did not rise from the comfort of a well-worn path of learning. Rather, they stepped out and started their own journey, often with little support, seeking out whatever resources and mentorship they could find in their available time. It’s not necessarily an easy path, but if this sounds like your kind of job description, then it’s there for the taking. Go for it! Believe in yourself. The rewards may well be worth it.

This means that if you’re looking for a trainer and not finding one, then maybe you’re the one you need. Recognize that you may also have strengths that an external trainer will not possess. Language skills, cultural competency, and local knowledge are all invaluable. If you have those, then the next challenge is acquiring relevant knowledge about civil resistance and movement organizing, and learning how to teach it. That is something you can do. ICNC’s Resource Library is a good place to start (and it has materials available in over 70 languages), and you can seek guidance and mentorship from others you know who have activism or training experience.

I hope the above short-form answers are helpful in spurring thoughts. Books and other resources elaborate on more nuances, complexities, and dimensions of these and other questions.

The instinct to organize trainings is a good one. It is based on a view that a movement’s skills and strategy matter. Seeing power and agency within ordinary people is a key factor in a movement’s success. Recognizing your own power to develop and carry out a knowledge management strategy can be a key factor as well.

Hardy Merriman

Hardy Merriman is President of the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict (ICNC), and led ICNC as President & CEO from 2015 until 2021. He has worked in the field of civil resistance for over 20 years, presenting at workshops for activists and organizers; speaking widely to scholars, journalists, and members of international organizations; and developing educational resources.

Read More