Por: Ivan Marovic

Fecha de publicación: 2020

Descargar: Español | Inglés | Català | Portugués (Brasileño) | Francés | Urdu

Comprar una copia impresa

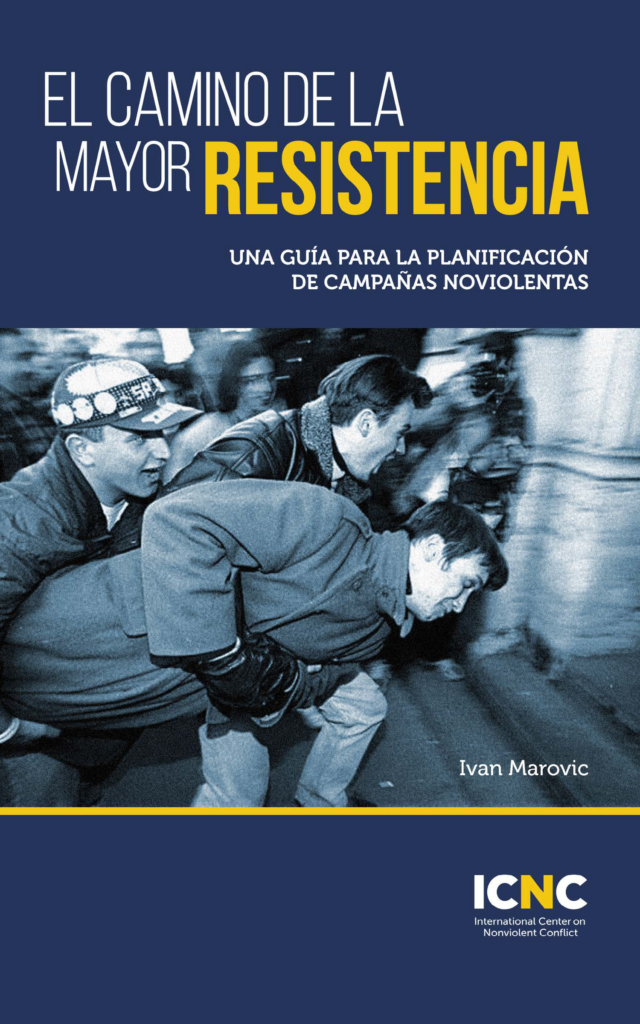

El camino de la mayor resistencia: Una guía para planificar Campañas noviolentas es una guía práctica para activistas y organizadores de todos los niveles que desean hacer crecer sus actividades de resistencia noviolenta en una Campaña más estratégica y de duración determinada. Es una guía para los lectores a través del proceso de planificación de la Campaña, dividiéndola en varios pasos y proporcionando herramientas y ejercicios para cada paso. Al terminar el libro, los lectores tendrán lo que necesitan para guiar a sus compañeros en el proceso de planificación de una Campaña. Se estima que este proceso, tal y como se describe en la guía, dura unas 12 horas de principio a fin.

El camino de la mayor resistencia: Una guía para planificar Campañas noviolentas es una guía práctica para activistas y organizadores de todos los niveles que desean hacer crecer sus actividades de resistencia noviolenta en una Campaña más estratégica y de duración determinada. Es una guía para los lectores a través del proceso de planificación de la Campaña, dividiéndola en varios pasos y proporcionando herramientas y ejercicios para cada paso. Al terminar el libro, los lectores tendrán lo que necesitan para guiar a sus compañeros en el proceso de planificación de una Campaña. Se estima que este proceso, tal y como se describe en la guía, dura unas 12 horas de principio a fin.

La guía está dividida en dos partes. La primera presenta y contextualiza las herramientas de planificación de Campañas y sus objetivos. También explica la lógica detrás de estas herramientas y cómo pueden ser modificadas para adaptarse mejor al contexto de un grupo en particular. La segunda parte proporciona planes de lecciones fácilmente reproducibles y compartibles para el uso de cada una de esas herramientas, y explora cómo integrar las herramientas en el más amplio proceso de planificación.

