This live ICNC Academic Webinar took place on Thursday, May 12, 2016 at 12 p.m. EST

This live ICNC Academic Webinar took place on Thursday, May 12, 2016 at 12 p.m. EST

This special ICNC webinar discussion featured: Lucia Mendizabal from Guatemala, one of the leaders of #RenunciaYa; Alejandro Salas, Regional Director Americas, Transparency International; Shaazka Beyerle, author, Curtailing Corruption: People Power for Accountability and Justice; and moderated by Dr. Maciej Bartkowski, ICNC’s Senior Director.

Watch the webinar below:

Webinar content:

1. Introduction of the speakers: 00:00 – 01:27

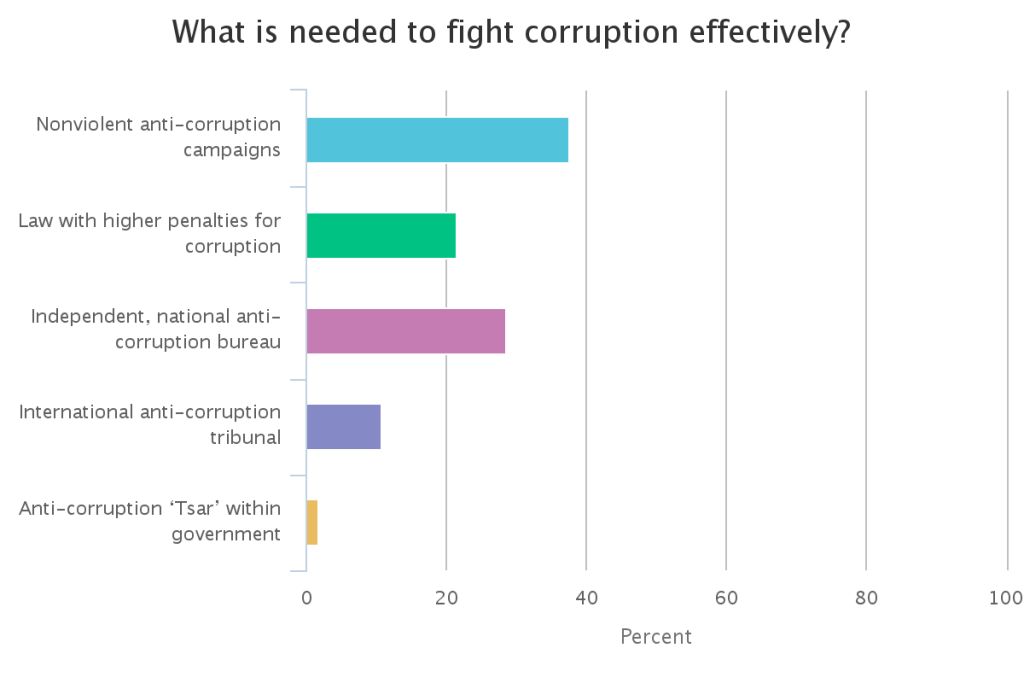

2. First Poll: 02:48 – 03:24

3. Moderator’s Introduction to the discussion: 03:30 – 05:55

4. Discussion: 05:57 – 46:30

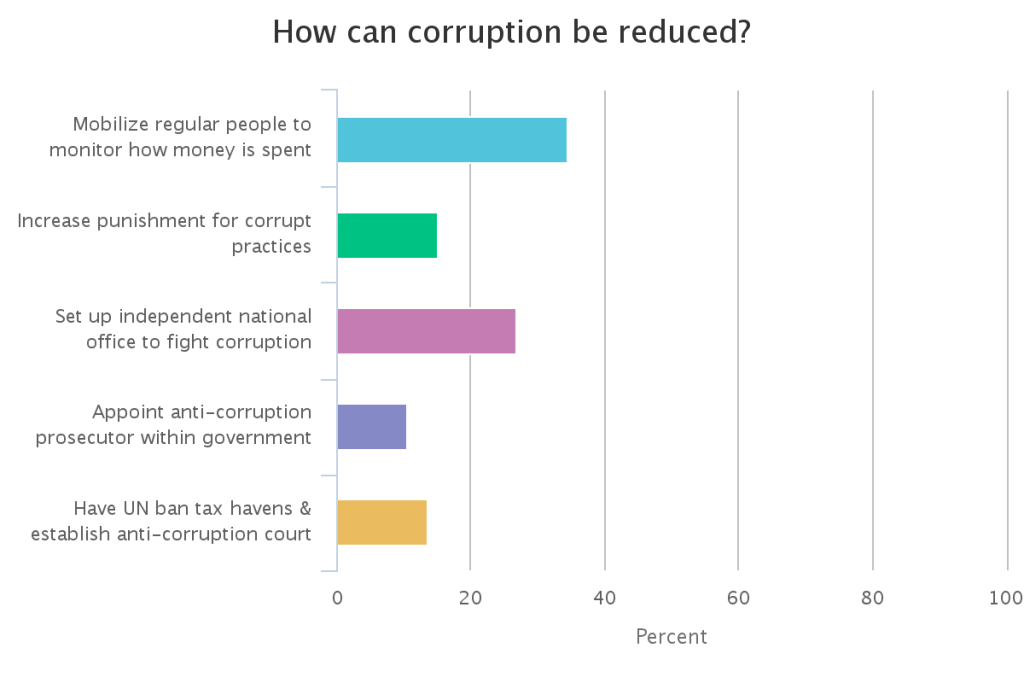

5. Second poll – 47:22 – 47:30

6. Questions and Answers: 47:34 – 1:17:19

Response to First Poll

These graphs show the results of the polling that was conducted during the webinar among the webinar participants. The first one was conducted at the beginning and the second one at the end of the webinar.

Response to Second Poll

Webinar Summary

The webinar will discuss the role and impact of popular civil resistance struggles against corruption, look into why and how people rise up against corruption and impunity, discuss successes and setbacks of civil resistance fight with graft and abuse and highlight the differences but also synergies between bottom-up and top-down efforts to undermine corruption.

The webinar discussion will also address the nonviolent people struggles against corruption in Latin America. Last September Guatemala captured international headlines for a nonviolent victory over corruption and impunity that forced the resignations of the cabinet ministers, Vice-president