Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Sayed Yusuf AlmuhafdhaJune 05, 2024

اللغة العربية

Sign up for the series launch webinar on June 21, 2024

English translation by author, with minor adaptations from the original Arabic by Minds of the Movement staff.

“The journey of misery and struggle for survival began," said Hani Al-Rais the Bahraini human rights activist. In the first moments when I stepped onto this land seeking political asylum, this truly reflected that I was determined to turn this journey into a path of challenge and achievement. Despite the resentment and cruelty of exile, the academic and personal growth I have attained today, which I wouldn't have achieved in my own country even after spending years there, has eased this resentment.

One of the many peaceful protests I participated in before exile. Credit: Anonymous photographer.

Human rights work in the field

From 2006 until late 2013, I worked in my homeland of Bahrain in the monitoring and documentation department of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights. My work involved regular communication with victims and survivors to document the violations from which they suffered and referring them to international rights organizations. I dealt with UN mechanisms and attended most of the demonstrations calling for democracy, human rights protection, livelihood demands. At these demonstrations, I monitored how security forces handled the mostly peaceful protesters, capturing photos and videos.

The absence of independent and objective journalism in Bahrain compelled me to play the role of a citizen journalist to expose human rights violations through social media in both Arabic and English. My work drew significant attention from Arab and Western media outlets, especially during the Arab Spring revolutions in the MENA region.

I was arrested for his human rights work. I eventually went into exile in Germany in 2014. Credit: Anonymous photographer.

Once on the other side…

I ended up in exile after being imprisoned several times for my human rights activities. I was subjected to smear campaigns in the press and on official television, which prompted me to move abroad to continue my human rights work. Yet even after leaving Bahrain, I still suffered from repeated online harassment. Further, this transition meant losing the direct connection with fieldwork, with victims, and with my ability to document events first-hand.

The challenges as a migrant are numerous, countless even. For example, learning the German language and understanding Germany's political and legal system. My English fluency did not seem to assist me much in my early years of settling. Acquiring a job that aligns with my qualifications and experience was a significant challenge as well, since in practice there are specific jobs for immigrants who live in Germany and are learning German as a second language—regardless of whether the immigrant has German nationality.

Certification equivalency is another hurdle that migrants face, as the evaluation system only accepts qualifications from within Europe, making it difficult to have credentials from elsewhere recognized. Raising children in a German society is also a huge challenge as we strive to strike a balance between integration into the German community while preserving their Arab identity, values, culture, and language. Longing for their homeland and yearning for home and family pose the greatest challenge for every migrant, especially during religious, social, national, and family occasions. I long to share in the joys and sorrows with my family and can never shake the thought of losing my father while abroad and being unable to return and bid him a final farewell due to my human rights activism.

Nonetheless, once on the other side, I began exploring this rich experience that exile has to offer, with its various opportunities that weren’t available to me while still living in my homeland.

A refugee family relaxes outdoors in Germany. From exile, I am able to work freely and return home at night without fear. I was also able to join local efforts to support refugee and migrant integration. Credit: Self.

What every human rights defender dreams of

Despite all the difficulties mentioned, the experience of exile offers some advantages. It allows you to think outside the box; it grants you freedom, peace, and enough time to grasp the challenges in your country at their true scale, with all their complexities locally or regionally. These elements are unattainable when living in your homeland, especially in our societies where many public figures, whether politicians or human rights activists are either imprisoned, put on trial, or dismissed from their jobs. Some are busy just trying to make a living, while others are trying to avoid arrest as much as possible. They must be cautious about every word or action they take, fearing imprisonment or punishment—a price not every activist is willing to pay, which is legitimate and justified.

Since I’ve been in exile, I have had the chance to communicate directly with the international press and organize human rights events with international bodies more easily. I am now able to organize solidarity protests without having to run from the police or carry onions and handkerchiefs to ease tear gas effects. Communication with human rights organizations via mobile phone is now possible without surveillance. I can share all events on social media without being detained for allegedly spreading fake news or tarnishing Bahrain's reputation. I can travel to European countries with my ID card to participate in human rights events without facing interrogation, harassment at airports, or being prevented from entering certain countries. My human rights activities did not prevent me from finding employment at a German company, unlike in Bahrain, where I was blacklisted for political reasons after being fired from my job.

This ideal space that I have enjoyed since 2013 is something every human rights activist dreams of: to work freely and return home at night without fearing police raids, arrests, or house searches without a judicial warrant. This unique experience has not been limited to human rights work but has extended into engaging in German public affairs, becoming a member of local organizations and institutions, as well as volunteering in projects supporting refugees, migrant integration, and drafting public policies to address racism, discrimination, and right-wing extremism. This has helped expand my international network to include German speakers.

Residing abroad has allowed me to pursue an undergraduate degree in human rights and philosophy at an American university in Berlin. I was granted a scholarship to complete a Master's degree in human rights in Vienna, Austria. This enabled me to work as a trainee at the German Ministry of Justice in the Human Rights Department and represent Germany in an official delegation at the Human Rights Council session in Geneva, discussing Germany's part in the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

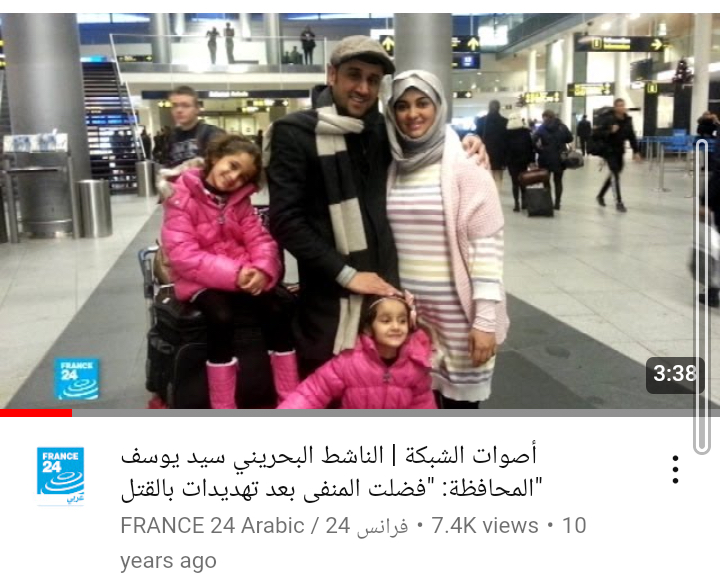

My family upon arrival in Germany.

This is a glimpse of a story of struggle blended with success and failure, filled with challenges, difficulties, and significant opportunities. I wanted to share these experiences with the esteemed readers of this blog to convey a message to all immigrants on how they can become great ambassadors for their countries, utilizing all spaces and opportunities to enhance themselves and advocate for human rights in their home AND destination countries.

Sayed Yusuf Almuhafdha

Sayed Yusuf Almuhafdha is a prominent human rights defender, researcher, trainer and expert with 15 years experience in human rights advocacy in Bahrain. In spring of 2014, Sayed went into exile in Germany, following continuous judicial harassment and threats to his life.

Read More