Presented by Isak Svensson on Thursday, October 17, 2019

Webinar Content:

Introduction of Speaker: 00:00 – 04:12

Presentation: 04:13 – 31:24

Questions and Answers: 31:25 – 1:00:29

Webinar Description:

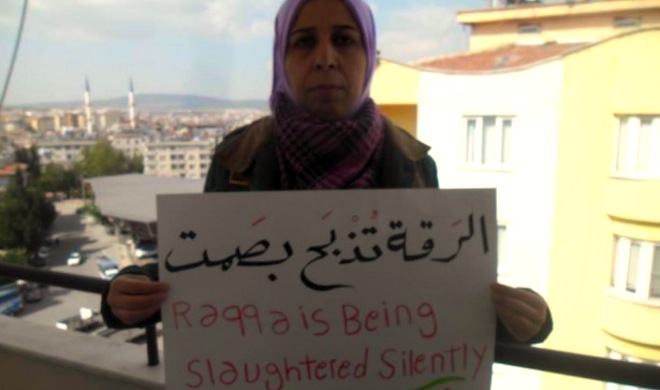

Suad Nofel, one of the leaders of the civil resistance movement against ISIS in Raqqa, Syria (WNV/Nofel).

In this webinar, we explored how people living in jihadist proto-states organized by groups like ISIS have used civil resistance —including acts of popular disobedience, non-cooperation, protests and public defiance—against such regimes to improve their lives and defend their values. These are situations where one might not expect civil resistance efforts to occur at all—when extremist, armed, and very violent Islamist rebel groups take control over a piece of territory, set up institutions resembling state-structures, and proclaim and enforce strict interpretations of sharia religious laws. Yet, important examples exist. In this webinar, we drew insights from empirical studies looking at experiences of civil resistance in Mali, Syria and Iraq (Mosul).

Presenter:

Isak Svensson is Professor at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, Sweden. His research focuses on religious dimensions of armed conflict, international mediation in civil wars, and dynamics of nonviolent civil resistance. He has authored or edited ten books and over 50 articles, book-chapters and books in international academic journals and presses, including Journal of Peace Research, Journal of Conflict Resolution, European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Cambridge University Press and Oxford University Press. He is project leader of the international research project ‘Resolving Jihadist Conflicts? Religion, Civil Wars and Prospects for Peace’, as well as for the research project ‘Battles without Bullets: Exploring Unarmed Conflicts’. Svensson has written several studies on nonviolent resistance, including on the structural factors that can help enable the onset of nonviolent uprisings (Butcher & Svensson 2016), political jujitsu (Sutton, Butcher & Svensson 2014), strategic substitution (Svensson & Lindgren 2013), the role of mediation in nonviolent uprisings (Svensson & Lundgren 2018), and ethnic cleavages in nonviolent uprisings (Svensson & Lindgren 2011). Currently, Svensson is working on a book project on civil resistance in the context of jihadist proto-states. To read more about Isak’s publications, click here.

Isak Svensson is Professor at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, Sweden. His research focuses on religious dimensions of armed conflict, international mediation in civil wars, and dynamics of nonviolent civil resistance. He has authored or edited ten books and over 50 articles, book-chapters and books in international academic journals and presses, including Journal of Peace Research, Journal of Conflict Resolution, European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Cambridge University Press and Oxford University Press. He is project leader of the international research project ‘Resolving Jihadist Conflicts? Religion, Civil Wars and Prospects for Peace’, as well as for the research project ‘Battles without Bullets: Exploring Unarmed Conflicts’. Svensson has written several studies on nonviolent resistance, including on the structural factors that can help enable the onset of nonviolent uprisings (Butcher & Svensson 2016), political jujitsu (Sutton, Butcher & Svensson 2014), strategic substitution (Svensson & Lindgren 2013), the role of mediation in nonviolent uprisings (Svensson & Lundgren 2018), and ethnic cleavages in nonviolent uprisings (Svensson & Lindgren 2011). Currently, Svensson is working on a book project on civil resistance in the context of jihadist proto-states. To read more about Isak’s publications, click here.