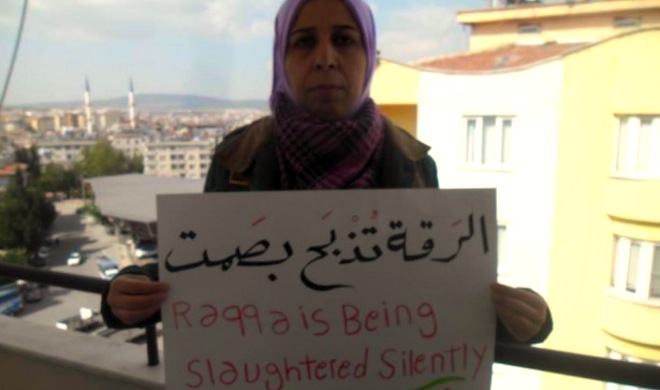

Isak Svensson is Professor at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, Sweden. His research focuses on religious dimensions of armed conflict, international mediation in civil wars, and dynamics of nonviolent civil resistance. He has authored or edited ten books and over 50 articles, book-chapters and books in international academic journals and presses, including Journal of Peace Research, Journal of Conflict Resolution, European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Cambridge University Press and Oxford University Press. He is project leader of the international research project ‘Resolving Jihadist Conflicts? Religion, Civil Wars and Prospects for Peace’, as well as for the research project ‘Battles without Bullets: Exploring Unarmed Conflicts’. Svensson has written several studies on nonviolent resistance, including on the structural factors that can help enable the onset of nonviolent uprisings (Butcher & Svensson 2016), political jujitsu (Sutton, Butcher & Svensson 2014), strategic substitution (Svensson & Lindgren 2013), the role of mediation in nonviolent uprisings (Svensson & Lundgren 2018), and ethnic cleavages in nonviolent uprisings (Svensson & Lindgren 2011). Currently, Svensson is working on a book project on civil resistance in the context of jihadist proto-states. To read more about Isak’s publications, click

Isak Svensson is Professor at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, Sweden. His research focuses on religious dimensions of armed conflict, international mediation in civil wars, and dynamics of nonviolent civil resistance. He has authored or edited ten books and over 50 articles, book-chapters and books in international academic journals and presses, including Journal of Peace Research, Journal of Conflict Resolution, European Journal of International Relations, International Negotiation, Cambridge University Press and Oxford University Press. He is project leader of the international research project ‘Resolving Jihadist Conflicts? Religion, Civil Wars and Prospects for Peace’, as well as for the research project ‘Battles without Bullets: Exploring Unarmed Conflicts’. Svensson has written several studies on nonviolent resistance, including on the structural factors that can help enable the onset of nonviolent uprisings (Butcher & Svensson 2016), political jujitsu (Sutton, Butcher & Svensson 2014), strategic substitution (Svensson & Lindgren 2013), the role of mediation in nonviolent uprisings (Svensson & Lundgren 2018), and ethnic cleavages in nonviolent uprisings (Svensson & Lindgren 2011). Currently, Svensson is working on a book project on civil resistance in the context of jihadist proto-states. To read more about Isak’s publications, click