and the President. The struggle led by the grassroots #RenunciaYa movement began after the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) uncovered a massive fraud. Inspired by their Guatemalan neighbors, after an investigative journalist uncovered ruling party theft from the public health care system, thousands in Honduras rallied to demand the creation of an international anti-corruption body similar to the one in Guatemala. In Brazil, in the wake of the three-year Ficha Limpa (Clean Record) movement to clean up the Congress, an active citizenry has been targeting political corruption, elite impunity, and state mismanagement. At the same time, students in Paraguay mobilized over corruption and nepotism in universities (#PYnotecalles) and empowered communities to monitor local use of the country’s social investment fund.

Whether in democracies or nondemocracies people mobilize and resort to civil resistance to fight corruption and impunity. Similarly to the fight with unjust, repressive or undemocratic rule the nonviolent anti-corruption struggle is not risk free, as the assassinations of the Honduran indigenous, human rights and environmental leaders, Berta Cáceres and Nelson García attest to. The challenges for the anticorruption activists are great though thousands around the world remain determined to carry on their grassroots mobilization and fight.

This webinar will shine light on the brave women and men, their strategic acumen and nonviolent struggle for better, more accountable and transparent governance in their countries.

Further Participant Questions

Questions not addressed during the webinar recording itself.

Participant’s Question: How can civil resistance campaigns and movements tackle corruption during democratic transition or after the fall of a regime?