Relevant Webinar Readings:

Confronting the Caliphate (Working Paper) – Isak Svensson and Daniel Finnbogason

How Ordinary Iraqis Resisted the Islamic State – Isak Svensson, Jonathan Hall, Dino Krause and Eric Skoog

Can Political Struggle Against ISIL Succeed Where Violence Cannot? – Maciej Bartkowski

Nonviolent Strategies to Defeat Totalitarians such as ISIS – Maciej Bartkowski

Nonviolent Resistance Against the Mafia: Italy (Chapter from Curtailing Corruption: People Power for Accountability & Justice) – Shaazka Beyerle

The Power of Staying Put: Nonviolent Resistance Against Armed Groups in Colombia – Juan Masullo

ISIS: Nonviolent Resistance? – Eli McCarthy

Dissolving Terrorism at its Roots – Hardy Merriman & Jack DuVall

When Terrorists Govern: Protecting Civilians in Conflicts with State-Building Armed Groups – Mara Revkin

Civil Resistance vs. ISIS – Maria Stephan

Defeating ISIS Through Civil Resistance? – Maria Stephan

How to Stop Extremism Before it Starts – Maria Stephan & Shaazka Beyerle

Additional Q & A:

Does Isak have any insights into the relatively high levels of comparability of participation by men and women shown in the chart presented on actions? The levels of participation were noticeably close.

One of the main features of civil resistance campaigns is that they allow for a more broad-based participation than violent insurgencies. In the context of jihadist proto-states, civilians can engage in a diverse set of nonviolent actions, such as protests, not paying taxes, working slowly, or smoking. This variety increases the potential pool of participants, allowing for people with different levels of commitment and backgrounds to engage in civil resistance.

This can explain, to some extent, why we observe similar levels of participation in civil resistance by women and men in Mosul, despite the women facing more restrictions to access the public spaces under the rule of Islamic State. Relatively few participants engaged in public forms of resistance, being the display of anti-Islamic State slogans and banners the most common of these forms. Regarding actions of noncooperation, women avoided to pay taxes to Islamic State to a larger extent than men did, and there were no differences in regards to actions such as quitting the university (or taking their children out of school), or not going to work, which were the most prevalent in this category. In regards to everyday resistance, more men than women engaged in actions such as smoking or drinking alcohol, potentially showing cultural differences.

In sum, the results from the survey show that women and men participated to a similar extent in civil resistance against the rule of Islamic State, and it is likely that the wide set of alternatives available for civil resistance (beyond open, public actions) facilitated this similarity.

I wonder if you could expand on a case where a village has “locally” overthrown a jihadist proto-state by getting them to leave. Are there any such cases under ISIS in particular? What specific types of actions worked and why?

Civilians expelled a jihadist proto-state from their village in several cases. In our study on Syria, out of the 155 protests that demanded a jihadist group to leave their village, 13 of them were successful in forcing the group to abandon the area. That constitutes roughly 8% of them. Most of the successful cases targeted Hayaat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), with one case in which the Rahman Corps were forced to leave the territory.

For instance, in March 2015, about 1000 residents of Babella (Syria) demanded HTS to leave the area. Five days later, HTS reached an agreement with Ahrar al-Sham and Jaysh al-Islam and left. In another example, protesters in Atareb demanded HTS to leave the village in January 2017. The same day, after shooting at the protesters, HTS left the village. In September of 2017, about 400 residents in Kafr Batna demanded Jaysh al-Islam and Rahman Corps to leave the Ash’ari farms area, due to damage to crops. They were successful in making Rahman Corps to abandon the place the same day.

We did not find any case in which ISIS was driven out of a village through civil resistance. We are still in process of understanding the conditions that increase the likelihood of success of civil resistance in this context. For instance, it seems that previous repression by the jihadist proto-state increases the chances of success of the activists, supporting the ‘political jiu-jitsu’ explanation.

To what extent are jihadist groups responsive to civilian demands? and do they link these demands to their sustainability of governing?