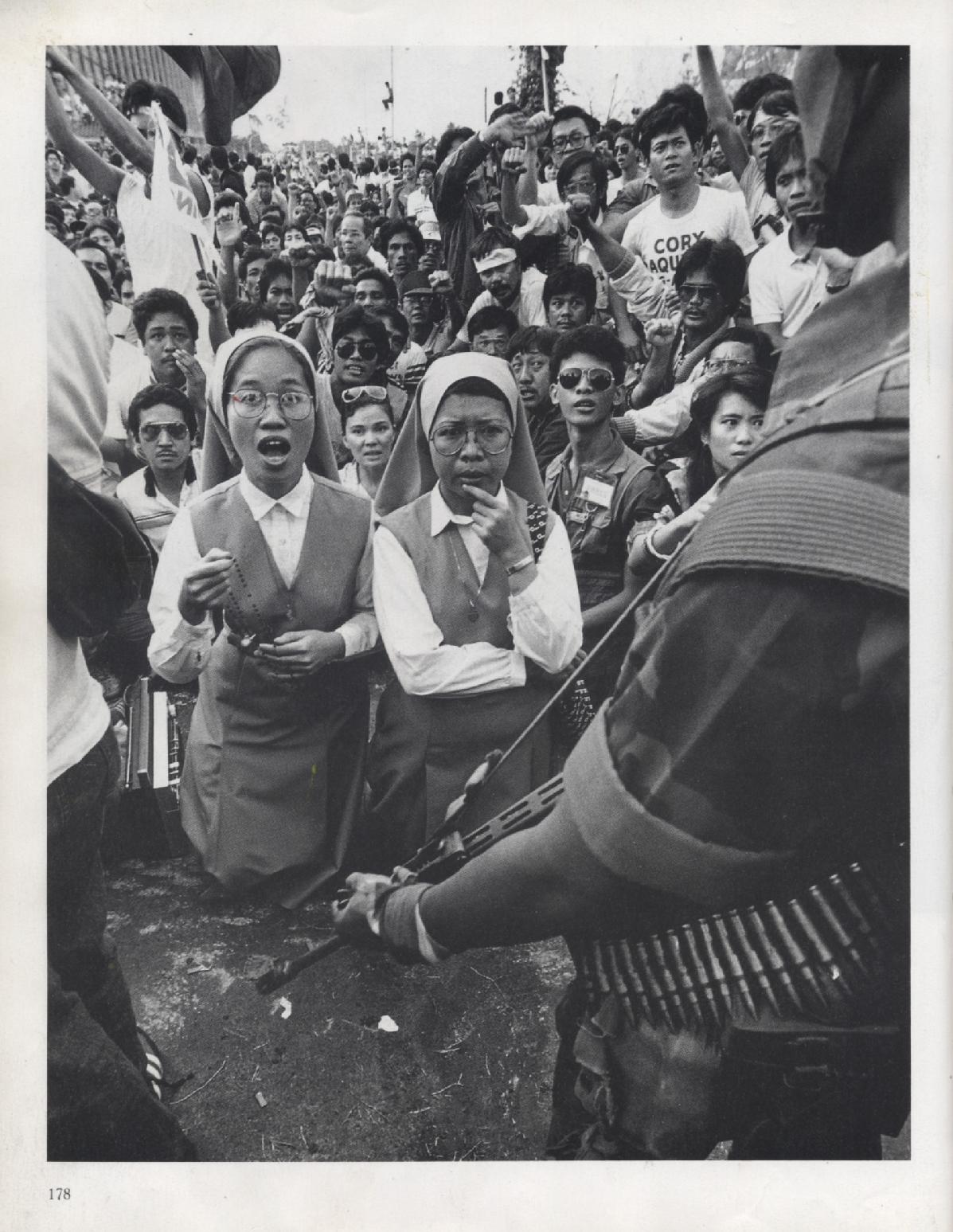

Marie Dennis serves on the executive committee of the Catholic Nonviolence Initiative, a project of Pax Christi International. She was on the Board of Pax Christi International for 20 years and served as co-president from 2007 to 2019. She is a Pax Christi USA Ambassador of Peace. Marie was director for 15 years of the Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns. She is author or co-author of seven books and editor of the award-winning Orbis Book, Choosing Peace: The Catholic Church Returns to Gospel Nonviolence. Marie was named person of the year by the National Catholic Reporter in 2016 and received honorary doctorates from Trinity Washington University and Alvernia University.

