Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Kirsten HanJune 20, 2017

It took them decades to work up the confidence to publicly share their stories from that awful day, 30 years ago, when Singapore’s secret police showed up at their doors, rummaged through their homes, arrested them, deprived them of sleep and interrogated them in ice-cold rooms. Some took slaps across the face so hard that they saw stars. They were forced to say they were part of a conspiracy to overthrow the government and establish a Marxist state in Singapore. Their false “confessions” were televised and the media obediently published the government’s accusatory statements in full. But the charges were never proven, nor was there ever a single trial for the 22 volunteers and activists ensnared in government’s dragnet.

Even after all these years, “Operation Spectrum” has a chilling effect on civic life in Singapore. Citizens are still reluctant to challenge a government that can detain them, search their homes, seize their belongings, sue them, and charge them under broadly worded legislation. It seems much safer to operate according to the rules.

Meanwhile, those rules have become only more restrictive. For example, it is now an offense for anyone who isn’t a citizen or permanent resident of Singapore to gather in Hong Lim Park, the only space where people may gather for a cause without a permit. Under the guise of preventing “foreign interference,” the government has introduced yet another restriction to organizing and solidarity-building and a new worry for organizers, who now face the threat of prosecution if even a single foreigner is found at their event in the public park. Because of this new piece of draconian legislation, barricades and ID checks will be erected around Singapore’s annual gay pride rally for the first time in its nine-year history.

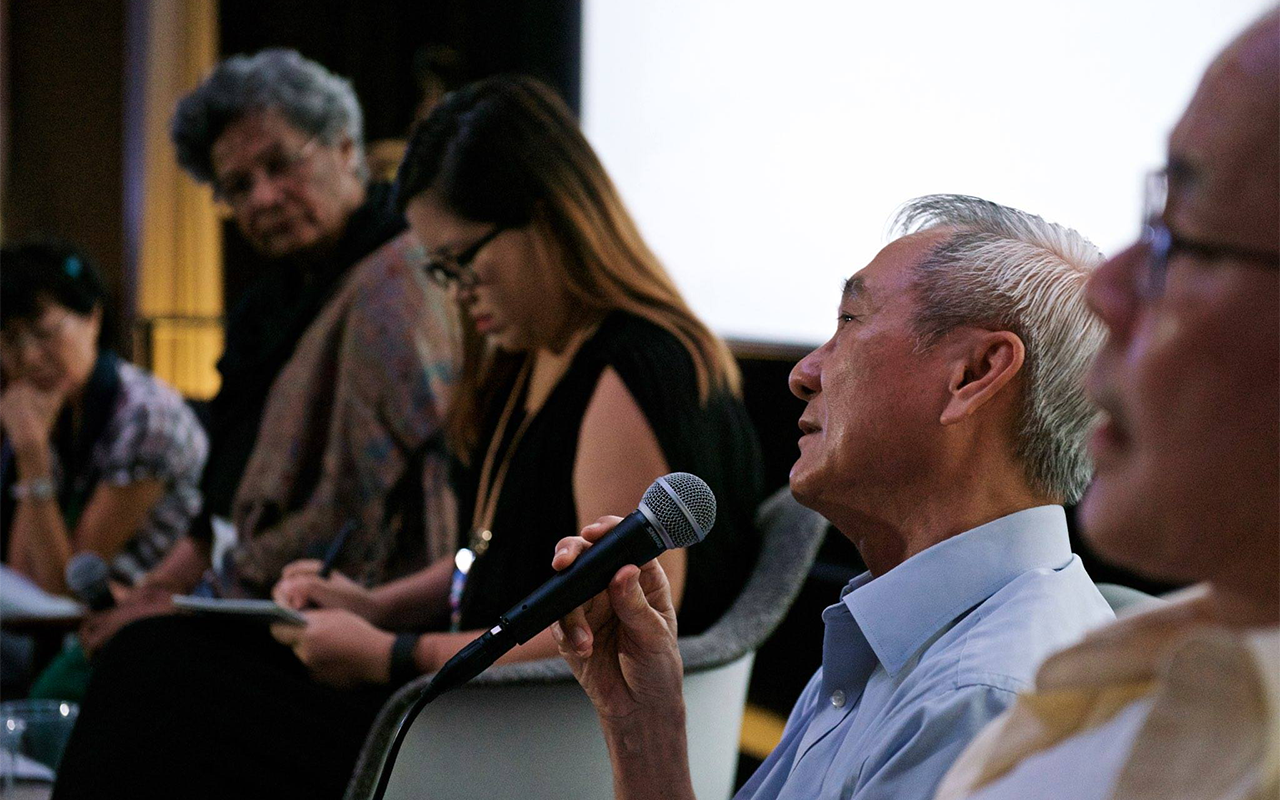

This is the story behind Singapore’s young, fumbling civil society today. We’re still grappling with the impact of that terrible time in 1987, whose trauma still lingers in ways large and small. Vincent Cheng, the alleged “ringleader” of the imaginary insurrection, shared at a commemorative event on May 21, 2017, that he despises a particular Chinese delicacy to this day because it was what his captors fed him after finally extracting his false confession.

