Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Mary Elizabeth KingApril 02, 2021

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the James Lawson Institute (JLI) this year manifested as a two-day public webinar on Monday, April 5 and Tuesday, April 6).

The Reverend James M. Lawson Jr. met the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. at Oberlin College, Ohio, in 1957, where King was lecturing. Lawson had been a conscientious objector and refused to fight in the Korean war, leading to imprisonment. The United Methodist Church approached the federal authorities and asked to be allowed instead to send Lawson as a furloughed missionary to India to teach. At the time Lawson met King, he had recently returned from three years as a coach at Hislop College in the Indian state of Maharashtra, where he was also campus minister. Lawson explained to King that he had decided while in college that he would become a Methodist minister and go South to dedicate himself to dismantling segregation and racism. Fascinated by Lawson's experiences in India, where he had known people who had worked alongside Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, King noticed that he and Lawson were both the same age, twenty-eight. He implored Lawson to come South immediately. “Don't wait! Come now! You're badly needed. We don't have anyone like you!”

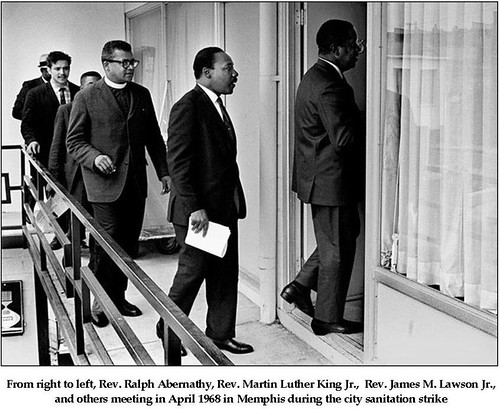

Source: pennstatenews (CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0, unedited).

By January 1958, Lawson was in residence in Nashville as the southern field secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). Associated with the International Fellowship of Reconciliation, FOR was a peace organization formed in response to the bloodshed of World War I in Switzerland, in 1914. The FOR affiliate in the United States, based in Nyack, New York, came into existence in 1915.

On arrival in Nashville, Lawson found that Glenn E. Smiley, a white, Texas-born Methodist minister and FOR’s national field director, who had served time in prison as a conscientious objector during World War II, had assembled a crammed schedule of workshops for Lawson to teach. After his initial seminar at the first annual meeting of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Columbia, South Carolina, King would put Lawson’s workshops on the program for every SCLC meeting as long as King lived.

Having previously arrived in India in 1952 (barely four years after Gandhi's assassination), based in Nagpur, at the crossroads of India, Lawson was knowledgeable about the Indian independence struggle. He had met and spoken with adherents who had worked directly with Gandhi, sometimes while visiting their sites of struggle. This allowed Lawson to become the critical agent—alongside Smiley and Bayard Rustin (field secretary for FOR and who later became known as the key organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom)—in interpreting the basics of Gandhian nonviolent action for both King and SCLC.

With links to a local movement that was organizing practice nonviolent demonstrations by 1958, Lawson was soon leading workshops for students who would eventually come from all of Nashville’s institutions of higher learning. These continued into the early 1960s and dovetailed with the student sit-in campaigns that swept across the Southland to desegregate public accommodations.

On April 1, 1960, Ella J. Baker, an esteemed theorist and figure in U.S. social history, convened the leaders of the various student sit-in drives at her alma mater Shaw University, in Raleigh, North Carolina. Three station wagons brought Lawson and the leadership group, headed by Diane Nash, from Nashville to the conference that would produce the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pron. snick). Nashville’s was the largest, most disciplined, and accomplished delegation at the conference. As 1960 ended, 70,000 students, mostly black, but increasingly joined by whites, had sat-in. Some 3,600 were arrested, most going limp in total noncooperation as police arrested them. Within a single year, 100 lunch counters had been desegregated in the mid-Atlantic southern states. These young teams of innovators, seasoned in nonviolent direct action, which essentially means taking the action straight to the source of the grievance, without working through representatives or agencies, were engines for organizing and change. Local movements were often catalyzed by the student sit-in campaigns. The Nashville group went on to mount a successful campaign to desegregate department stores and shops in downtown Nashville.

