Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Phil WilmotNovember 26, 2019

Few would contest that—north, south, east, and west—authoritarianism is on the rise. But how many would hold an optimistic view that the masses are effectively combating this trend?

In April, researchers at the Harvard Kennedy School called our attention to the exceptional success of African nonviolent uprisings. Africa has produced more mass movements than any other continent in the past decade, despite a horde of repressive dictators ruling over most of its nations. The success rate of Africa’s uprisings since the 1970s remains higher than that of any other continent. Through consulting movements in Africa, I’ve had the privilege of witnessing their tremendous impact first-hand.

No doubt the legacy of colonialism, predatory economics, and racism contribute to the ongoing sidelining of Africa in virtually all subjects of study—civil resistance not excluded. Preliminary efforts to form a community of those harnessing lessons on nonviolent resistance in Africa have been made by the Center for Social Change in Johannesburg. Global activist network Beautiful Trouble recently added 21 learnings from African resistance to its toolkit.

Still, more must be done to glean what we can from African movements. The continent is home to more than 50 countries, each with a particular social and political context, yet there is a dearth of information about what African populaces are doing to transform their political situations.

This year, the global spotlight was briefly placed upon Sudan during its overthrow of Omar al-Bashir, and to a lesser extent, Algeria’s popular resistance to Abdelaziz Bouteflika whose 20-year rule has met its end.

Yet 2019 has yielded at least nine other African political uprisings from which we can learn.

Madagascar

A mass of Madagascans came out of the New Year gate swinging. The first days of January were marred with primarily nonviolent protests and accusations of vote-rigging. In this case, a culture of normalized electoral fraud did not aid an incumbent, but instead Andry Rajoelina, a longtime political rival of Marc Ravalomanana. Rajoelina, a former DJ, held out against Ravalomanana’s supporters and remains the new president. Rice farmers continue to resist Rajoelina’s aggressive development projects which threaten to destabilize their paddies.

Resistance by Madagascans in 2019 continues to teach us that movements cannot merely mobilize around personalities but must fight for the direct interests of marginalized groups.

Cameroon

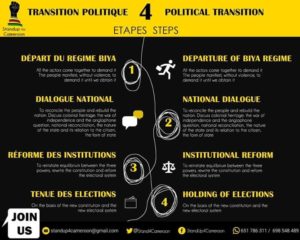

Click to enlarge. Steps for political transition in Cameroon (in French and English). Source: @Stand4Cameroon.

Cameroon is home to both Anglophone and Francophone regions, with the Anglophone regions (dubbed “Ambazonia” by some) the most marginalized and destabilized by Paul Biya’s longstanding regime. French-speaking Cameroonians aren’t too comfortable with his oppressive rule, either.

Mass lamentation protests by women have pressured armed groups—and political leaders—to take steps toward peace. These “wailing coalitions” are building a modern, women-led thrust toward political change.

Cameroon’s activists teach us the importance of organizing across borders, be they linguistic borders within a country, or continental borders, as in the instance of diaspora Cameroonians demonstrating against Biya in Geneva in June.

Mali

Power is not held solely by political leaders, but sometimes also by ethnic groups. In Mali, thousands rallied in the capital of Bamako in April, calling for an end to violent massacres. Campaigners also called for an end to President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita’s tenure, as well as a departure of United Nations (UN) peacekeepers from Mali. Even where violence and suppression of dissent carries serious risks, Malians are standing up in large numbers to call all who are sustaining violence to account.

Unlike many political movements that fight for national demands, they have called out opportunistic international actors such as the UN and demonstrated the importance of raising consciousness of the real interests of such institutions.

Moroccan activist Nasser Zefzafi. The dismissal of an appeal to release political prisoners prompted him to sew his mouth shut this year. Source: Wikipedia.

Malawi

Not typically known for protest culture, Malawians have built a protracted campaign against election fraud this year. Rather than solely targeting the incumbent, their dissent has focused on electoral commission chairwoman Jane Ansah, who has refused to resign.