Reclaiming Singapore’s History of Activism

Even before Operation Spectrum, organizing and advocacy work in Singapore had been fraught with apprehension and trepidation. According to activists from the period, the arrests set off a wave of paranoia and anxiety about being the Internal Security Department’s next target.

Constance Singam, who moderated a panel discussion among former detainees during the May 21 event, said the arrests were an attack on all of civil society and “made all of us cynical, fearful and suspicious of civil society activism and civil society activists.”

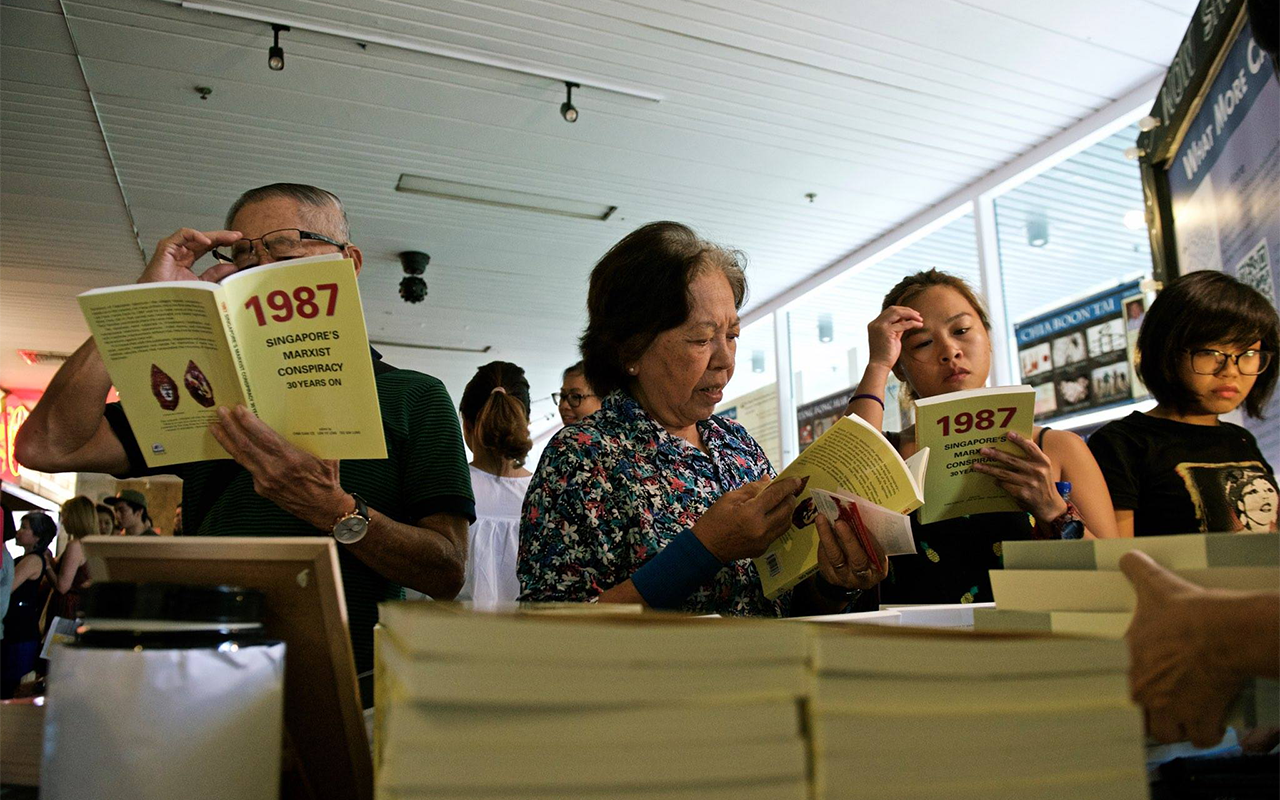

About two weeks after the May commemoration, eight activists staged a small protest in a public train, blindfolding themselves while holding up copies of the book 1987: Singapore’s Marxist Conspiracy 30 Years On. The police have since indicated that they are looking into the incident.

The long work of rebuilding and strengthening Singaporean civil society is underway. This year’s commemoration helped give oxygen to the search for answers, for truth and for the path forward. It was part of an ongoing effort to rebuild political consciousness in Singapore and reclaim its history of activism and organizing. Understanding our history is crucial to diagnosing the challenges we face and figuring out how to overcome them.

“The cost is that contemporary social movements in Singapore are amputated from their predecessors – their strategies, their truths, their pulse,” said young activist Kokila Annamalai. “How do we enliven political consciousness without excavating history? If there is no identity without memory, there can be no movement without legacy.”

Images in this article are attributed to Choon Hiong. See here for additional photos of the May commemorative event.

SaveSave

Kirsten Han

Kirsten Han is a Singaporean freelance journalist and activist, covering politics, human rights and social justice. She is the co-founder of We Believe in Second Chances, a campaign for the abolition of capital punishment in Singapore.

Read More