Alejandro Salas: This is a key moment where the efforts of civic movements against corruption can move from complaint and anger into a stage of proposing to set new rules of the game that can prevent corruption from happening again. Campaigns and movements need to join forces with relevant institutional and civic actors (among others, reform minded politicians, universities, think tanks and NGOs) that have already worked and designed reform proposals, or that have the capacities and resources to devise new law or oversight and control mechanisms. Depending on the specific country situation, one could push, for example, to have a multi-stakeholder commission that, after consultation with broader groups of population, can design a national anticorruption plan or a similar, broad based, commitment that will be adopted by the new authorities. This happened in Peru, for example, after the fall of the Fujimori regime in the year 2000 and the creation of the National Anticorruption Plan promoted by the Consejo Nacional Anticorrupción. Each country has its particular characteristics, but the idea is the same, continue the broad movement and the pressure it generates on elites to deliver while, at the same time, channel proposals for institutional change through multi-stakeholder bodies and engage the new authorities.

Lucia Mendizabal: During the civil movement of 2015 many groups, now referred to as collectives, arose. This splintering happened because there was no political organization behind the movement, and none of us had been in politics before. So we started to organize the collectives a little better, and from there, we started contacting each other in order to articulate. Most civilians are not well-versed in how their laws or government works, or how it is exactly that a chain of corruption can overcome the law and allow politicians to commit acts of corruption. Consequently, the next step was to get to know the laws and government’s structure. It is important that all collectives are connected and well organized, as corruption will not be stopped simply by overthrowing the heads. Corruption takes place across different levels of government and across all branches (executive, judicial and legislative), and there are additionally corruptors outside of the government that benefit from and contribute to government corruption. In order to tackle corruption, citizens must together become very aware and involved in supervising the actions of those in government, and regularly denouncing any deviations. In Guatemala, pressure from the masses has initiated a change in attitude from politicians, and an awareness of corruption.

Participant’s Question: In addition to increased access to information and greater financial transparency what are some of the other broader strategies to fight corruption that are pursued on different levels of governance: local, national or even translational, and what are the linkages between these strategies as well as campaigns that take place on different levels of governance? Any concrete examples to illustrate it?

Shaazka Beyerle: The right to information is considered a fundamental human right, and access to information flows from this right. Information alone may not be enough to counter corruption and bring forth change. Information combined with action (advocacy or civil resistance or both) can be more potent. When information is not readily available, asking questions and gathering information can be initial nonviolent actions, upon which other actions follow. This can include acquiring information about such things as government budgets, spending, parliaments, powerholder assets, and public services. Thus, tactics are sequenced. In the anti-corruption realm, the social audit is an example of such sequenced activities built on acquiring information. An example of civic actions at the international level took place recently in London prior to the Anti-Corruption Summit which ended on May 12 and was mentioned in the webinar. Information about bankers, real estate agents, accountants and lawyers providing services to launder ill-gotten gains, hide assets, dodge taxes was used as creative nonviolent tactics – “klepto-tours” and a bus tour pointing out the mansions and buildings I London bought with illicit funds. Both at the local and national level, monitoring is an activity that can impact corruption. In the civil resistance field, this can be considered a type of nonviolent tactic. If one goes back to the systemic definition of corruption presented in the webinar (see below), then we can see how monitoring is a tactic that can potentially disrupt a system of corruption. “[A] system of abuse of entrusted power for private, collective, or political gain – often involving a complex, intertwined set of relationships, some obvious, others hidden, with established vested interests, that can operate vertically within an institution or horizontally cut across political, economic and social spheres in a society or transnationally”

At the grass-roots, citizens have built campaigns and community initiatives around monitoring. The aforementioned social audit is an example. After acquiring particular forms of information, citizens use it to monitor schools and education services, reconstruction and social development programs, allocation of social investment funds, etc. Examples include Integrity Watch Afghanistan’s community monitoring initiatives, MUHURI (Muslims for Human Rights) and their 6-step social audits in Mombasa, Kenya, and the originators of this form of monitoring: the MKSS (Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan) and the “Right to Information” campaigns in India. In a rural region of Uganda, citizens “monitored” local police officers. They texted instances of extortion demands from police to a local civil society organization, which gathered this information and publicly presented it during weekly radio programs on corruption featuring an officer, who would also have to respond to calls from people in the communities. You can find more info about these cases in my book, Curtailing Corruption: People Power for Accountability and Justice. An excellent online documentary about MUHURI’s social audits can be found here.

