Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Abdourahman Mohamed Guelleh, "TX" and Amber FrenchNovember 17, 2020

This article was translated from the original French (here) by Amber French.

“We are still on the 'long road to freedom' but our approach is to work backwards from a future projected victory. Fear will change sides…”

– Abdourahman Mohamed Guelleh

Abdourahman Mohamed Guelleh, a major figure in the pro-democracy movement in Djibouti, shed his fear years ago, making way for hope—confidence I would even say. Confidence that his country in East Africa will see the day when repression ends and democracy reigns.

Abdourahman embarked on self-study of the strategy of nonviolent action in a repressive climate. He had just served four years in prison for participating in an opposition coalition meeting for which he was serving as secretary general at the time. The prison sentence came after a government massacre of civilians in Buldhuqo, a suburb of Djibouti, on December 21, 2015, in the lead-up to the 2016 presidential election.

Simply by typing "how to bring down a dictatorship without violence” into a search engine, he discovered some key texts on nonviolent resistance that had been translated into French and made available free of charge on the websites of CANVAS, ICNC, and other educational organizations. This was all back in 2015-2018.

In just a few years hence, hundreds of books, articles, videos, and other media are now available in 70+ languages on the internet for nonviolent activists. Some are designed for "beginners," like Abdourahman was in 2016, and some are for more advanced activists. The obstacles for activists to become self-taught have therefore been reduced.

By interviewing Abdourahman for Minds of the Movement, I wanted to channel his experience to reveal for others how activists can also become self-taught on the subject of civil resistance, even in a context of very harsh repression.

______

In what context did the pro-democracy movement in Djibouti turn to nonviolent struggle?

The streets of Djibouti. Source: Flickr user cristina317 (CC BY 2.0, cropped).

Abdourahman: The Republic of Djibouti, a former French colony, is located in East Africa on the Red Sea, where much of international trade passes. Nestled in a turbulent region that has become a breeding ground for terrorism and authoritarianism, a neighbor of Ethiopia, Somalia, Eritrea and Yemen, the country enjoys a highly strategic position despite its 23,000 km2 and its population bordering on barely a million inhabitants concentrated in the capital. The great foreign powers, France, USA, China, etc. are jostling for influence there and have large military bases.

Only two presidents have succeeded at heading up the country since 1977. The first led it for 22 years (1977-1999). The second, Ismaïl Omar Guelleh, in power since 1999, is preparing to blow out of the water the longevity record of his predecessor with a fifth term after the elections next April.

A leaden blanket is systematically dropped over any discordant voice. The last massacre that killed dozens of innocent civilians took place on December 21, 2015, during a traditional and religious ceremony organized by local communities but forbidden by the regime.

No free voices can be expressed in the public media, which are reduced to a radio station, television channel, and newspaper, all controlled by the state. The voluntarily limited and overpriced internet speed is fueling the growth of social networks which, to the regime’s regret, remain an uncontrollable and inevitable time bomb.

Why were you drawn to nonviolent action as a method of opposing dictatorship?

For 43 years, the opposition attempted, unsuccessfully, armed struggle, ballot boxes, and boycotting elections. These strategies have never succeeded. Quite simply, the existing dictatorship holds power through repressive force and electoral fraud. Was Gene Sharp, in his book From Dictatorship to Democracy, not right in warning democracy lovers against authoritarian regimes?:

“Resistance, not negotiations, is essential for change in conflicts where fundamental issues are at stake. In nearly all cases, resistance must continue to drive dictators out of power. Success is most often determined not by negotiating a settlement but through the wise use of the most appropriate and powerful means of resistance available.”

Faced with the impossibility of defeating a dictatorship by the ballot box, rebellion or negotiation, the idea germinated in my mind of studying the strengths and weaknesses of nonviolent struggle to bring an end to the political conflict.

How did you decide to embark on self-learning of the strategy of nonviolent action?

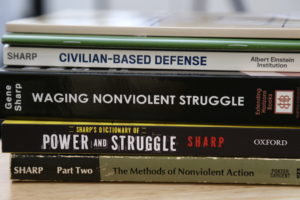

Source: ICNC.

Being in prison gave me time to reflect and ultimately inspired this self-learning journey. I was arbitrarily locked up following the massacre of December 21, 2015. Released from prison after four months of isolation, I then embarked on extensive research via the internet and the history of freedom fighters in the world, on techniques capable of bringing down a dictatorship without violence.

Meticulously organized and determined, I was not disappointed by what I learned and the time I spent conducting research on the internet about successful experiences around the world.

The books Blueprint for Revolution by Srdja Popovic; From Dictatorship to Democracy by Gene Sharp; and CANVAS’s 50 Crucial Points of Nonviolent Struggle were the texts that originally inspired me. These are the foundations of my learning. They are my companions at all times, my compass. This initial investment was not free, especially the internet access, but the books—either accessed online or ordered from distributors in Europe—at least did not represent a large cost. That being said, self-organization, drive, time, rigor, and energy were all required at this stage, as was a certain level of risk. I had a positive attitude about investing so much energy in the struggle for freedom and democracy in my country.

From 2016 to today, I have never tired of learning, virtually, from Gene Sharp about strategic issues, from Srdja Popovic about humor, and from Bob Helvey the essential issue of the pillars of the regime. Driven by the strategy of nonviolent action, I never tire from consulting documents, documentaries, films and books from ICNC and other sites. And with the intimate conviction, the immense determination to free the battered Djiboutian people, to establish a state of law and a democratic society. We are still on the 'long road to freedom' but our approach is to work backwards from a future projected victory. Fear will change sides.

How do you apply your knowledge to support the movement?

Our activists are encouraged by the photos, documentaries, films and stories told through the nonviolent revolutions of Serbia, Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, Sudan, Algeria, etc...

It was difficult for my colleagues at the beginning. As their leader, I explained to them, showed them the books, the films, the texts. Once I convinced them of the importance of nonviolent struggle, I organized a training of trainers. Today, it is the people I trained who in turn train the activists. And what made me very happy is that my teams believed in our new strategy and they have high hopes for victory.

How do you turn learning into action?

The great lesson I’ve learned from nonviolent action is to begin by testing very easy tactics—actions that everyone can talk about in town and that draw public interest. The initial actions you organize must be safe, easy to do and interesting for the activists involved.

____

Beyond the books cited by Abdourahman in this interview, we also recommend The Path of Most Resistance: A Step-by-Step Guide for Planning Nonviolent Campaigns by Ivan Marovic, designed specially for civil resistance beginners. The publication is also available in PDF in English, French, Spanish, and Catalan.

Abdourahman Mohamed Guelleh, “TX”

Abdourahman Mohamed Guelleh, “TX,” is the founding leader of Djibouti’s Rassemblement pour l’action, la démocratie et le développement écologique (RADDE, Rally for Action, Democracy and Ecological Development). The former mayor of Djibouti, TX abandoned politics in 2018 to advance Djibouti’s pro-democracy movement through grassroots organizing. He is an alum of the Solidarity 2020 and Beyond’s International Activists Convening, held in Kathmandu, Nepal in 2023.

Read More

Amber French

Amber French is Senior Editorial Advisor at ICNC, Managing Editor of the Minds of the Movement blog (est. June 2017) and Project Co-Lead of REACT (Research-in-Action) focusing on the power of activist writing. Currently based in Paris, France, she continues to develop thought leadership on civil resistance in French.

Read More