Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Jacob LewisJune 24, 2021

Register for an ICNC webinar on Wednesday, June 30, 2021, featuring the author of this blog post: "How Social Trust Shapes Civil Resistance: Lessons from Africa."

For popular nonviolent campaigns to work, they must effectively mobilize both activists and bystanders while maintaining nonviolent discipline. In a world of diminishing social trust, this becomes exceptionally difficult. I address this challenge in my forthcoming ICNC research monograph, examining how trust shapes two important elements of civil resistance: mobilization and nonviolent action across Africa.

Why focus on this geographic region, when movements have been changing the political landscape all over the world for decades or longer? Africa is incontestably a hotbed of civil resistance; what’s more, it’s recently been the scene of several successful episodes of civil resistance—from Côte d’Ivoire and Uganda to Algeria and Sudan. Organized nonviolent movements have successfully challenged corrupt leaders and made progress toward democratic improvement and consolidation. The region is therefore fertile ground for pioneering research to better understand the role that trust plays in facilitating nonviolent actions.

How might higher levels of social trust facilitate civil resistance? In my forthcoming monograph, I argue that there are two important mechanisms at work.

National Women’s Day in South Africa marks the historic protest in 1956 of women against apartheid policies. Source: Spicyblackafrica.

Trust may alter the perceived costs of participation.

Civil resistance can be costly and activists are often subject to violent repression, so why would anyone risk taking to the streets? When people trust one another, they not only believe that others will show up to an event with them, but they also develop bonds of solidarity, mutual aid initiatives and moral community. In this light, high-trusting individuals and groups may actually feel the pains of not participating in a campaign more acutely than the risks of being involved in civil resistance.

Trust may be essential to remaining nonviolent in the face of violent repression.

Civil resistance works best when activists remain committed to nonviolent action. But when the chips are down and repression increases, it can be hard to remain committed to nonviolent discipline, as struggles in Syria or now in Myanmar can demonstrate. Trust may be a critical factor that keeps activists certain that their fellow activists will “hold the nonviolent line”—even when times get really tough.

The Atbara people during the Sudanese revolution, November 6, 2019. Source: Wikipedia/Abbasher.

To analyze the importance and role of trust in civil resistance struggles, I began by examining how different forms of social trust correlate with self-reported willingness to join a nonviolent protest or demonstration in Africa. This information was available through the Afrobarometer survey (my monograph details this and more on my methodology if you’re interested).

I found that individuals with high levels of trust in their acquaintances and in their co-nationals report significantly higher willingness to protest than individuals with lower levels of trust. These effects are strongest in countries that have active civil societies, such as Mali, South Africa, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe.

I then tested whether these self-reports of “potential mobilization” correspond with actual, observed protest. I found that countries with the highest levels of reported “potential mobilization” also observe the highest number of actual nonviolent protests.

Next, I examined whether different forms of social trust—in acquaintances, in co-nationals, and in diverse populations (simply put, people who are not like you)—influence a reduced justification for the use of violent political action. I found that all forms of social trust diminish significantly individual justifications of violent political action.

Lastly, I assessed whether social trust has bearing on lower levels of actual, observed violent contention—and I found that it does.

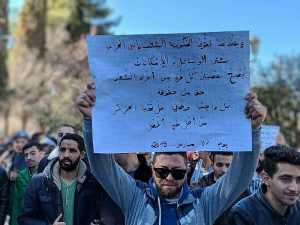

Demonstration against Bouteflika's 5th term, Algeria, March 1, 2019. Source: Wikipedia/Y-Drid.

What are the takeaways?

For scholars

For scholars interested in civil resistance, the monograph begins to unpack an important psychological dynamic of collective action by examining different forms of trust and how they correspond with willingness to mobilize, as well as preferences for nonviolent action. My monograph also suggests a number of important and interesting areas of future research. For example, what role do high-trusting individuals play in shaping the overall level of trust within a civil resistance organization? And does trust play an important role in whether civil resistance organizations can work together within the larger context of a civil resistance campaign?

For activists and civil society leaders

My research provides insight into the importance of developing broad, diverse campaigns rather than narrow, ethically-specific (“single cause”) campaigns. One of the forms of trust that my monograph tests is trust in diverse populations—namely, how much individuals trust others who are not like them. I find that individuals who report higher levels of trust in diverse populations are less likely to believe that violent political action is ever justified. It may be that diverse campaigns are more able to remain nonviolent in the face of government repression. One potential way to apply this takeaway would be to build (or encourage movements to build) campaigns around issues, rather than around identity groups. For example, labor unions and professional organizations might be able to coordinate across ethnic, religious, and/or linguistic cleavages.

For allies of nonviolent activists and movements

This monograph focuses primarily on individuals rather than campaigns. As civil resistance continues to grow as an important tool for challenging authoritarian regimes around the world, it will be increasingly important to understand the relationship between individuals, organizations, and the success of important campaigns. Whether coming together to protest the repression of political opposition in Uganda, working to ensure democratic transitions in Mali, or protecting voting rights in the United States, it is critical to understand how to foster trust within civil resistance organizations and campaigns to ensure that they can be effective at mobilizing additional participants as well as remaining nonviolent.

Jacob Lewis

Jacob Lewis is an Assistant Professor of Global Politics in the School of Politics, Philosophy, and Public Affairs at Washington State University. His research centers on conflict processes and political psychology in the African context. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Maryland and has worked extensively in the fields of international development and public policy.

Read More