The government has banned various protests, making it difficult for organizers to maintain momentum in recent months. Still, Malawian organizers reveal how waves of street actions focused on a specific political goal can ebb and flow over several months, raising the level of conflict along the way.

Chad

Chad’s dictator Idriss Deby has done a fair job of staying out of the international spotlight for three decades. In 2018, parliament proposed constitutional amendments that would enable Deby to retain power through 2033. Citizens rose up to challenge these reforms, and the government responded with a social media blackout that lasted 16 months.

Since then, numerous internet rights groups worldwide have offered VPN support to protesters, should Deby’s administration flip the switch again. Deby continues to deploy armed forces, claiming to fight militants, but in the process escalating insecurity. This atmosphere of instability, combined with a crippling economy, continues to ripen the fields for revolution in Chad.

If there’s anything Deby should learn from Bashir’s downfall, it’s that once people are queueing for hours to buy bread that is no longer subsidized, a dictator can start counting his last days.

Morocco

Across the Sahara to the west, thousands marched to demand the release of political prisoners held by Moroccan monarch Mohammed VI’s regime. These appeals, also made to the courts, were dismissed, prompting protester Nasser Zefzafi to sew his lips shut.

State repression of the skyrocketing dissatisfaction with the monarchy is plainly contradicting the narrative Mohammed VI has written for himself. Surely, he will no longer be considered a beacon of light in North Africa.

This moment in Morocco highlights the crucial relationship between popular narratives and political power—something movements can capitalize on.

Zimbabwe

Zimbabweans have earned a reputation for protesting in recent years, including this 2017 solidarity march to "tell Mugabe to go." Source: Flickr user Zimbabwean-eyes.

Zimbabwe has cultivated a reputation for protest in recent years. The new Emmerson Mnangagwa regime has arguably become even more iron-fisted than its predecessor Robert Mugabe, whose rule had begun with the country’s independence in 1980.

Recent torture, attacks, and killings of workers have only brought more Zimbabweans into the struggle for freedom. One protester rendered disabled by past torture led a march against abductions of medical sector unionists!

Economic demands are being politicized strategically by organizers and aim to appeal to a broad base of citizens as Mnangagwa attempts to justify his heavy hand. Unionists, especially teachers, have proven to the world that the spirit of African worker socialism is not dead.

Benin

Benin is historically more democratic and politically stable than most of its neighbors, but like many places on our planet, space to voice dissent is disappearing. Calls for President Patrice Talon to step down in June brought hundreds out for demonstrations, but not without state brutality in response.

Political protests surfacing in a country like Benin may offer an indicator that as authoritarianism normalizes, so should popular uprising.

Guinea

Guineans comprise the newest African population to join this year’s list of popular uprisings. Last month, protest leaders were charged and convicted for organizing against 81-year-old President Alpha Condé, who aims to amend the constitution to extend his rule.

Resistance in Conakry is still high as thousands are taking action to free their organizers from jail, and the mostly nonviolent mass protests have spilled over into November, with at least 14 deaths amid security force live fire.

The country of about 13 million affirms that the most effective response to repression is persistence and stronger resistance.

Centering Africa’s Resistance Knowledge

The above anecdotes do not include countless African movements against corruption, or for economic justice, cultural rights, and civil liberties that have dotted the continent this year, even in highly repressive contexts. More investment must be made across the diverse nations of Africa to better understand how we all—those living within and outside of Africa—can urgently strengthen our resistance to the worrying rise of autocracy.

Phil Wilmot

Phil Wilmot is a former ICNC Learning Initiatives Network Fellow, co-founder of Solidarity Uganda, and a member of the Global Social Movement Centre and Beautiful Trouble. Phil writes extensively on resistance movements and resides in East Africa. Write to Phil at phil@beautifultrouble.org.

Read More