Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Phil WilmotFebruary 08, 2018

My entire worldview was turned upside down when I learned about nonviolent resistance. I remember the joy I felt, the hope. I slept that night with a flame in my heart that would never die. I believed to my core that every evil and ill in the world could be made right.

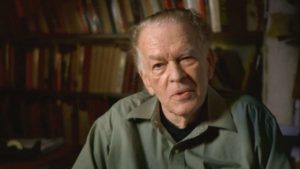

The scholar Gene Sharp (1928-2018). Source: PRIO.

“It works,” I thought to myself, “but how?” My university classes didn’t discuss the nitty gritty of people power. I had to know more.

That’s how I came across Gene Sharp. Like other old white male academics, he devoted much of his life to codifying a niche topic, in his case nonviolent resistance. As I read his works, I felt I was basking in the shadow of someone who had a secret about how to fix the world.

From Dictatorship to Democracy — now translated into about 40 languages and available in the public domain — was the most foundational and succinct of his texts. It discussed how ordinary people could harness collective power to oust the most militaristic and oppressive regimes.

I sought more depth and came across his trilogy discussing the dynamics, methods, and politics of nonviolent action. In The Methods of Nonviolent Action, Sharp chronicles 198 nonviolent tactics using historical examples. I read about each one slowly and deliberately in a remote village of Lango, northern Uganda, reflecting on how my neighbors could utilize some of these insights to nonviolently challenge the dictatorship of Yoweri Museveni, or at least force the state to provide the village with access to safe water and electricity.

Little did I know what was brewing six hours south within the bustling city of Kampala. Young activists had formed Activists for Change, an anti-Museveni pressure group, and they were studying Sharp’s writings as well.

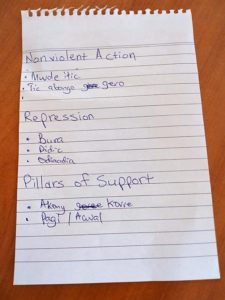

Activists of northern Uganda begin translating Sharp terminology to Lango. Source: Author.

When you read about the seemingly impossible, glorious things nonviolent resistance has achieved — like the termination of dictatorships, military occupations, and colonial powers — you can’t resist the temptation to put some of the theories of nonviolent resistance to the test. While central Uganda was boycotting regime-friendly companies, staging industrial strikes and marching in the streets, I was trying to figure out how to help my neighbors resist a massive land grab by foreign companies. Unaware of one another at the time, we were simultaneously applying different forms of nonviolent resistance Sharp had taught us.

Eventually our paths crossed, and we decided to form an institution that could disseminate Sharp’s teachings to people oppressed enough to see its merit. Since 2012, I’ve been sharing leadership roles in Solidarity Uganda, where I have the privilege of training and learning from activists and movements across the African Great Lakes region. I really don’t know where I’d be in the world today if it had not been for Sharp’s work.

Sharp’s work appealed to me because of its almost militaristic analysis of power. I had been socialized to associate peace with weakness, to understand it superficially as mere abstinence from violence, as something too idealistic to function effectively in political battle. Sharp’s understanding of nonviolent action dealt directly, and perhaps confrontationally, with matters of power. It was about compromising an opponent’s sources of support and resources. It was about presenting a nonviolent threat to those whose actions stood in the way of your interests and survival.

This was groundbreaking. It was a game-changer. And although examples of nonviolent resistance speckle thousands of years of human history, the past two centuries have witnessed an immense upsurge in its relentless application on a mass scale. All my cynicism about the future of our planet and species dissipates while reading Sharp and witnessing his theories being put to practice every time I watch the news.

Translating civil resistance terms into Lango, a language spoken in northern Uganda. Source: Author.

Sharp missed the mark on many things, as pioneers in any field unavoidably do. He was forthcoming about offering a mere starting point. His well-circulated 198 methods of nonviolent action are by his own admission incomprehensive.

A group of activists across the world called Beautiful Rising, including myself, decided Sharp’s work needed a next generation — one mindful of the new tricks and elevated wisdom of authoritarians, since the terrain of civil resistance is changing, and our opponents are getting smarter about how they administer repression. In 2015, we started codifying new principles, tactics, stories, and ideas pertaining to civil resistance with a particular emphasis on the global south.

The Beautiful Rising network involves workshops, writing, generating content for the website, offline toolkit, chat bots, video chat groups, publishing books, physical gatherings, and many other activities. It is a global network that has continued to grow since 2015. Our discussions also revolve around principles, or major considerations that guide how we organize: For example, “let victims lead,” “know when to lose a battle,” “practice intersectional organizing,” “don’t sacrifice self-care,” and so on.

But Beautiful Rising won’t be the network that gains the same level of notoriety as Sharp. That honor will go to those people of the next generation of activists who codify matters of community organizing and intersectionality with as much intensity as Sharp codified the mechanics — the tactics and strategies of people power. No critical mass is sitting around dormant, waiting to be activated, as Sharp’s writings inadvertently made me assume. Even those masses that have the potential to engage in civil resistance also struggle with their own internal power dynamics begotten of differences in gender, race, sexual orientation, age, class, language, and educational attainment, to name a few. Those who make as much sense of matters of community organizing and intersectionality as Sharp did of nonviolent resistance strategy will go down in history as notably as Sharp has.

I’m not yet ready to make sense of all the dynamics of something as complex as civil resistance. But I can start by helping to translate Sharp’s works. I believe Sharp would take satisfaction in knowing those who are oppressed have access to one additional tool at their disposal to change their situation. I’ll do my best to help create that tool.

I know I’m not alone. This determined man had a direct and indirect impact on countless revolutions. In each of those revolutions are Sharp junkies like me whose mundane life journeys have been totally disrupted by the realization that with the power of ordinary humans like us, everything is possible.

Phil Wilmot

Phil Wilmot is a former ICNC Learning Initiatives Network Fellow, co-founder of Solidarity Uganda, and a member of the Global Social Movement Centre and Beautiful Trouble. Phil writes extensively on resistance movements and resides in East Africa. Write to Phil at phil@beautifultrouble.org.

Read More