Marie Dennis serves on the executive committee of the Catholic Nonviolence Initiative, a project of Pax Christi International. She was on the Board of Pax Christi International for 20 years and served as co-president from 2007 to 2019. She is a Pax Christi USA Ambassador of Peace. Marie was director for 15 years of the Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns. She is author or co-author of seven books and editor of the award-winning Orbis Book, Choosing Peace: The Catholic Church Returns to Gospel Nonviolence. Marie was named person of the year by the National Catholic Reporter in 2016 and received honorary doctorates from Trinity Washington University and Alvernia University. Sharon Erickson Nepstad is Distinguished Professor of Sociology at the University of New Mexico. At UNM, she has served as both Chair of Sociology and as Director of Religious Studies. She has been a visiting fellow at Princeton University’s Center for the Study of Religion and at Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. She is the author of five books: Catholic Social Activism: Progressive Movements in the United States (2019, New York University Press), Nonviolent Struggle: Theories, Strategies, and Dynamics (2015, Oxford University Press), Nonviolent Revolutions: Civil Resistance in the Late 20th Century (2011, Oxford University Press), Religion and War Resistance in the Plowshares Movement (2008, Cambridge University Press), and Convictions of the Soul: Religion, Culture, and Agency in the Central America Solidarity Movement (2004, Oxford University Press).

Sharon Erickson Nepstad is Distinguished Professor of Sociology at the University of New Mexico. At UNM, she has served as both Chair of Sociology and as Director of Religious Studies. She has been a visiting fellow at Princeton University’s Center for the Study of Religion and at Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. She is the author of five books: Catholic Social Activism: Progressive Movements in the United States (2019, New York University Press), Nonviolent Struggle: Theories, Strategies, and Dynamics (2015, Oxford University Press), Nonviolent Revolutions: Civil Resistance in the Late 20th Century (2011, Oxford University Press), Religion and War Resistance in the Plowshares Movement (2008, Cambridge University Press), and Convictions of the Soul: Religion, Culture, and Agency in the Central America Solidarity Movement (2004, Oxford University Press).

Janel B. Galvanek is a Senior Project Manager at the Berghof Foundation and Director of Growing Tree Liberia, both based in Berlin, Germany. At the Berghof Foundation for 10 years, she is currently managing the Foundation’s projects in Somalia, which support mediation and reconciliation initiatives with local communities in the country. Janel’s professional focus includes engaging local actors and communities in peacebuilding and conflict transformation processes, as well as the interaction and coexistence between state-based conflict resolution mechanisms on one hand and community-based, traditional conflict resolution mechanisms on the other. She has done extensive research in Liberia on this topic as well as on the reintegration of former child combatants. In the past, Janel has also managed dialogue projects involving the High Peace Council and Ulema Council of Afghanistan. Janel’s work with Growing Tree Liberia supports the construction of a home designated for street children in Liberia and awards school scholarships for disadvantaged children in the downtown Monrovia area. She holds a Master’s degree in Peace Research and Security Policy from Hamburg University and an MA from Georgetown University in Washington, DC.

Janel B. Galvanek is a Senior Project Manager at the Berghof Foundation and Director of Growing Tree Liberia, both based in Berlin, Germany. At the Berghof Foundation for 10 years, she is currently managing the Foundation’s projects in Somalia, which support mediation and reconciliation initiatives with local communities in the country. Janel’s professional focus includes engaging local actors and communities in peacebuilding and conflict transformation processes, as well as the interaction and coexistence between state-based conflict resolution mechanisms on one hand and community-based, traditional conflict resolution mechanisms on the other. She has done extensive research in Liberia on this topic as well as on the reintegration of former child combatants. In the past, Janel has also managed dialogue projects involving the High Peace Council and Ulema Council of Afghanistan. Janel’s work with Growing Tree Liberia supports the construction of a home designated for street children in Liberia and awards school scholarships for disadvantaged children in the downtown Monrovia area. She holds a Master’s degree in Peace Research and Security Policy from Hamburg University and an MA from Georgetown University in Washington, DC. James Suah Shilue is the Executive Director of Platform for Dialogue and Peace (P4DP), a Liberian peacebuilding NGO involved in research and participatory action activities aimed at strengthening the capacities of state and non-state actors to prevent, manage and transform conflict through collaborative action. James also lectures at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Liberia. He has been serving as Executive Director for P4DP since June 2012. Prior to occupying this position, James served as Liberia Programme Coordinator for Interpeace and was responsible for the day-to-day management and overall direction of the programme. Mr. Shilue has been working on issues of development, research, Ebola, resilience, peacebuilding and conflict prevention, including land disputes and their resolution, for more than 15 years. In addition to overseeing the overall programme of Interpeace in Liberia, he has collaborated and provided consultancy services for various international projects, including the Geneva Graduate School Small Arms Survey, a Bentley University research project, the European Union Fragility and Resilience project, the USIP and George Washington University Rule of Law projects, the World Bank, the George Washington IDRC Liberian Diaspora Research project, the Carter Centre Urban Justice project and the International Center for Migration Policy Development. James has a Master’s Degree in Social and Community Studies (De Montfort University, UK) and an MA in Development Studies (Institute of Social Studies, The Hague). Mr. Shilue has extensive experience in the management of complex operations and uses this experience to hone his skills in facilitation, partnership development and peace research, including issues on human security, peace and reconciliation, and natural resource management.