Lawson became the primary tutor concerning the theories and methods of nonviolent action for the two key organizations, SCLC and SNCC, in the Southern freedom movement’s wing of nonviolent direct action.

During the four years that I worked on the staff of SNCC, little was available in print to study. Lawson had some writings by Gandhi and also turned to the Bible and writings of the young Montgomery pastor Martin Luther King to plumb the depths of what it meant to take nonviolent action. Then, as now, planning, preparation, and practice was shared by word of mouth, whether in workshops or mass meetings in churches.

Rev. Lawson at a United for Peace and Justice march, April 4, 2009. Source: Fellowship of Reconciliation (CC BY-NC 2.0, unedited).

From 1958 on, Lawson has been guiding leaders, organizers, and agents of social change who want to prepare themselves for effective nonviolent direct action. During the intermittent decades, a volcanic explosion of research has altered the scarcity despite which he led the Nashville workshops. Today, basic works and case studies by foremost researchers and scholar practitioners are freely available for download in more than seventy languages ranging from the works of scholar Gene Sharp to those of the International Center for Nonviolent Conflict. Several online magazines freely share writings by engaged international scholars, leaders, organizers, and journalists. (See websites for the Albert Einstein Institution; the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict; Waging Nonviolence; and of course, the Minds of the Movement blog.)

The history of nonviolent action is rich, diverse, and dates to ancient times. Yet despite its historical and at times revolutionary significance over centuries and across continents, the academy with its universities, the news media, institutes of diplomacy and international relations, and policy makers have neglected the study of the social power and dynamics of civil resistance. In many societies, including the United States, the history of their wars is emphasized, while the successes of their nonviolent struggles are not taught to schoolchildren. Literally thousands of nonviolent struggles that have shaped the United States have not been studied or documented.

Even so, nonviolent transformation of conflict has been gaining respect among political analysts, politicians, peacemakers, and researchers. People power (the name bestowed from the 1986 collapse of the Marcos regime in the Philippines) has increasingly become recognized. Indeed, more than fifty dictatorships and tyrannies were collapsed or disintegrated in the same number of years, often by national mobilizations. These primarily democratic transitions resulted not from armed insurrections, but were due to carefully targeted political pressure from nonviolent direct action. Successful nonviolent campaigns and movements have also led ballot-box cleanup, fought for environmental preservation, secured civil rights, fought racism and prejudice, altered gender discrimination, secured codification of human rights, and lifted military occupations in countries such as Chile, East Germany, the Republic of Georgia, Poland, Serbia, and South Africa, to name a few. Number-crunching quantitative researchers offer persuasive findings that the most universal and widespread choice for groups that cannot redress their wrongs through the standard institutions of politics is now nonviolent civil resistance.

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the James Lawson Institute (JLI) this year is manifesting as a two-day public webinar on April 5 and 6 (register HERE). It was originally founded in 2012 by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, at the initiative of outgoing ICNC CEO Hardy Merriman, as a way to honor the Rev. Lawson. At JLI, we immerse ourselves in a carefully-honed program emphasizing history, theory, and practice. We have an undergirding conviction that history can be changed by exerting the social power possessed by citizens, and that this capacity is not the preserve of the nation-state, economic, and martial forces—instead, it is human agency. Equally important is an understanding by guiding thinkers and planners, along with popular appreciation, that any system requires popular obedience and cooperation, in order for it to persist.

Effective spokespersons must sometimes step ahead rapidly, unless the campaign must remain clandestine to survive. Nonviolent campaigns typically thrust forward the leaders who can exemplify and embody the mobilization and its cause. All of these factors are more important than the exact nature of the underlying fundamental grievances.

Mary Elizabeth King

Mary King is Director of the James Lawson Institute and a professor of peace and conflict studies at the UN-affiliated University for Peace. She is also a Distinguished Rothermere American Institute Fellow at the University of Oxford, Britain. Her work for the U.S. civil rights movement includes having served on the staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Read More