Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Brian MartinJanuary 21, 2022

Read also: "What Soldiers and Police Need to Know About Protests (Series Part I)"

This blog post is also available in Thai here.

In my first post, I described the shades of grey that many police and security forces encounter when they show up to police a protest. I would like to follow up on that post here to provide some insight on what you can do. The first step is quite simple: You need to find out what’s actually happening.

Who are the actors in the protest?

Military commanders and police chiefs sometimes incorrectly assume that protesters are following orders or perhaps are being manipulated by hidden paymasters. However, usually no one has formal responsibility for giving orders because participation in nonviolent movements is voluntary and unpaid. Coordination without formal leaders is very different from the way official forces are organized, yet movements still get things done. Those attending voluntarily take up tasks such as helping the sick and injured, providing food and clothing, and setting up a rest area for breaks.

Although some nonviolent movements have had prominent leaders (Gandhi in India and Martin Luther King, Jr. in the United States come to mind), many movements favor a non-hierarchical structure. They want to organize their activities so that everyone has a chance to participate, to maximize inclusiveness—the main advantage that nonviolent movements have against, say, militias, which typically exclude women, children, and the elderly. To make decisions, nonviolent movements tend to use consensus processes that enable everyone, or nearly everyone, to agree.

You should assume that most protesters are there because they believe in a cause, not because they are being commanded to act.

What are my superiors telling me about the protest, and why?

Government and military leaders may be running their own agendas, serving their own interests and not the interests of the people. Government and military leaders may also be misinformed about what is actually going on, or deliberately attempt to mislead you about the nature of nonviolent action and the motives of people who are protesting.

So what’s really happening?

- See for yourself whether protesters are physically threatening anyone.

- Look for alternative sources of information to get a wider perspective.

- Talk to protesters or engage on social media to figure out what they are trying to achieve and how they’re going about it.

If you think your orders are reasonable, that’s fine. But what should you do if you think you’ve been ordered to do something illegal or unethical like harming peaceful protesters?

Kurdish demonstration against Turkey military action, The Hague, Netherlands, October 2019. Credit: The Left (CC BY-SA 2.0, unedited).

- Option 1. You can refuse. This might be risky. You could be subject to court-martial or worse. It is safest when others are also refusing.

- Option 1a. You can deal only with violent protesters (if there are any), even when you are ordered to act against nonthreatening ones.

- Option 2. You can pretend to obey. You are ordered to shoot, so you shoot but you miss.

- Option 3. You can pretend incapacity. You suddenly come down with a serious stomach problem.

- Option 4. You can pretend not to understand the orders. You show up at the wrong time, deal with the wrong group of people, and don’t act because you misheard the orders.

- Option 5. You can go missing. This is risky, because being absent without leave is a serious violation. This is safest when many others are doing the same thing.

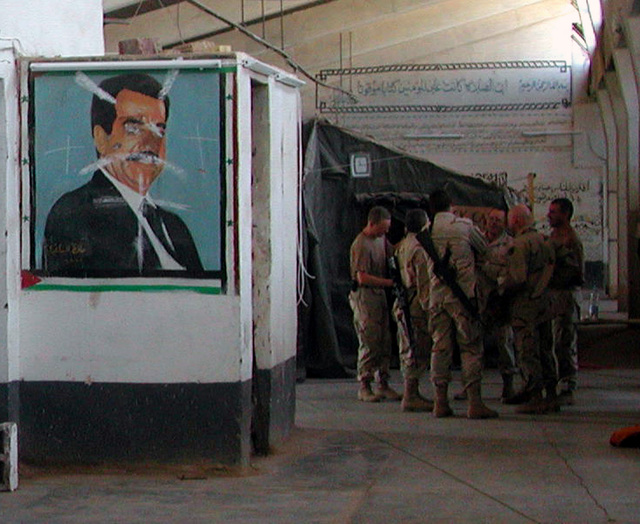

Photo credit: US Army soldiers confer near a defaced mural of Saddam Hussein at the Baghdad Central Detention Facility, formerly the Abu Ghraib Prison, in Baghdad, Iraq. (SUBSTANDARD)

When war crimes are exposed, who is blamed?

If bad things happen and they are exposed and investigated, only rank-and-file soldiers will be blamed. Political and military leaders are almost never held responsible.

In 2004, there was a worldwide exposé of the treatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. They were abused and tortured. Several U.S. soldiers went to trial. No commanders or policymakers faced the courts.

Can I support the protesters somehow?

What if you sympathize with the protesters and their goals? What can you do? There are various options, each with strengths and weaknesses.

In the famous novel The Good Soldier Svejk, a soldier in World War I hindered operations by pretending to be extremely stupid. When ordered to carry a letter to another commander, he later came back still holding the letter. When angrily asked why, he replied “You just said to take the letter, not to give it to him.”

- Quit your job and join the movement. This is noble but it might destroy your career, and you might become a target for attack. This option is safest when lots of others are doing the same thing.

- Talk to other soldiers and try to modify their views and behavior. In conversations, you can raise questions about what is happening in the protest and whether troops should be involved. Depending on the circumstances, you can be quite open about your views—if they are shared by many others—or quite cautious, so you seem loyal but just raising a few ideas. In this option, you are an inside fraternizer.Behavior is as important as viewpoints. What you do when on duty at a protest can influence others around you. By being calm and nonthreatening, you can ease tension. If you talk with protesters and laugh at their humorous stunts, you can set an example for other troops. Simply making light-hearted comments to your colleagues like, “Wait a second, I think I see my dentist in the crowd, don’t shoot” can make them think twice about engaging in potentially brutal behavior against peaceful protesters.

- Provide information to protesters. One way is to find a member of the movement whom you know and trust. Tell them what’s going on among the troops, such as what soldiers are being ordered to do, what they think about the situation, how morale is, and what nonviolent tactics are likely to be most effective. You don’t need to mention operational secrets. More important to protesters are insights into what will make their efforts more effective.You can meet face to face, by phone or email. You might want to take precautions to avoid being identified, such as using encryption or, if there’s an investigation, destroying your phone.Sometimes it can be difficult to find a member of the movement who will trust you. They might suspect you are an agent. So you need to figure out how you can establish your credibility.You need to be aware that some protesters may oppose any contact with the troops. On the other hand, some will greatly appreciate your advice.Essentially, you become a leaker. The great advantage of remaining in the force and anonymously providing information to the movement is that you can continue to do this as circumstances change.If you are really good at avoiding surveillance, you could even post comments online anonymously, giving advice to protesters from your perspective. However, this might lead to an attempt to track you down. Additional discussion of these and other options is also available in multiple languages here.

In summary

Nonviolent protesters seek to advance their cause without causing physical harm to anyone.

Nonviolent movements have internal disagreements. Among protesters, sometimes there are some who use violence, even though most oppose this. In other cases, those who use violence are opportunists who show up at the protest for their own purposes, or provocateurs who are trying to deliberately sabotage the movement.

If you attack peaceful protesters, you might actually strengthen the movement, because many people think it’s unfair to use violence against civilians.

If you want to support the movement, there are various options, depending on your circumstance and risk level.

Brian Martin

Brian Martin is Emeritus Professor of Social Sciences at the University of Wollongong, Australia. He has been researching nonviolent action since the late 1970s, with a special interest in strategies for social movements and tactics against injustice. He is the author of 21 books and over 200 articles on nonviolence, dissent, scientific controversies, democracy, education and other topics.

Read More