Three concrete examples from our on-going research in Syria where the jihadist gave in to local protesters demand:

- In December 2018, in the northern Syrian province of Idlib, the al-Qaeda-associated rebel group Hayaat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)1 kidnapped a medical doctor. Informed about this incident, his colleagues reacted immediately. Within hours, doctors, nurses and medical staff across different hospitals and NGOs in the province went on a spontaneous strike and refused to carry out their duties. In response, HTS yielded to the demands, and a few hours later, decided to release the kidnapped doctor.

- On the 2 of March in Atareb, protesters demand HTS to leave the village of Jeineh, and on the same the HTS convoy withdrew.

- The protest campaign in the Maarat al-Numan have reached a number of outcomes in terms of making the jihadists to change their policies and withdraw.

Hence, in some cases, the jihadist rebel-rulers seem to accommodate the protesters’ demand. Overall, of the rate at which the local anti-jihadist protests in Syria, that we have coded, were successful was 7% (44 out of 624).

There is variation in terms of how jihadist groups try to adapt to the local demands and culture. For instance, the rule of Ansar Dine, AQIM (al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb), and MUJAO (Mouvement pour le Tawhîd et du Jihad en Afrique de l’Ouest) in Mali was perceived by the local population as alien, and protests took place against the imposition of a strict implementation of sharia law by these groups. This was also the case for Hayaat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in places such as Maarat al-Numan (Syria), whose rule was met with numerous forms of resistance by the civilians.

In the case of Islamic State in Mosul, interviews with refugees who escaped the rule of ISIS show that, initially, many residents in Mosul embraced ISIS fighters as an alternative to what they perceived as a sectarian Iraqi government (Wedeman 2016). However, this gradually changed as the ISIS governance set a priority in regulating the behavior of the populations in the areas it controlled, establishing an oppressive and punitive system based on legal foundations (Wedeman 2016, Revkin 2016).

A different case is, for example, the rule of AQAP (al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula) in al-Mukalla (Yemen), in 2015-2016. At their arrival to the city, al-Qaeda created civilian institutions, run by locals, to conduct everyday governance, while al-Qaeda remained in charge of the security, military operations and dispute resolution. To adapt to the local norms, they refrained from the strict application of sharia. They introduced measures such as religious courts, and a religious police force. However, AQAP was less strict in that they allowed women to stay outside after dark, interfered little with dress norms, did not force people to pray or pay a religious tax, and made no effort to ban smoking, music, or television.

I noticed from the presentation that everyday resistance is to have the highest participation rates compared to open public protest action and even noncooperation. Can you say more about what everyday resistance entails and to what extent can it achieve changes in jihadist rule?

Everyday resistance is a term coined by James Scott in his 1985 book “Weapons of the Weak”, and it refers to actions of resistance that take place within the daily, cotidian routines of people. In this low-key type of activism, the line between political activism and decision-making in the personal sphere is not always clear. In the context of a jihadist proto-state such as Islamic State, we identified 12 possible actions of everyday resistance. These are:

- attending funerals of IS victims,

- playing music instruments,

- not praying regularly,

- listening to nonreligious music,

- practicing forbidden sports,

- smoking/drinking alcohol,

- working slowly (shirking),

- delaying compliance with IS orders,

- shaving the beard (men),

- walking in public without a male company (women),

- attending beauty salons (women),

- not covering their face in public (women).

In these types of state-formation projects, disobeying the rulers’ dictates, even if done for nonpolitical reasons, can serve to undermine the legitimacy of the jihadist rule. However, it is hard to assess the impact of these subtle forms of resistance on the governance of the jihadist rulers. Future research could investigate more in detail how everyday resistance can weaken a regime and, more specifically, how this type of resistance can undermine the rule of jihadist proto-states.

1Over the course of the war, HTS has been known under different names, such as Jabhat al-Nusra or Al-Nusra Front, Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, or Jaysh al-Fateh. The latter was a joint coalition with other jihadist groups that existed until early 2017. For the sake of consistency, we refer to the group as Hayaat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) throughout this paper.