Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Chaminda HettiarachchiJuly 20, 2022

On July 9, members of Sri Lanka’s #GotaGoHome movement surrounded the presidential secretariat and the presidential palace in the capital of Colombo. They called it the “Final Push” of their nonviolent campaign to oust now ex-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Their list of grievances: mismanagement, corruption, nepotism, intimidation, alleged war crimes, alienation of minorities, and the role they felt Gotabaya and his government played in sinking their country into numerous crises.

Since that day, images of ecstatic protesters swimming in the president’s pool and jumping on a bed in Gotabaya’s home have been circulating worldwide. In an instant, these joyful images internationalized protesters’ mockery of Gotabaya’s luxurious lifestyle in contrast with their own misery.

After several unsuccessful attempts, the president secretly fled the country, finally reaching Singapore on July 14, where he is supposedly seeking asylum. From there, he officially resigned by ending his presidency prematurely (two years and eight months, instead of five years). Meanwhile in Colombo, the people celebrated the first main victory of their three-months long campaign.

Although these achievements are important, it is crucial to understand that this is only the beginning of the struggle. Parliament has just today elected a new president, Ranil Wickremesinghe, Gotabaya's loyal ally and now former Prime Minister. Wickramsinghe is an experienced politician seen by many activists as capable of using foul play to hold onto power. Thus, a long, hopefully nonviolent struggle for a more democratic Sri Lanka has only begun.

This post analyzes the context leading up to movement launch, the trigger event, and impacts of its first several months. My companion post here goes into further detail about prominent nonviolent tactics being used, as well as obstacles and next steps for the movement at this extremely crucial juncture.

A contested election, increasing entrenchment

Gotabaya Rajapaksa came to power in 2019 promising a “prosperous nation” for all Sri Lankans by following a one-country, one-law approach (Sri Lanka has a mixed-law system that functions on the basis of ethnicity). He won the 2019 election with 52 percent of votes vs. 42 percent of the runner-up, with an overall voter participation of 81.5%. After his win, Gotabaya secured a two-thirds majority of seats in parliament in August 2020 and tightened his grip on power by amending the constitution.

However, Gotabaya had a questionable track record even before his appointment. He was accused of corruption, intimidation, and war crimes. His eligibility to run for president as a dual citizenship holder of the United States was also challenged. However, he was able to win the election by dividing people along ethnic and religious lines and attracting the majority ethnic group’s votes in large numbers while minorities did not vote. Gotabaya himself declared that he was the president of the Sinhala people to satisfy his voters of the majority community. Meanwhile, he took actions to alienate minorities, further exacerbating the country’s polarized society.

On top of accusations of Covid crisis mismanagement, the Sri Lankan government under Gotabaya’s rule could not provide even basic needs of the people such as cooking oil, fuel, electricity and food. Kilometers-long queues to obtain such goods were not uncommon. At the same time, his regime appeared insensitive to people’s suffering and continued to lead luxurious lives at the expense of ordinary people’s livelihoods. Opposition political parties, unions, and civil society groups could not challenge Gotabaya’s regime, as they were divided themselves, and Gotabaya benefited from strong support from media, the business community, and the educated elite.