At the national level, one can also find bottom-up monitoring campaigns and initiatives (also involving digital monitoring), e.g., the DHP* (Dejemos de Hacernos Pendejos) in Mexico and Mzalendo (patriot) in Kenya. In Paraguay, the reAcción youth initiative, , combines national and local by accessing information about FONACIDE (National Public Investment and Development Fund) to monitor its spending and programs in municipalities.

Presenters

Alejandro Salas is a Mexican political scientist, with extensive experience in the fields of governance, development and civil society. Throughout his career he has worked in the public sector, politics, research and civil society.

Alejandro Salas is a Mexican political scientist, with extensive experience in the fields of governance, development and civil society. Throughout his career he has worked in the public sector, politics, research and civil society.

As Transparency International’s Regional Director for the Americas, Alejandro leads the network of over 20 partner organisations from North, South and Central America as well as the Caribbean. Together with his team, he advises and support them in their efforts to fight corruption – from public awareness campaigns over research to legal activities. In addition, he manages the Americas related initiatives from the Secretariat in Germany.

Prior to Transparency International, Alejandro worked as a researcher and consultant at Instituto Apoyo, a think tank specialised in institutional reform and governance issues in Peru.

In Mexico, he worked in various areas of the Mexican public sector, including the Secretary of Social Development and the Senate of the Republic. He was also an advisor in the 1994 presidential campaign.

Alejandro holds a degree in Political Science from the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City and a Masters degree in Public Policy and Administration from the Institute of Social Studies in The Hague, Netherlands.

Lucía Mendizábal is a Guatemalan business entrepreneur. Although she had never been involved in politics in 2015, she was the one who posted a call online urging Guatemalans to go out and protest against government corruption. Thousands of citizens, in a country silenced by fear, went out and joined a peaceful movement that forced the resignation of President and Vice-president of Guatemala and their subsequent prosecutions on charges of corruption.

Lucía Mendizábal is a Guatemalan business entrepreneur. Although she had never been involved in politics in 2015, she was the one who posted a call online urging Guatemalans to go out and protest against government corruption. Thousands of citizens, in a country silenced by fear, went out and joined a peaceful movement that forced the resignation of President and Vice-president of Guatemala and their subsequent prosecutions on charges of corruption.

The Spanish language CNN named her one of “9 women that changed the world in 2015” alongside with Loretta Lynch, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Aung San Suu Kyi, Caitlyn Jenner, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Tu Youyou and Adele. Lucia is still involved in the citizen movement, working to achieve the goals that were put forward by the movement.

In her professional life, Lucia has experience in business strategy, sales, M&E of strategic plans, and finance, having worked in the banking, small and medium business administration, and real estate fields. Since 2012 she has been building a business in real estate that by now consists of over 250 realtors within the Entre Rios Real Estate network. She has been supporting EDUCCA Association against malnourishment since 2010, where she served on the board of directors.

Shaazka Beyerle is a researcher, writer and educator in people power and nonviolent action. She’s a Senior Advisor at the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, and a Nonresident Fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University.

Shaazka Beyerle is a researcher, writer and educator in people power and nonviolent action. She’s a Senior Advisor at the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, and a Nonresident Fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University.

