Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Janjira SombatpoonsiriJune 12, 2023

On May 14, 2023, Thai democracy made history.

Two opposition parties—Move Forward and Pheu Thai—gained the most and second-most votes in the national election (unofficially receiving 151 and 141 out of 500 parliamentary seats), defeating all pro-establishment parties, particularly the United Thai Nation Party led by former coup protagonist and Prime Minister, Prayut Chan-ocha.

This electoral blow has major implications on a possible pushback against growing autocratization in Thailand and other countries. It also showcases a pathway of collaboration between pro-democracy nonviolent movements and opposition parties.

Descending to the darkness of autocracy and repression

Since the 2014 military putsch, Thailand’s anti-democratic actors, especially within the army and the palace have tightened their grip by, among others:

- Drafting a constitution that creates an uneven electoral field;

- Politicizing military, judicial and bureaucratic powers; and

- Aligning elite interest with oligarchic networks.

Election day, May 14, 2023. Credit: Chainwit/Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0, unedited).

For many Thais, the past nine years have been a political nightmare as the Prayut-led government fails to tackle rampant abuse of power and corruption, human rights violations, widespread inequality, the COVID-19 crisis and economic recession. Because of these unsolved and accumulating crises, Thailand was referred to as the ‘Sick Man’ of Asia whose young people are increasingly disillusioned and thinking of migrating overseas. Against this pessimism and the trend of long-standing polarization, millions decided ‘enough is enough’, casting ballots for the opposition parties.

Most remarkably, this electoral win is despite—if not because of—sustained crackdowns on the opposition movements that primarily relied on nonviolent actions. My observation is that the establishment elites effectively crushed these movements on the streets. This is evident in the bloody military repression of the 2009-2010 ‘Red Shirts’ movement and the clampdown on the 2020-2021 youth-led movement, especially through digital technologies.

While this series of crackdowns undermined mobilizing capacities of the Red Shirts and later fragmented the youth movement, it has revealed the elite textbook for repression. This has in turn provided activists some insights on how to circumvent the repression. Most importantly, they have learned that extra-institutional actions like protests and boycotts alone are not enough to counteract autocratic encroachment. This formidable challenge requires institutional and policy overhauls, thus necessitating institutional allies and access to legislative power.

In this regard, I would like to draw at least three insights from the recent opposition victory about how interactions of various kinds between electoral politics and civil resistance can be productive in a broader societal pushback against autocratic creep.

Movement-party coalitions strengthen overall opposition resilience

Pita Limjaroenrat of the Move Forward party. Credit: Sirakorn Lamyai/Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0, unedited).

First, partnerships between civil society/movements and opposition parties can foster mutual resilience in the face of autocratic harassment. This characteristic coincides with the notion of a ‘movement-party’ (attributed to Herbert Kitschelt), tracing back to labor movements and parties in England in which the trade union movement morphed into the Labor Party in the late 19th century. In Thailand, elite attacks on opposition party Pheu Thai back in 2005 gave birth to the ‘Red Shirts’ movement that mobilized supporters against elite overreach. Brutally defeated on the streets in 2010, Red Shirt activists subsequently campaigned for this party, contributing to its 2011 landslide electoral win.

Similarly, Move Forward’s 2023 victory must be viewed broadly in light of the constitutional court’s dissolution of the party’s predecessor in early 2020. This prompted nationwide protests led by young activists who also made up the majority of party supporters. During the 2023 election, some of these activists launched the “Vote for Change” campaign in favor of pro-democracy parties. Conversely, after being banned as a consequence of the 2020 court ruling, former politicians of this party turned into activists and founded the Progressive Movement. This movement helps craft Move Forward’s policies and fosters collaboration across civil society organizations and like-minded parties.

Grassroots activist politicians help build public trust in opposition parties

Second, in the aftermath of activism failing to bear tangible outcomes, activists can still continue their advocacy by running as opposition party candidates. For instance, Rangsiman ‘Rome’, a former student activist leading anti-2014 coup campaigns was elected as a member of parliament in the 2019 election. Throughout his terms (2019-2023), he excelled as a whistle blower, exposing the establishment elites’ alleged involvement in corruption and abuse of power. His activism background and methods lent the pro-democracy movement a degree of grassroots authenticity.

Based on my interview with him in 2019, he shifted from activism to institutional politics because he wanted to “show the public that there are politicians who genuinely care and address public interests” to gain public trust in democracy. Similarly, a handful of former 2020-2021 activists ran as parliamentary candidates for the winning opposition parties. They tapped into advocacy skills during the campaign trail, while addressing public demand for political change and responsive governance.

Movement-party collaboration, at best, mobilizes against anti-democratic forces and, at worst, counters apathy

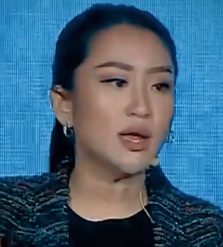

Paethongtarn Shinawatra of the Pheu Thai party. Credit: NewsClear/Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0, cropped).

Lastly, opposition parties with support of movements can effectively mobilize popular pressure to counter elites’ attempts at electoral manipulation. Due to low public trust in the junta-appointed Election Commission, before, during and after the 2023 election, civil society organizations and the opposition parties launched on- and offline initiatives to monitor possible electoral irregularities. When opposition candidates spotted suspicious behaviors that could tamper with the electoral integrity, they rallied their supporters to expose these and demanded transparency from local election commissioners. Media outlets collaboratively created online platforms for real-time vote counts that keeps the EC in check.

Weathering the political storm

As of this writing, the elites in Thailand still hold on to their power. With the tendency to disregard popular voices, elite gatekeepers—including the junta-handpicked senate and the Constitutional Court—could hinder the opposition parties from forming the government. In this light, pro-democracy activists and voters are understandably frustrated; they have staged nonviolent protests to pressure the senators to respect the electoral outcome. This kind of extra-institutional action may be crucial in the absence of institutional outlets to channel grievances.

At the same time, in the post-election setting, this may be counterproductive for the opposition. The general public may perceive them as over-relying on street politics despite having just won the election. What’s more, in the Thai context, mass mobilization in the street can set the stage for military intervention. If that were to happen, we would be back to square one.

Under these circumstances, movements may consider taking their campaigns off the streets and refraining from radical rhetoric that could further entrench elite gatekeepers. This does not imply that movements should sit on the fence. In contrast, movements can continue their campaigns by, for instance, rallying public support for the opposition parties and forging alliances with institutional actors who have the power to convince elite allies to change sides.

Janjira Sombatpoonsiri

Dr. Janjira Sombatpoonsiri is currently a research fellow at the Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University in Thailand, and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies. Her research focuses on civil resistance, civil society’s pushbacks against autocratization, and digital repression in Asia.

Read More