James Suah Shilue is the Executive Director of Platform for Dialogue and Peace (P4DP), a Liberian peacebuilding NGO involved in research and participatory action activities aimed at strengthening the capacities of state and non-state actors to prevent, manage and transform conflict through collaborative action. James also lectures at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Liberia. He has been serving as Executive Director for P4DP since June 2012. Prior to occupying this position, James served as Liberia Programme Coordinator for Interpeace and was responsible for the day-to-day management and overall direction of the programme. Mr. Shilue has been working on issues of development, research, Ebola, resilience, peacebuilding and conflict prevention, including land disputes and their resolution, for more than 15 years. In addition to overseeing the overall programme of Interpeace in Liberia, he has collaborated and provided consultancy services for various international projects, including the Geneva Graduate School Small Arms Survey, a Bentley University research project, the European Union Fragility and Resilience project, the USIP and George Washington University Rule of Law projects, the World Bank, the George Washington IDRC Liberian Diaspora Research project, the Carter Centre Urban Justice project and the International Center for Migration Policy Development. James has a Master’s Degree in Social and Community Studies (De Montfort University, UK) and an MA in Development Studies (Institute of Social Studies, The Hague). Mr. Shilue has extensive experience in the management of complex operations and uses this experience to hone his skills in facilitation, partnership development and peace research, including issues on human security, peace and reconciliation, and natural resource management.

Ches Thurber is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Northern Illinois University whose research and teaching focus on international security, conflict, and governance. Dr. Thurber has held fellowships at the University of Chicago and the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard’s Kennedy School. He received his Ph.D. and M.A.L.D. from The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and his B.A. from Middlebury College. His book project, Between Gandhi and Mao: The Social Roots of Civil Resistance, investigates how social structures inform movements’ willingness to engage in nonviolent and violent strategies. Dr. Thurber’s research has been published or is forthcoming in the Journal of Global Security Studies; Conflict Management and Peace Science; and Small Wars and Insurgencies.

Ches Thurber is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Northern Illinois University whose research and teaching focus on international security, conflict, and governance. Dr. Thurber has held fellowships at the University of Chicago and the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard’s Kennedy School. He received his Ph.D. and M.A.L.D. from The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and his B.A. from Middlebury College. His book project, Between Gandhi and Mao: The Social Roots of Civil Resistance, investigates how social structures inform movements’ willingness to engage in nonviolent and violent strategies. Dr. Thurber’s research has been published or is forthcoming in the Journal of Global Security Studies; Conflict Management and Peace Science; and Small Wars and Insurgencies. Subindra Bogati is the Founder/Chief Executive of the Nepal Peacebuilding Initiative – an organization devoted to evidence based policy and action on peacebuilding and humanitarian issues. He has been working with conflict transformation and peace processes in Nepal through various national and international organizations for the last several years. Until recently, he was one of the principal investigators of the two year long research, dialogue and policy project on “Innovations in Peacebuilding,” which was a partnership between the University of Denver, Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) in Bergen, the Center for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation in South Africa and the Nepal Peacebuilding Initiative, Nepal. He holds an M.A. in International Relations from London Metropolitan University and was awarded the FCO Chevening Fellowship in 2009 by the Centre for Studies in Security and Diplomacy at the University of Birmingham. He is a Ph.D. candidate in the department of Political Science, Tribhuvan University, Nepal.