She’s the author of, Curtailing Corruption: People Power for Accountability and Justice (Lynne Rienner 2014) and Freedom from Corruption: A Curriculum for People Power Movements, Campaigns and Civic Initiatives. She contributed a chapter on corruption and autocracy in, “Is Authoritarianism Staging a Comeback?” (Atlantic Council 2015); and co-authored articles on people power to impact global financial corruption in Diogènes, corruption and extremism in Foreign Policy, and civil resistance and the corruption-violence nexus in the Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare (Volume XXXIX, Issue 2, 6.2012). She wrote a chapter on corruption, conflict resolution and nonviolent action in, “Conflict Transformation: Essays on Methods of Nonviolence” (McFarland 2013). Ms. Beyerle also co-authored two chapters – on corruption and women’s rights – in, Civilian Jihad: Nonviolent Struggle, Democratization and Governance in the Middle East (Palgrave 2010). She has published in numerous outlets, including Al Hayat/Dar Al Hayat; Daily Star (Lebanon); European Affairs; Georgetown Journal of International Affairs; International Herald Tribune; Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare; openDemocracy; Peace and Conflict journal (forthcoming 2016); The Independent; and State Crime journal (forthcoming 2016).

Moderator

Dr. Maciej Bartkowski is Senior Director for Education & Research at ICNC. He works on academic programs for students, faculty, and educators to support teaching, research and study on civil resistance. He is a series editor of the ICNC Monographs. He holds an adjunct faculty position at Krieger School of Arts and Sciences of Johns Hopkins University where he teaches strategic nonviolent resistance.

Dr. Maciej Bartkowski is Senior Director for Education & Research at ICNC. He works on academic programs for students, faculty, and educators to support teaching, research and study on civil resistance. He is a series editor of the ICNC Monographs. He holds an adjunct faculty position at Krieger School of Arts and Sciences of Johns Hopkins University where he teaches strategic nonviolent resistance.

Dr. Bartkowski is a book editor of Recovering Nonviolent History. Civil Resistance in Liberation Struggles and Nation-Making published by Lynne Rienner in 2013. His recently authored and co-authored publications include:

- “Myopia of the Syrian Struggle and Key Lessons,” in Is Authoritarianism Staging a Comeback? Atlantic Council (2015), co-authored with Julia Taleb

- “Nonviolent Revolutions, Struggles for Political Recognition and Democratic Transition,” in Hallward and Norma, Understanding Nonviolence: Countours and Context, Polity Press (2015).

- Nonviolent Civilian Defense to Counter Russian Hybrid Warfare, Critical Policy Issue Study, Johns Hopkins Krieger School (2015). Review by Dr. Brian Martin.

His articles on civil resistance appeared in HuffingtonPost, Foreign Policy, Atlantic Council, War on the Rocks, openDemocracy, The Hill and other media outlets.

Recommended readings:

- Shaazka Beyerle, Curtailing Corruption. People Power for Accountability & Justice, (Boulder Co., Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2014), Chapter 4 (Ficha Limpa, Brazil), Chapter 10, DHP* Mexico) information here: www.curtailingcorruption.org

- Shaazka Beyerle, Freedom from Corruption: A Curriculum for People Power Movements, Campaigns and Civic Initiatives (2014), download free copy: http://www.curtailingcorruption.org/sites/default/files/Freedom-From-Corruption-Final-Edits-Aug-19-2015.pdf.

- Shaazka Beyerle, “Civil Resistance and the Corruption-Conflict Nexus”, Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, special issue on “Perspectives on Peace, Conflict and War,” (2011), Vol. 38, No. 2; case study on the Santa Lucia Cotzumalguapa community resistance against state capture and organized crime in Guatemala.

- Balcarcel, Pep, “Guatemalan Vice President Caught in the Eye of Corruption Storm,” Panama Post. April 21, 2015. Can be retrieved here: https://panampost.com/pep-balcarcel/2015/04/21/guatemalan-vice-president-caught-in-the-eye-of-corruption-storm/

- BBC Trending, “How a peaceful protest changed a violent country,” BBC. May 27, 2015. Can be retrieved here: http://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-32882520

- Malkin, Elizabeth, “Wave of Protests Spreads to Scandal-Weary Honduras and Guatemala,” The New York Times. June 12, 2015. Can be retrieved here: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/13/world/americas/corruption-scandals-driving-protests-in-guatemala-and-honduras.html?_r=0