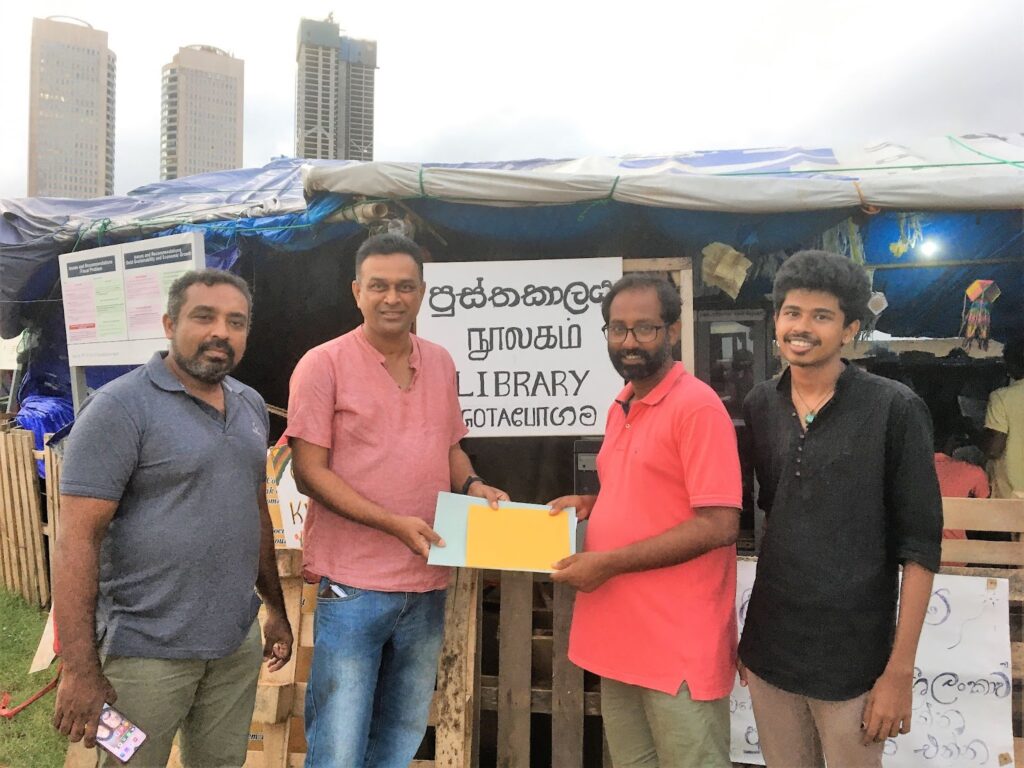

All photos are of GotaGoGama in Colombo, courtesy of author (article continues below).

Trigger event and the emergence of GotaGoGama sites

It was against this backdrop of multi-level national crisis that a group of young protesters started a social media campaign #GotaGoHome in January 2022. These youth were mainly apolitical, non-partisan working professionals. Fueled by ordinary Sri Lankans’ grievances, the movement had no trouble gaining momentum, as evidenced by what is described below.

The first action beyond social media took place when the group surrounded the president’s private residence in the outskirts of Colombo on March 31. It can be considered a trigger event. The police made several arrests and used tactics such as social media bans (which he canceled the next day due to mass protests), imposing curfew and emergency laws after the event. Despite the crackdown, the damage to the regime had already been done: the president whom the people of Sri Lanka believed to be all-powerful was in fact vulnerable.

On April 9, the protesters occupied Galle Face, a park in central Colombo. They blocked the entrance to the presidential secretariat. This move was very successful as people of various backgrounds from around the country joined the action. As a result, a permanent occupation site called “GotaGoGama” (GotaGoVillage) was built, modeling a typical village in rural Sri Lanka. GotaGoGama is a very interesting and attractive place where a university, school, library, hospital, IT Center, and many other community spaces have been built.

The occupation site has been attracting many visitors including celebrity artists, opposition politicians, sports competitors, professional groups, national celebrities, and media personalities. GotaGoGama received widespread, positive media coverage, and additional GotaGoGama sites emerged in other Sri Lankan cities as well as in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and many EU countries to support the movement. The original site in Colombo remains the epicenter of the #GotaGoHome movement.

Read my companion post here for an overview of nonviolent tactics being used, as well as analysis of obstacles and next steps for the movement in the coming months—which will no doubt prove crucial for the future of Sri Lanka.

Chaminda Hettiarachchi

Chaminda Hettiarachchi is a political analyst, academic, technology management specialist, and social entrepreneur based in Colombo, Sri Lanka. In 2016, Chaminda attended the 2016 ICNC Summer Institute held at the Fletcher School, Tufts University (Boston, USA). He has also completed an executive education program at Harvard Kennedy School and was a DAAD Scholar at Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany and University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany.

Read More