Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Lynette OngMay 17, 2022

Following two decades of large-scale nonviolent actions, Malaysia—the Southeast Asia nation known for a melting pot of multiculturalism—in 2018 overwhelmingly voted out the United Malays National Organization (UMNO) regime that had ruled the country for six decades. Despite UMNO’s comeback through backdoor channels two years after the historical election, the lessons that the nonviolent movement, Bersih (“Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections”), offer are not lost.

Today, the Bersih movement continues to be committed to democratization and clean elections in Malaysia. Bersih’s actions aim to induce political change not by empowering people to bring down the regime, but instead by improving the integrity of institutions so that the people can legitimately vote the government out of power.

In this blog post, I illustrate the contribution of this broad-based nonviolent movement in engineering electoral change, drawing upon my recently published book, The Street and the Ballot Box (Cambridge University Press, 2022). Malaysia’s experience offers important lessons for activists around the world aiming to produce a substantive impact on electoral outcome.

Emergence: From elite to grassroots movement

By 2011, in solidarity with the second rally held in Kuala Lumpur, Global Bersih organized peaceful assemblies in over 30 countries, including the United Kingdom (featured above). Credit: Jom Balik Undi Facebook page.

After a devastating electoral defeat in 2004, a group of opposition elites from the Chinese-dominated Democratic Action Party, the Malaysian Islamic Party, and the Justice Party came together to collaborate with 25 civil society organizations. They launched the Bersih movement. Thus at its inception, Bersih was an elite-initiated movement. The movement advocates for clean elections given prevalent vote-buying, phantom votes, and other dirty tricks the UMNO government frequently used to win elections. It also pushes for electoral reform that removes the unfair advantage that gerrymandering—redrawing electoral maps by the party in power—extends to the incumbents. Sparsely populated and conservative rural districts have consistently delivered electoral victories to the incumbents despite them losing support from the more educated urban electorates.

Framed broadly around clean and fair elections, Bersih is inclusive in its rhetoric and approach. In contrast to popular movements, such as the US-based Occupy Movement or LGBTQ+ movement that advance the rights of specific groups, Bersih champions the voting rights of all to the exclusion of none. Owing to its inclusiveness, its campaign for clean elections and its ability to raise voter turnout, the movement was able to canvas support across Malaysian society—from different social strata, ethnic and religious backgrounds. Despite the hope that the long-ruling regime will eventually be removed from power, change of government would not feature in Bersih’s lexicon until much later, in 2016, when public outrage exploded over a massive corruption scandal implicating then-Prime Minister, Najib Razak.

After organizing the first successful rally with 40,000 participants in 2007, the opposition elites handed the movement’s leadership to civil society leaders, rendering Bersih a grassroots movement from that point onward. Four subsequent Bersih rallies were held between 2011 and 2016. The rally size peaked at half a million participants at the "Bersih 4.0" rally in 2015, boosted by increasing unpopularity of the UMNO regime following the corruption scandal. Strong show of force at the Bersih rallies had a direct impact on boosting voter turnout in the subsequent federal parliamentary elections.

Diaspora engagement: The “imagined community”

Bersih community in Aberdeen, Scotland (photo taken in May 2013). Credit: Jom Balik Undi Facebook page.

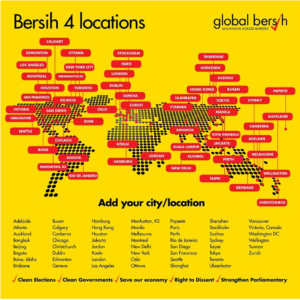

Bersih has adopted several innovative nonviolent tactics that help court participants. First, owing to brain drain, there are sizeable numbers of Malaysians working and residing in neighboring Singapore, and even in Australia, the United Kingdom and across the world. Bersih organizers had initially envisaged the movement to have a global presence. By 2011, in solidarity with the second rally held in the capital city Kuala Lumpur, Global Bersih organized peaceful assemblies in over 30 countries. This gave rise to what I call a global “imagined community” of people in yellow T-shirts advocating for free and fair elections in Malaysia!

CLICK TO ENLARGE. The list of cities where rallies were concurrently held in 2015. Source: Global Bersih.

A strong show of force globally serves more than symbolic purposes. The large Malaysian diaspora community, estimated at 1.4 million, holds sway in important swing electoral districts. Bersih launched a worldwide campaign in 2013 to educate overseas Malaysians about voter registration and voting fraud. Through adept use of social media, Bersih launched a highly successful campaign, “Jom Balik Undi” or Let’s Go Home to Vote, to encourage Malaysians to return home to cast their ballots. Supporters were encouraged to post their pictures and messages online.

The historical turnout of 83-85 percent in the 2013 and 2018 elections was no small feat, and it could not have been achieved without rallying efforts by Bersih. These efforts led directly to the UMNO coalition losing the popular vote for the first time ever in 2013, and subsequently losing the general election in 2018.

More “for” than “against”

Bersih stands apart from other popular movements worldwide because it strives to stay away from engaging in disruptive nonviolent tactics to gain traction, albeit using extra-institutional tactics. Instead, it has advocated for political change through strengthening institutions, human rights and electoral reform. To counter widespread voting fraud, Bersih calls for:

- Cleaning the electoral roll to eradicate “phantom voters”

- Reforming the postal ballot to ensure fairness and transparency

- The use of indelible ink to eliminate voter fraud

- A campaign period of minimum 21 days

- Free and fair access to media by opposition candidates

- Strengthening public institutions such as the judiciary, the Attorney General office, the anti-corruption agency, the police, and electoral commission to stop corruption and dirty politics.

Through Global Bersih, these messages to counter voting fraud were then spread to the “imagined community” of Malaysians around the world.

In other words, it is a movement that calls for political change not by empowering people to topple the government directly, but through strengthening practices and institutions that legitimately help people vote the government out of power.

Recent challenges and future directions

Two years after the historical election that ended UMNO’s rule, the opposition parties that brought Bersih to life and established a new government in 2018 were ousted through a backdoor deal. Several elected members of Parliament switched party allegiance, which allowed an interim government to form and ultimately the UMNO coalition to return to power. All these shenanigans took place during the Covid lockdown, which prevented the people from taking their political frustrations to the street. Malaysians have also been preoccupied with concerns of general economic livelihood under Covid more so than the day-to-day political bickering involving all parties.

Despite these challenges, Bersih is far from over. The movement played an instrumental role in a political campaign that successfully lowered the legal voting age from 21 to 18 in 2022. In a nation with a youth bulge that has rising aspirations, giving the youths a stronger voice bodes well for a more democratic future.

Bersih is also striving to get the Parliament to introduce a bill that prevents members of Parliament from hopping to different political parties—the very reason that brought down the elected democrats in 2020. Even if the democrats do not get elected to office any time soon, Bersih has left a legacy in Malaysian politics by promoting civic awareness of the right to vote and a sense of togetherness in a nation with multiracial and multicultural roots.

Lynette Ong

Lynette H. Ong is Professor of Political Science at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, the University of Toronto (Canada). She is the author of Outsourcing Repression: Everyday State Power in Contemporary China (Oxford University Press, 2022), and The Street and the Ballot Box: Interactions between Social Movements and Electoral Politics in Authoritarian Contexts (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Read More