Subindra Bogati is the Founder/Chief Executive of the Nepal Peacebuilding Initiative – an organization devoted to evidence based policy and action on peacebuilding and humanitarian issues. He has been working with conflict transformation and peace processes in Nepal through various national and international organizations for the last several years. Until recently, he was one of the principal investigators of the two year long research, dialogue and policy project on “Innovations in Peacebuilding,” which was a partnership between the University of Denver, Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) in Bergen, the Center for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation in South Africa and the Nepal Peacebuilding Initiative, Nepal. He holds an M.A. in International Relations from London Metropolitan University and was awarded the FCO Chevening Fellowship in 2009 by the Centre for Studies in Security and Diplomacy at the University of Birmingham. He is a Ph.D. candidate in the department of Political Science, Tribhuvan University, Nepal.

Mohamed “Quscondy” Abdulshafi is a human rights activist and independent research consultant working with various organizations in peacebuilding and governance research. He’s a founding member of Darfur Student Movement, a student-led nonviolent movement against the genocide in Darfur. Quscondy is a winner of the Civil Society Leadership Award from the Open Society Foundations. Previously, he was a research fellow at Peace Direct. He was a founding staff the Sudan Democracy First Group, where he worked for several years in Kampala, Uganda. His research interests include inclusive peacebuilding, governance and youth participation.

Mohamed “Quscondy” Abdulshafi is a human rights activist and independent research consultant working with various organizations in peacebuilding and governance research. He’s a founding member of Darfur Student Movement, a student-led nonviolent movement against the genocide in Darfur. Quscondy is a winner of the Civil Society Leadership Award from the Open Society Foundations. Previously, he was a research fellow at Peace Direct. He was a founding staff the Sudan Democracy First Group, where he worked for several years in Kampala, Uganda. His research interests include inclusive peacebuilding, governance and youth participation. In this webinar, George Lakey, a long time social movement organizer and the author of

In this webinar, George Lakey, a long time social movement organizer and the author of  Activist: George Lakey’s first arrest was for a nonviolent civil rights sit-in in the 1960s. Since then, he has been active in a number of social movements and campaigns, including co-leading a sailing ship with medical aid to Vietnam in defiance of the U.S. war, campaigning with others in the LGBTQ community, organizing Men Against Patriarchy, and leading a statewide cross-race, cross-class coalition to fight back against Reagan. He has served as an unarmed bodyguard for human rights defenders in Sri Lanka, and recently walked 200 miles in a successful Quaker direct action campaign against mountaintop removal coal mining in Appalachia. In March 2018, he was arrested in the Power Local Green Jobs campaign demanding that the regional energy utility start a community solar program targeting poor neighborhoods.

Activist: George Lakey’s first arrest was for a nonviolent civil rights sit-in in the 1960s. Since then, he has been active in a number of social movements and campaigns, including co-leading a sailing ship with medical aid to Vietnam in defiance of the U.S. war, campaigning with others in the LGBTQ community, organizing Men Against Patriarchy, and leading a statewide cross-race, cross-class coalition to fight back against Reagan. He has served as an unarmed bodyguard for human rights defenders in Sri Lanka, and recently walked 200 miles in a successful Quaker direct action campaign against mountaintop removal coal mining in Appalachia. In March 2018, he was arrested in the Power Local Green Jobs campaign demanding that the regional energy utility start a community solar program targeting poor neighborhoods.

Ivan Marovic was one of leaders of Otpor, the student resistance movement that played a significant role in the overthrow of Serbian dictator Slobodan Milosevic on October 5, 2000. After the successful democratic transition in Serbia, Marovic began consulting with various pro-democracy movements around the world and became one of the leading thinkers and practitioners in the field of strategic nonviolent resistance

Ivan Marovic was one of leaders of Otpor, the student resistance movement that played a significant role in the overthrow of Serbian dictator Slobodan Milosevic on October 5, 2000. After the successful democratic transition in Serbia, Marovic began consulting with various pro-democracy movements around the world and became one of the leading thinkers and practitioners in the field of strategic nonviolent resistance